Table of Contents - Issue

Recent articles

-

Prevalence of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders among Primary Health Care Workers in Minna, Niger StateAuthor: Otojareri KADOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art001

Prevalence of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders among Primary Health Care Workers in Minna, Niger StateAuthor: Otojareri KADOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art001Prevalence of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders among Primary Health Care Workers in Minna, Niger State

Abstract:

Keywords: Work-related musculoskeletal disorders, Low back pain, prevalence, Healthcare worker, clinicians, primary health care centers, Minna metropolis, Niger State.Prevalence of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders among Primary Health Care Workers in Minna, Niger State

References:

[1] Yassi A. (2000). Work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 12(2):124-30. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200003000-00006.

[2] Punnett L, Wegman DH. (2004). Work-related musculoskeletal disorders: epidemiologic evidence and the debate. J Electromyography and Kinesio. 14:13-23.

[3] Korhan O, Memon AA. (2019). Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders. London: IntechOpen.

[4] Bernard BP. (1997). Musculoskeletal Disorders and Workplace Factors. A Critical Review of Epidemiologic Evidence for Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders of the Neck, Upper Extremity, and Low Back. US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Cincinnati. https://doi.org/10.26616/nioshpub97141.

[5] Smith DR, Leggat PA. (2003). Musculoskeletal disorders in nursing. Australian Nursing Journal. 11:1-4.

[6] Mark, G and Smith, A. (2011). Occupational Stress, Job characteristics, Coping & Mental Health of Nurse Practitioners. Journal of Health Psychology.

[7] Yasobant S, Rajkumar P. (2014). Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among health care professionals: A cross-sectional assessment of risk factors in a tertiary hospital, India. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 18(2):75-81. doi.org/10.1177/096032718900800518.

[8] Silverstein B, Clark R. (2004). Interventions to reduce work-related musculoskeletal disorders. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 4:135-52.

[9] Ries JD. (2018). Rehabilitation for individuals with dementia: facilitating success. Curr Geriatr Rep. 7(11):59–70. doi:10.1007/s13670-018-0237-1.

[10] Ergan M, Başkurt F, Başkurt Z. (2017). The examination of work-related musculoskeletal discomforts and risk factors in veterinarians. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol. 68:198-205. https://doi.org/10.1515/aiht-2017-68-3011.

[11] Rozenfeld V, Ribak J, Danziger J, Tsamir J, Carmeli E. (2009). Prevalence, risk factors and preventive strategies in work-related musculoskeletal disorders among Israeli physical therapists. Physiother Res Int. 15(3):176-84.

[12] Spector JT, Adams D, Silverstein B, (2011). Burden of work-related knee disorders in Washington State, 1999 to 2007. J Occup Environ Med. 53(5):537-547. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e31821576ff.

[13] Thomsom, M., Dipsych, B., Mappsych, S. (2006). Psychological determinants of Occupational burnout. Stress medicine, 8(3):151-159.

[14] Ayanniyi O, Lasisi OT, Adegoke BOA, Oni-Orisan MO. (2007) Management of Low Back Pain: - attitudes and treatment preferences of physiotherapists in Nigeria. Afri J. Biomed Res.10:41-49. doi:10.4314/ajbr.v10i1.48970.

[15] Sharma R, Singh R. (2014). Work-related musculoskeletal disorders, job stressors and gender responses in foundry industry. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 20(2):363-373. doi:10.1080/ 10803548.2014.11077053.

[16] Adegoke BO, Akodu AK, Oyeyemi AL. (2008). Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among Nigerian Physiotherapists. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 9:112. https://doi.org/10.1186/ 1471-2474-9-112.

[17] WHO Scientific Group on the Burden of Musculoskeletal Conditions at the Start of the New Millennium. (2003). The burden of musculoskeletal conditions at the start of the new millennium. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 919: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ 14679827. Accessed July 16, 2022.

[18] Downie R.S., Fyfe C., Tannahill A. (1990). Health Promotion Models and Values. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications.

[19] World Health Organization (1978). Primary Health Care: Report of the International Conference on Primary Health Care. Geneva: WHO.

[20] Otaru E.O. And Abubakar A.S. (2019). Geospatial Analysis of Primary Healthcare Facilities in Periurban Area of Minna, Niger State, Nigeria. African Scholar Journal of Env. Design & Construction Mgt. 15(4).

[21] Adeyemo, D.O. (2005): Local government and health care delivery in Nigeria in J. Hum Ecol. 149- 160.

[22] Eguagie, I and Okosun, V. (2010). The role of primary health care in Nigeria. Health care delivery systems: problems and prospects. 21:1.

[23] Sprinter, M. K. (2018). Geography of Minna, Published, Abomed Printers, ISBN: 123136723.

[24] Andersson K, Karlehagen S, Jonsson B, (1987). The importance of variations in questionnaire administration, Appl Ergon, 1987, vol. 18 (pg. 229-232).

[25] Kuorinka I, Jonsson B, Kilbom A, et al, (1987). Standardized Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms, Appl Ergon,18:(pg. 233-237).

[26] Awosan KJ, Yikawe SS, Oche OM, Oboirien M. (2017). Prevalence, perception, and correlates of low back pain among healthcare workers in tertiary health institutions in Sokoto, Nigeria. Ghana Med J. 51(4):164-174 doi:10.4314/GMJ.V51I4.4.

[27] American Psychiatric Association, (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

(5th ed.). Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association.[28] Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al, (2007). Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: A joint clinical practice guideline from the American college of physicians and the American pain society. Ann Intern Med. 2007; 147:478-491. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00006.

[29] Cho HY, Kim EH, Kim J, (2014). Effects of the core exercise program on pain and active range of motion in patients with chronic low back pain. J Phys Ther Sci. 26(8):1237-40. doi:10.1589/jpts.26.1237.

[30] Fransen K, Cruwys T, Haslam C, et al, (2022). Leading the way together: a cluster randomised controlled trial of the 5r shared leadership program in older adult walking groups. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 19(1):63. doi:10.1186/s12966-022-01297.

Viewed PDF 911 51 -

Assessment of the Impact of Caregivers Complementary Feeding Knowledge on Undernutrition among Children 6 to 36 Months in Borno State, NigeriaAuthor: Nyeapa YakubuDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art002

Assessment of the Impact of Caregivers Complementary Feeding Knowledge on Undernutrition among Children 6 to 36 Months in Borno State, NigeriaAuthor: Nyeapa YakubuDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art002Assessment of the Impact of Caregivers Complementary Feeding Knowledge on Undernutrition among Children 6 to 36 Months in Borno State, Nigeria

Abstract:

This paper is an assessment of the impact of Caregivers complementary feeding Knowledge on undernutrition among children 6-36 Months in Borno state. Large-scale renewables raise new challenges and provide new opportunities across Health systems. The paper considers the barriers faced by health workers and caregivers in Maiduguri Metropolitan Council in providing nutritional services to infants. We review the current state of knowledge in relation to nutrition. This paper then explores key issues in health and nutrition system structure, the main challenges to the uptake of renewables, and the various existing fiscal and policy approaches to encouraging health services. We also highlight possible ways of moving forward to ensure more widespread health management systems.

Keywords: Caregivers, Feed Knowledge. Maiduguri Metropolitan Council, Undernutrition.Assessment of the Impact of Caregivers Complementary Feeding Knowledge on Undernutrition among Children 6 to 36 Months in Borno State, Nigeria

References:

[1] WHO/UNICEF, 2003. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. Geneva: WHO/UNICEF.

[2] Fewtrell M., Bronsky J., Campoy C., Domellöf M., Embleton N., Fidler Mis N., Hojsak I., Hulst J.M., Indrio F., Lapillonne A., et al. Complementary feeding: A position paper by the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Committee on nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017; 64:119–132. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001454. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28027215/, and https://journals.lww.com/jpgn/fulltext/2017/01000/complementary_feeding__a_position_paper_by_the.21.aspx.

[3] Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition Feeding in the First Year of Life. [(accessed on 23 April 2020)];2018 Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/feeding-in-the-first-year-of-life-sacn-report.

[4] United States Department of Agriculture Timing of Introduction of Complementary Foods and Beverage and Developmental Milestones: A Systematic Review. [(accessed on 23 April 2020)]; Available online: https://nesr.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2019-04/Timing%20of%20CFB-Developmental%20Milestones-NE..._0.pdf.

[5] DiMaggio D.M., Cox A., Porto A.F. Updates in infant nutrition. Pediatr. Rev. 2017; 38:449–462. doi: 10.1542/pir.2016-0239. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28972048/, and https://publications.aap.org/pediatricsinreview/article-abstract/38/10/449/32000/Updates-in-Infant-Nutrition?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

[6] Black RE, Victoria CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, De Onis M, Ezzati M, Grantham S, Katz J, Martorell R and Uauy R; 2013. Maternal and Child Nutrition and Underweight in Low.

[7] Bakalemwa, R., 2014. Association between malnutrition and feeding practice among children aged six to twenty-four months at Mbagathi District Hospital Kenya. A dissertation submitted to the University of Nairobi.

[8] Hainkens G.T., 2008. Case management HIV infected severe malnourished children: challenges in the area with highest prevalence. The Lancet, 2008, Vol. 371, pp. 13051307.

[9] De Onis, M, Frongillo, E.A. and Blossner, M.I., 2000. Malnutrition Declining? An analysis is in Levels of Child Malnutrition Since 1980. Geneva: Word Health Organization.

[10] National Department of Health 2005: Directorate Nutrition. the integrated nutritional progaramme; nutritional satus. Johannesburg, South Africa.

[11] UNICEF, 2013. The Conceptual Framework on Maternal and Child Nutrition.

[12] Bégin F, Aguayo VM (2017) First foods: Why improving young children's diets matter. Maternal and child nutrition, 13(S2).

[13] Frankenberg E, Buttenheim A, Sikoki B, Suriastini W, (2009) Do women increase their use of reproductive health care when it becomes more available? Evidence from Indonesia. Studies in Family Planning, 40: 27-38.

[14] Bhalotra S, Karlsson M, Nilsson T, (2017) Infant health and longevity: Evidence from a historical intervention in Sweden. JEEA 15: 1101-1157.

[15] Lazuka V (2017) The lasting health and income effects of public health formation in Sweden (No. 153). Department of Economic History, Lund University.

[16] Hjort J, Sølvsten M, Wüst M (2017) Universal investment in infants and long-run health: Evidence from Denmark's 1937 home visiting program. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 9: 78-104.

[17] Jama NA, Wilford A, Masango Z, Haskins L, Coutsoudis A, et al. (2017) Enablers and barriers to success among mothers planning to exclusively breastfeed for six months: a qualitative prospective cohort study in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int Breastfeed J 1:12-43.

[18] Samuel FO, Olaolorun FM, Adeniyi JD (2016) A training intervention on child feeding among primary healthcare workers in Ibadan Municipality. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 8:81-86.

[19] Saleem AF, Mahmud S, Baig-Ansari N, Zaidi AK (2014). Impact of maternal education about complementary feeding on their infants' nutritional outcomes in low-and middle-income households: a community-based randomized interventional study in Karachi, Pakistan. J Health Popul Nutr 32: 623.

[20] Inayati DA, Scherbaum V, Purwestri RC, Wirawan NN, Suryantan J, et al. (2012) Improved nutrition knowledge and practice through intensive nutrition education: a study among caregivers of mildly wasted children on Nias Island, Indonesia. Food and nutrition bulletin, 33: 117-127.

[21] Imdad A, Yakoob MY, Bhutta ZA (2011) Impact of maternal education about complementary feeding and provision of complementary foods on child growth in developing countries. BMC public health 11(S25).

[22] Christiana, N-A., 2018.Gaps in knowledge levels of Health Workers on recommended Child feeding practices and Growth Monitoring and Promotion Actions. 2018.

Ivankova, N.V., Cresswell, J. W. & Stick, S. L 2006. Using Mixed Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice. Sage Publications, 18(3) 3 - 11. Doi:10.1177/1525822X05282260.Viewed PDF 996 37 -

Assessing Self-Care Practises of People Living With HIV/AIDS Attending the Antiretroviral Clinic of the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital, NigeriaAuthor: Opeyemi AdebayoDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art003

Assessing Self-Care Practises of People Living With HIV/AIDS Attending the Antiretroviral Clinic of the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital, NigeriaAuthor: Opeyemi AdebayoDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art003Assessing Self-Care Practises of People Living With HIV/AIDS Attending the Antiretroviral Clinic of the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital, Nigeria

Abstract:

In pursuance of the Global and National Goals of achieving HIV-AIDS epidemic control, it’s imperative to explore the Promotion of self-care management among people living with HIV/AIDS. Self-care management involves adhering to treatment regimens, good dietary patterns, increased physical exercise, social support, and health-seeking behaviours. The study reviewed five core pillars of self-care management: physical, psychological, emotional, spiritual, and workplace/professional. A cross-sectional descriptive, analytical study with a quantitative approach was conducted at the Antiretroviral Clinic of the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital from October to December 2020. Using random sampling, 372 people living with AIDS participated in the study. Trained research assistants collected data through a structured questionnaire administered at the antiretroviral clinic. The data was analysed using SPSS version 25.0, employing frequencies, computations, percentages, averages, means, standard deviation, and correlations, with a confidence interval of 95%. The study’s findings indicate that the weighted matrix scores (WMS) for various aspects of self-care were significantly above average, suggesting that PLHIV attending the antiretroviral clinic at the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital exhibit good self-care practices. However, psychological and workplace self-care requires some strengthening. The study revealed differences between self-reported appointment adherence and the calculated average appointment gap (3 visits). Associations were found between the average appointment gap and viral load among participants. The study did not establish any significant association between Total Matrixed self-care scores, adherence (appointment gap), or viral load suppression. The COVID epidemic and the nationwide ENDSARS protest in Nigeria during the study period were significant confounders and limitations.

Keywords: Antiretroviral drugs, appointment adherence, HIV/AIDS, psychological health, self-care management.Assessing Self-Care Practises of People Living With HIV/AIDS Attending the Antiretroviral Clinic of the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital, Nigeria

References:

[1] HIV/AIDS. (n.d.). Retrieved April 19, 2021, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids.

[2] WHO | What do we mean by self-care? (2019). WHO.

[3] National AIDS and STI’s Control Programme Federal Ministry of Health. (2016). National Guidelines for HIV Prevention, Treatment and Care 2016 (C. and S. N.-L. E. Dr. Emeka Asadu (Head Treatment, Dr. Chukwuma Anyaike (Head Prevention NASCP), Dr. Isaac Elon (WHO Consultant for the Guidelines Review), Dr. Justus Jiboye (Senior Programme Manager CHAI), Dr. Solomon Odafe (Senior Programme Specialist CDC), Dr. Ikechukwu Amamilo, (Programme Officer CHAI), & Dr. Daniel Adeyinka (Focal Person Paediatric ART NASCP) (Eds.)). Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja, Nigeria. https://aidsfree.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2016_nigeria_natl_guidelines_hiv_treat_prev.pdf.

[4] Deshpande, A. K., Jadhav, S. K., & Bandivdekar, A. H. (2011). Possible transmission of HIV Infection due to human bite. AIDS Research and Therapy, 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-6405-8-16.

[5] Aids, N. (2018). Rapid_Advice_Art. 1–28. papers://a4f304c0-1221-416b-a5f4-91fa037bb717/Paper/p3699.

[6] WHO | Antiretroviral therapy (ART) coverage among all age groups. (2018). WHO. https://www.who.int/gho/hiv/epidemic_response/ART_text/en/.

[7] Prevention, C. for D. C. and. (2015). HIV/AIDS. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids.

[8] Bernell, S., & Howard, S. W. (2016). Use Your Words Carefully: What Is a Chronic Disease? Frontiers in Public Health, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00159.

[9] Choi, B. C. K., Morrison, H., Wong, T., Wu, J., & Yan, Y. P. (2007). Bringing chronic disease epidemiology and infectious disease epidemiology back together. In Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (Vol. 61, Issue 9, p. 832). BMJ Publishing Group. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2006.057752.

[10] Unwin, N., Jordan, J. A. E., Bonita, R., Ackland, M., Choi, B. C. K., & Puska, P. (2004). Rethinking the terms non-communicable disease and chronic disease [1] (multiple letters). In Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (Vol. 58, Issue 9, p. 801). BMJ Publishing Group. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2003.015040.

[11] Swendeman, D., Ingram, B. L., & Rotheram-Borus, M. J. (2009). Common elements in self-management of HIV and other chronic illnesses: An integrative framework. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 21(10), 1321–1334. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120902803158.

[12] What is Self-Care? - ISF. (n.d.). Retrieved May 22, 2020, from https://isfglobal.org/what-is-self-care/.

[13] Riegel, B., Moser, D. K., Buck, H. G., VaughanDickson, V., B.Dunbar, S., Lee, C. S., Lennie, T. A., Lindenfeld, J. A., Mitchell, J. E., Treat-Jacobson, D. J., & Webber, D. E. (2017). Self-care for the prevention and management of cardiovascular disease and stroke: A scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart association. Journal of the American Heart Association, 6(9). https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.006997.

[14] Narasimhan, M. (n.d.). WHO Consolidated Guideline on Self-care Interventions for Health Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights.

[15] Narasimhan, M., Allotey, P., & Hardon, A. (2019). Self-care interventions to advance health and wellbeing: A conceptual framework to inform normative guidance. BMJ (Online), 365. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l688.

[16] Remme, M., Narasimhan, M., Wilson, D., Ali, M., Vijayasingham, L., Ghani, F., & Allotey, P. (2019). Self-care interventions for sexual and reproductive health and rights: Costs, benefits, and financing. BMJ (Online), 365. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1228.

[17] SELF-CARE INTERVENTIONS FOR HEALTH: SEXUAL & REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH AND RIGHTS Communications Toolkit. (2014). https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/hand.

[18] Yamane, T. (1967). 2nd Edition.

[19] Fang-Yu Chou, R. N., & Holzemer, W. L. (2004). Linking HIV/AIDS clients’ self-care with outcomes. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 15(4), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1055329003255592.

[20] Chou, F. Y., Holzemer, W. L., Portillo, C. J., & Slaughter, R. (2004). Self-care strategies and sources of information for HIV/AIDS symptom management. Nursing Research, 53(5), 332–339. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200409000-00008.

[21] Nokes, K. M., & Nwakeze, P. C. (2005). Assessing self-management information needs of persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 19(9), 607–613. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2005.19.607.

[22] Chou, F. Y. (2004). Testing a Predictive Model of the Use of HIV/AIDS Symptom Self-Care Strategies. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 18(2), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1089/108729104322802533.

[23] Okoronkwo, I. (2015). Assessing Self Care Practices of People Living with AIDS attending antiretroviral clinic Kafanchan, Kaduna State, Nigeria. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research, 06(12). https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6113.1000528.

[24] Determining Sample Size Degree of Variability. (n.d.).Onyango, A. C., Walingo, M. K., Mbagaya, G., & Kakai, R. (2012). Assessing nutrient intake and nutrient status of HIV seropositive patients attending clinic at Chulaimbo sub-district Hospital, Kenya. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/306530.

Viewed PDF 861 27 -

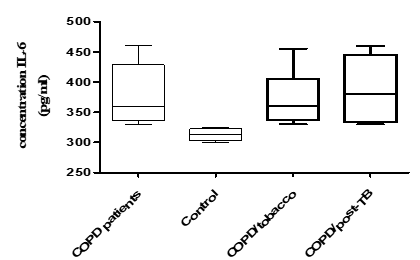

Role of Helper, Cytotoxic T-cells and Interleukin-6 amongst Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients Post Exposure to Tobacco or Tuberculosis in Yaoundé CameroonAuthor: Yayah Emerencia NgahDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art004

Role of Helper, Cytotoxic T-cells and Interleukin-6 amongst Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients Post Exposure to Tobacco or Tuberculosis in Yaoundé CameroonAuthor: Yayah Emerencia NgahDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art004Role of Helper, Cytotoxic T-cells and Interleukin-6 amongst Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients Post Exposure to Tobacco or Tuberculosis in Yaoundé Cameroon

Abstract:

The pro-inflammatory cytokine Interleukin-6 (IL-6) –and T- T-cells play a major role in the pathogenesis and prognosis of many respiratory tract infections. Our study aimed to evaluate the role of T-Lymphocyte and IL-6 in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) patients post-exposure to Tobacco or Tuberculosis. A cross-sectional prospective study was carried out from February 2021 to July 2022. Participants were enrolled at the Yaoundé Jamot Hospital. The intervention group comprised patients with post-TB/AFO (Tuberculosis/Airflow obstruction) and those with COPD related to tobacco, healthy subjects served as control. Spirometry results were obtained from the medical records. T-lymphocyte and IL-6 concentrations were measured by flow cytometry and ELISA (Enzyme-linked immunosorbent Assay) respectively. 150 participants were enrolled, 90 COPD patients and 60 healthy people. The COPD patients consisted of 50 with a history of smoking (COPD/tobacco) and 40 with a history of tuberculosis (post-TB/AFO). The level of IL-6 and CD4 cells (cluster differentiation) was higher in COPD patients compared to the control group (p-value 0.0001 and 0.0006 respectively). CD8 counts were higher in COPD/tobacco than in post-TB/AFO (p = 0.0043). IL-6 and CD4 were not statistically different between COPD/tobacco and post-TB/AFO. There was an inverse and non-significant correlation between IL-6 and CD8; and a non-significant positive correlation between IL-6 and CD4 with r = -0335, p = 0.087; R = 0.355; P = 0.069 respectively. IL-6 and CD8 T cells are involved in the pathogenesis of both COPD related to tobacco and post-TB airflow obstruction, with higher counts of blood CD8 cells in COPD/tobacco.

Keywords: COPD, Inflammation, IL-6, T-lymphocyte, Tobacco, Tuberculosis.Role of Helper, Cytotoxic T-cells and Interleukin-6 amongst Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients Post Exposure to Tobacco or Tuberculosis in Yaoundé Cameroon

References:

[1] Daniel Lange, Casey E Ciavaglia, J Alberto Neder, Katherine A., Webb, and Denis E O’Donnell. Lung hyperinflation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: mechanisms, clinical implications, and treatment. 10.1586/17476348.2014.949676 2014 Informa UK Ltd ISSN 1747-6348.

[2] GOLD: Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2019. http://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads Accessed 10 April 2020.

[3] Roche N., Huchon G. Epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Rev Prat., 2004, 54, 1408-1413.

[4] Pefura-Yone EW, Kengne AP, Tagne-Kamdem PE, Afane-Ze E. Clinical significance of low forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of vital capacity following treated pulmonary tuberculosis: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2014; 4: e005361.

[5] Dina S., Shyamala G., Adam T.C., Meldrum C.A., Raja M., Adam M. G., Jeffrey L. C., Fernando J. M., Hershenson M.B., Umadevi S. Increased Cytokine Response of Rhinovirus-infected Airway Epithelial Cells in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med Vol 182. pp 332–340, 2010 DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200911-1673OC on April 15, 2010.

[6] Buist S. MD: Global Burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence and future trends. the lancet 2007, 370:765-773.

[7] Gadgil A., Duncan S.R. Role of T-lymphocytes and pro-inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. International Journal of COPD 2008:3(4) 531–541.

[8] Guiedem Elise, Mondinde Ikomey George, Nkenfou Céline, Pefura‑Yone Eric Walter, Mesembe Martha, Chegou Njweipi Novel, Graeme Brendon Jacobs, Okomo Assoumou Marie Claire. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes in patients with anterior tuberculosis compared to tobacco-related COPD. BMC Res Notes. 2018 ; 11 :192.

[9] Grubek-Jaworska H., Paplinska M., Hermanowiecz-Salamon J., Bialek-Gosk K., Dabrowska M., Grabczak E. IL-6 and IL-13 in induced sputum, of COPD and Asthma patients: correlation with respiratory tests. Respiration, 2012, 84(2), 7-101.

[10] Celli B., Locantore N., Yates J., Tal-Singer R., Miller B., Bakke P. Inflammatory biomarkers improve clinical prediction of mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. Am J respir crit care Med., 185, 72-106572.

[11] Suleyman S.H., Hakan G., Levent C.M., Aysun B.K., Ismail T. Association between cytokines in induced sputum and severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 0954-6111. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.08.022.

[12] Hurst J.R., Perera W.R., Wilkinson T.M., Donaldson G.C., Wedzicha J.A. Systemic and upper and lower airway inflammation at exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173: 71-78

[13] Mallia P, Message SD, Contoli M, et al. Lymphocyte subsets in experimental rhinovirus infection in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2014 ;108(1)78-85. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2013.09.010.

[14] Gadgil A., Zhu X., Sciurba F., Ducan S. altered T-cell phenotypes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006; 3:487–8.

[15] Mikhak Z, Farsidjani A, Luster AD. Endotoxin augmented antigen induced Th1 cell trafficking amplifies airway neutrophilic inflammation. J Immunol. 2009; 182(12): 7946-7956. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.0803522.

[16] Mustimbo E.P, Higgs BW, Brohawn P, Brohawn, Pilataxi F., Xiang G., Kuziora M., Bowler R.P., White W.I. CD4+ T-cell profiles and peripheral blood ex-vivo responses to T-cell directed stimulation delineate COPD phenotypes. J COPD F. 2(4): 268-280. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2.4.2015.0131.

[17] Roberts MEP, Higgs BW, Brohawn P, et al. CD4+ T-cell profiles and peripheral blood ex-vivo responses to T-cell directed stimulation delineate COPD phenotypes. J COPD F. 2(4): 268-280.

[18] Dienz O., Eaton S., Bond J., Neveu W., Moquin D., Noubade R. The induction of antibody production by IL-6 is indirectly mediated by IL-12 produced by CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med., 2009, 206, 69-78.

[19] Dina S., Shyamala G., Adam T.C., Meldrum C.A., Raja M., Adam M. G., Jeffrey L. C., Fernando J. M., Hershenson M.B., Umadevi S. Increased

Cytokine Response of Rhinovirus-infected Airway Epithelial Cells in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med Vol 182. pp 332–340, 2010 DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200911-1673OC.[20] Aubier M., Marthan R., Berger P., Chambellan A., Chanez P., Aguilaniu B. BPCO et Inflammation : mise au point par un groupe d’experts. Les mécanismes de l’inflammation et du remodelage. 0761-8425/S. doi : 10.1016/j.rmr.2010.10.004.

[21] Perez T., Mal H., Aguilaniu B., Brillet P.Y., Chaouat A., Louis R., Muir, J.-F. et al. BPCO et inflammation : mise au point d’un groupe d’experts. Les phénotypes en lien avec l’inflammation. 2010, 10.1016/j.rmr.

Viewed PDF 841 48 -

Properties of Natural Materials as Alternative to Nylon Bristles – An Exploratory Study for Reduction of Polymer UsageAuthor: Murukesan SDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art005

Properties of Natural Materials as Alternative to Nylon Bristles – An Exploratory Study for Reduction of Polymer UsageAuthor: Murukesan SDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art005Properties of Natural Materials as Alternative to Nylon Bristles – An Exploratory Study for Reduction of Polymer Usage

Abstract:

Background: Nylon bristles are the most commonly used type of bristle in toothbrushes, but they have both advantages and disadvantages. Nylon bristles can be too hard or abrasive for some people's teeth and gums. Nylon is not biodegradable and can harbor bacteria if not cleaned properly. Aims: In order to explore the possibility of using natural fibers this study was conducted. Materials and Methods: Twigs of neem, banyan, babool and miswak were purchased as fresh twigs, wiped clean, hammered on a hard wood base to obtain fibers of desired lengths. Physical appearance, Bend Recovery, Folding Endurance and Antibacterial adhesion against B. Subtilis were evaluated. All experiments were performed as triplicate and mean and standard deviation were reported. Results: Digital microscopy showed well defined fibers of fairly constant diameter, apparent from the superimposed scale. Results of bend recovery analysis showed that miswak fibers were flexible and recovery was good. Folding Endurance test showed miswak and banyan were having great folding endurance. Bacterial adhesion with B. Subtilis was heavy in all fibres. The antibacterial activity of four extracts showed that all groups had identifiable antimicrobial activity at 2000 µg concentrations. Conclusion: From results of the study, it can be inferred that miswak is the most suitable material to be used for fabricating bristles in its native form.

Keywords: Babool, Banyan, Bristles, Natural Fibres; Neem Miswak.Properties of Natural Materials as Alternative to Nylon Bristles – An Exploratory Study for Reduction of Polymer Usage

References:

[1] ADA.org. (2012, November 12). Toothbrushes – American Dental Association. https://www.ada.org/en/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/oral-health-topics/toothbrushes.

[2] Plastic toothbrush – Design life. (2023, June 15). http://www.designlife-cycle.com/plastic-toothbrush#:~:text=The%20materials%20that%20are%20used,the%20main%20material%20of%20bristles.

[3] Phillips, R. W., & Swartz, M. L., 1953, Effects of diameter of nylon bristles on enamel surface. Journal of the American Dental Association, 47(1), 20–26.

[4] Rajeswaran, S. A., & Sankari Malaiappan, D. J. AS SG.,2021, A Comparative Study on the efficacy of plaque removal of three natural toothbrushes-an in-vitro study. NVEO-natural volatiles and essential oils Journal, 6054–6069.

[5] Offsets, C. Calculator CF. Biodegradable bamboo toothbrush: Greenwashing or eco-friendly?

[6] Assari, A. S., Mohammed Mahrous, M., Ahmad, Y. A., Alotaibi, F., Alshammari, M., AlTurki, F., & AlShammari, T., 2022, Efficacy of different sterilization techniques for toothbrush decontamination: An ex vivo study. Cureus, 14(1), e21117.

[7] E. I. du Pont de Nemours, 1979, Stiffness: Folding endurance test. Bend recovery of TYNEX® and HEROX® nylon filaments, technical data Bulletin No. 5. Plastics Department.

[8] Nair, A. B., Kumria, R., Harsha, S., Attimarad, M., Al-Dhubiab, B. E., & Alhaider, I. A., 2013, In vitro techniques to evaluate buccal films. Journal of Controlled Release, 166(1), 10–21.

[9] Khan, G., Yadav, S. K., Patel, R. R., Nath, G., Bansal, M., & Mishra, B., 2016, Development and evaluation of biodegradable chitosan films of metronidazole and levofloxacin for the management of periodontitis. AAPS PharmSciTech, 17(6), 1312–1325.

[10] Carranza, F. A., 2003, Clinical periodontology (9th ed). Saunders.

[11] Wilkins, E. M., McCullough, P. A., 1999, Clinical practice of the dental hygienist (3rd ed). Lea & Febiger.

[12] Bass, C. C. (1948). The optimum characteristics of toothbrushes for personal oral hygiene. Dental Items of Interest, 70(7), 697–718.

[13] Hine, M. (1956). The toothbrush. International Dental Journal. Google Scholar, 6, 15–25.

[14] Kumar, S., Kumari, M., Acharya, S., & Prasad, R., 2014, Comparison of surface abrasion produced on the enamel surface by a standard dentifrice using three different toothbrush bristle designs: A profilometric in vitro study. Journal of Conservative Dentistry, 17(4), 369–373.

[15] Nur Diyana, A. F., Khalina, A., Sapuan, M. S., Lee, C. H., Aisyah, H. A., Nurazzi, M. N., & Ayu, R. S., 2022, Physical, mechanical, and thermal properties and characterization of natural fiber composites reinforced poly (lactic acid): Miswak (Salvadora persica L.) fibers. International Journal of Polymer Science, 2022, 1–20.

[16] Thandavamoorthy, R., & Palanivel, A., 2020, Testing and evaluation of tensile and impact strength of neem/banyan fiber-reinforced hybrid composite. Journal of Testing and Evaluation, 48(1), 647–655.

[17] Mrudhula, R., Dinesh Sankar Reddy, P., & Veeresh Kumar, G. B., 2023, Preparation of cellulose nanofibers (CNFs) from Cajanus cajan (pigeon pea) and Acacia arabica (babul plant). In Recent trends in product design and intelligent manufacturing systems (pp. 429–438). Springer Nature Singapore.

[18] Al-Bayati, F. A., & Sulaiman, K. D., 2008, In vitro antimicrobial activity of Salvadora persica L. extracts against some isolated oral pathogens in Iraq. Turkish Journal of Biology, 32, 57–62.

[19] Sofrata, A. H., Claesson, R. L., Lingström, P. K., & Gustafsson, A. K., 2008, Strong antibacterial effect of miswak against oral microorganisms associated with periodontitis and caries. Journal of Periodontology, 79(8), 1474–1479.

[20] Almas, K., & Al-Zeid, Z., 2004, The immediate antimicrobial effect of a toothbrush and miswak on cariogenic bacteria: a clinical study. The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice, 5(1), 105–114.

[21] Elangovan, A., Muranga, J., & Joseph, E., 2012, Comparative evaluation of the antimicrobial efficacy of four chewing sticks commonly used in South India: An in vitro study. Indian Journal of Dental Research, 23(6), 840.

[22] Norton, M. R., & Addy, M., 1989, Chewing sticks versus toothbrushes in West Africa. A pilot study. Clinical Preventive Dentistry, 11(3), 11–13.

[23] Gazi, M., Saini, T., Ashri, N., & Lambourne, A., 1990, Meswak chewing stick versus conventional toothbrush as an oral hygiene aid. Clinical Preventive Dentistry, 12(4), 19–23.

[24] Al-Otaibi, M., Al-Harthy, M., Söder, B., Gustafsson, A., & Angmar-Månsson, B., 2003, Comparative effect of chewing sticks and tooth brushing on plaque removal and gingival health. Oral Health and Preventive Dentistry, 1(4), 301–307.

Viewed PDF 1052 49 -

Analysis of Quality and Quantity of Complementary Feeding and Nutrition among Children of 6 to 36 Months in Maiduguri Metropolitan Council, Borno State, NigeriaAuthor: Nyeapa YakubuDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art006

Analysis of Quality and Quantity of Complementary Feeding and Nutrition among Children of 6 to 36 Months in Maiduguri Metropolitan Council, Borno State, NigeriaAuthor: Nyeapa YakubuDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art006Analysis of Quality and Quantity of Complementary Feeding and Nutrition among Children of 6 to 36 Months in Maiduguri Metropolitan Council, Borno State, Nigeria

Abstract:

This paper provides a cross sectional analysis of the quality and quantity of complimentary feeding and nutrition among children of 6-36 months in Maiduguri Metropolitan Council. The role of health workers and parents in contextualities in driving, constraining or otherwise influencing complimentary feeding practices is explored through a review of the essential literature. Though this literature is found to have considerably expanded the scope of understanding around health and nutrition, research in the area is found to be lacking in methodological coherence and theoretical substance. Future efforts are needed to systematically bring together the array of insights, methodological approaches, and recommendations in this literature, as well as better bound, differentiate and systemize health and nutrition research in the area going forward. Two initial objectives are advanced through this paper in relation to this dual research imperative. They employed the survey research method. It revealed that knowledge of complementary feeding amongst women in emergencies are poor and government need to scale up support through local enlightenment programs that will boost good health and nutritional practices.

Keywords: Complementary Feeding, Nutrition, Quality of complimentary feeding, Maiduguri Metropolitan Council, Nigeria.Analysis of Quality and Quantity of Complementary Feeding and Nutrition among Children of 6 to 36 Months in Maiduguri Metropolitan Council, Borno State, Nigeria

References:

[1] Black RE, Victoria CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, De Onis M, Ezzati M, Grantham S, Katz J, Martorell R and Uauy R; .2013. Maternal and Child Nutrition and Underweight in Low-Income Countries.

[2] Global Nutrition Report 2008. Shining a light to spur action on nutrition. Retrieved from https://globalnutritionreport.org/reports/global-nutrition-report-2018/.

[3] Saha KK, Persson L, Rasmussen KM, Arifeen SE, Frongillo EA, et al. 2008. Appropriate infant feeding practices result in better growth of infants and young children in rural Bangladesh. Am J ClinNutr. 2008; 87: 1852-1859. Ref.: https://goo.gl/BhETH9.

[4] Pelto G.H., 2000. Improving Complementary Feeding Practices Responsive Parenting as a Primary Component Of Intervention To Prevent Malnutrition In Infancy and Early Childhood. Pediatrics. 2000; 106: 1300-1301. Ref.: https://goo.gl/rH6JHw.

[5] Müller O, Krawinkel M., 2005. Malnutrition and health in developing countries. CMAJ. 2005 173: 279-86. Ref.: https://goo.gl/SrR5Eb.

[6] Chesire EJ, Orago AS, Oteba LP, Echoka E, 2008. Determinants of under nutrition among school age children in a Nairobi peri-urban slum. East Afr Med J. 2008;85(10):471–9.

[7] UNICEF, WHO, World Bank Group. Levels and trends in child malnutrition. New York. The World Bank Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates; 2015.

[8] Munthali T, Jacobs C, Sitali L, Dambe R, Michelo C (2015). Mortality and morbidity patterns in under-five children with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in Zambia: a five-year retrospective review of hospital-based records (2009-2013). Arch Public Health. 2015;73(1):146. doi:10.1186/s13690-015-0072-1.

[9] NDHS: 2013; National Population Commission (NPC) (Nigeria) and ICF International. (2014). Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF International. Retrieved from https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr293/fr293.pdf.

[10] NDHS: 2018: National Population Commission (NPC) (Nigeria) and ICF (2019). Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018. Abuja, Nigeria and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF. Retrieved from https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr359/fr359.pdf.

[11] Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2016 – 2017.

[12] Aggarwal A., Verman, S., Faridi, M & Dayachand 92008). Complementary feeding – reasons for inappropriateness in timing, quantity, and consistency. Indian Journal of Pediatrics 75 (1): 49 – 53.

[13] World Health Organisation, Children: reducing mortality. Fact sheet. [Accessed November 30, 2016] http://www.who.int.mediacentre/factshetts/fs178/en/.

[14] World Health Organization Infant and young child feeding. 2016. [Accessed March 31st, 2016] http://who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs342/en/.

[15] WHO (2013). Essential Nutrition Actions: Mainstreaming Nutrition through the Life-Course. World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/84409/9789241505550_eng.pdf?sequence=1.

[16] WHO 2003. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/global_strategy/en/.

[17] Zere, E., and Mcintyre D. 2003. Inequities in under-five child malnutrition South Africa. International Journal for Equity in Health, 2(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-2-7.

[18] World Health Organization: Standards for Maternal and Neonatal Care 2006.

[19] Victora CG, de Onis M, Hallal PC, Blossner M and Shrimpton R. 2010. Worldwide timing of growth faltering: revisiting implications for interventions. Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):473-480.

[20] Moore AC, Akhter S, Aboud FE. 2006. Responsive complementary feeding in rural Bangladesh. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(8):1917-1930.

[21] Ivankova, N.V., Cresswell, J. W. & Stick, S. L 2006. Using Mixed Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice. Sage Publications, 18(3) 3 - 11. Doi:10.1177/1525822X05282260.

Viewed PDF 6480 60 -

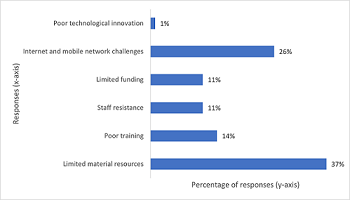

Telehealth Utilisation in HIV Care Services in Harare, Zimbabwe: Awareness and Acceptability among Healthcare WorkersAuthor: Stanford ChigaroDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art007

Telehealth Utilisation in HIV Care Services in Harare, Zimbabwe: Awareness and Acceptability among Healthcare WorkersAuthor: Stanford ChigaroDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art007Telehealth Utilisation in HIV Care Services in Harare, Zimbabwe: Awareness and Acceptability among Healthcare Workers

Abstract:

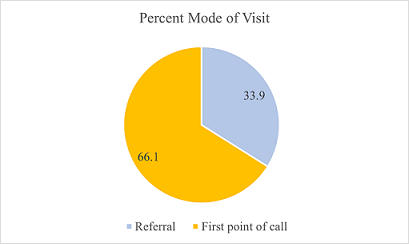

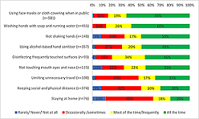

Access to healthcare in developing countries is generally poor due to limited health facilities and shortage of healthcare workers. Recent developments in technology and telehealth promise to address challenges of access to health facilities through remote service provision. However, the level of awareness and acceptability of telehealth in HIV care among healthcare workers in Zimbabwe is not well known. The main objective of this study is to assess the level of awareness and acceptability of telehealth among healthcare workers involved in HIV care in Harare, Zimbabwe. A cross-sectional survey was employed to conveniently sample and interview 395 healthcare workers from 15 public healthcare facilities and 34 private healthcare facilities in Harare. A pretested questionnaire was employed to collect data. Logistic regression analysis was carried out to establish possible association of the independent variable and dependent variables (awareness and acceptance). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 28.0.1.1. Of the 395 healthcare workers interviewed, 87% were aware of telehealth, while 85% found it acceptable. Logistic regression analysis identified educational level, and type of profession to be significantly (p < 0.05) associated with telehealth awareness. There was an association between telehealth acceptance and level of education (p < 0.05). Lack of resources was a major barrier to telehealth utilisation. The findings of this study reveal high awareness and acceptability of telehealth in HIV care among healthcare workers in Harare. The findings provide optimism for telehealth uptake and the promotion of telehealth as an important intervention in HIV care.

Keywords: Acceptability, Awareness, HIV care, Telehealth.Telehealth Utilisation in HIV Care Services in Harare, Zimbabwe: Awareness and Acceptability among Healthcare Workers

References:

[1] World Health Organization. (n.d.). Social determinants of health. Retrieved 3 August 2022, from https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1.

[2] Loewenson, R., & Masotya, M. (2018). Equity Watch: Assessing progress towards equity in health in Zimbabwe, 2018 Training and Research Support Centre, Regional Network for Equity in Health in East and Southern Africa (EQUINET). https://www.tarsc.org/publications/documents/Zim%20equitywatch%2009.pdf.

[3] Mangundu, M., Roets, L., & Van Rensberg, E. J. (2020). Accessibility of healthcare in rural Zimbabwe: The perspective of nurses and healthcare users. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v12i1.2245.

[4] Tessema, Z. T., Worku, M. G., Tesema, G. A., Alamneh, T. S., Teshale, A. B., Yeshaw, Y., Alem, A. Z., Ayalew, H. G., & Liyew, A. M. (2022). Determinants of accessing healthcare in Sub-Saharan Africa: A mixed-effect analysis of recent Demographic and Health Surveys from 36 countries. BMJ Open, 12(1), e054397. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054397.

[5] Oleribe, O. E., Momoh, J., Uzochukwu, B. S., Mbofana, F., Adebiyi, A., Barbera, T., Williams, R., & Taylor Robinson, S. D. (2019). Identifying Key Challenges Facing Healthcare Systems In Africa And Potential Solutions. International Journal of General Medicine, Volume 12, 395–403. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S223882.

[6] Druetz, T. (2018). Integrated primary health care in low- and middle-income countries: A double challenge. BMC Medical Ethics, 19(S1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-018-0288-z.

[7] Tafuma, T. A., Mahachi, N., Dziwa, C., Moga, T., Baloyi, P., Muyambo, G., Muchedzi, A., Chimbidzikai, T., Ncube, G., Murungu, J., Nyagura, T., & Lew, K. (2018). Barriers to HIV service utilisation by people living with HIV in two provinces of Zimbabwe: Results from 2016 baseline assessment. Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine, 19(1), 721. https://doi.org/10.4102/hivmed.v19i1.721.

[8] Keesara, S., Jonas, A., & Schulman, K. (2020). Covid-19 and Health Care’s Digital Revolution. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(23), e82. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2005835.

[9] Health Resources and Services Administration. (2020). Glossary. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/glossary#t.

[10] Lurie, N., & Carr, B. G. (2018). The Role of Telehealth in the Medical Response to Disasters. JAMA Internal Medicine, 178(6), 745. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1314.

[11] Miyawaki, A., Tabuchi, T., Ong, M. K., & Tsugawa, Y. (2021). Age and Social Disparities in the Use of Telemedicine During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Japan: Cross-sectional Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(7), e27982. https://doi.org/10.2196/27982.

[12] Williams, C., & Shang, D. (2023). Telehealth Usage Among Low-Income Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Retrospective Observational Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, e43604. https://doi.org/10.2196/43604.

[13] Fouad, A. A., Osman, M. A., Abdelmonaem, Y. M. M., & Karim, N. A. H. A. (2023). Awareness, knowledge, attitude, and skills of telemedicine among mental healthcare providers. Middle East Current Psychiatry, 30(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-022-00272-3.

[14] Ammenwerth, E. (2019). Technology Acceptance Models in Health Informatics: TAM and UTAUT. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 263, 64–71. https://doi.org/10.3233/SHTI190111.

[15] Venkatesh, Morris, Davis, & Davis. (2003). User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540.

[16] López-Cabarcos, M. Á., Piñeiro-Chousa, J., & Quiñoá-Piñeiro, L. (2021). An approach to a country’s innovation considering cultural, economic, and social conditions. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 34(1), 2747–2766. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2020.1838314.

[17] Chitungo, I., Mhango, M., Mbunge, E., Dzobo, M., Musuka, G., & Dzinamarira, T. (2021). Utility of telemedicine in sub‐Saharan Africa during the COVID ‐19 pandemic. A rapid review. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(5), 843–853. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.297.

[18] Furusa, S. S., & Coleman, A. (2018). Factors influencing e-health implementation by medical doctors in public hospitals in Zimbabwe. SA Journal of Information Management, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.4102/sajim.v20i1.928.

[19] International Center for AIDS Care and Treatment Program (2020). Zimbabwe population-based HIV impact assessment. https://phia.icap.columbia.edu/zimbabwe2020-final-report/

[20] Banya, N. (2018). Zimbabwe’s health delivery system. ZimFact. https://zimfact.org/factsheet-zimbabwes-health-delivery-system/.

[21] Raosoft. (2004). Sample Size Calculator. http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html.

[22] Mugarisi, V. (2022). Zimbabwe conducts health labour market analysis. World Health Organization. https://www.afro.who.int/countries/zimbabwe/news/zimbabwe-conducts-health-labour-market-analysis.

[23] Gurupur, V. P., & Wan, T. T. H. (2017). Challenges in implementing mHealth interventions: A technical perspective. MHealth, 3, 32–32. https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth.2017.07.05.

[24] Ministry of Child and Child Care. (n.d.). National Health Strategy 2020-2025 on the cards. Retrieved 3 September 2023, from http://www.mohcc.gov.zw/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=343:national-health-strategy-2020-2025-on-the-.

[25] Naqvi, S. Z., Ahmad, S., Rocha, I. C., Ramos, K. G., Javed, H., Yasin, F., Khan, H. D., Farid, S., Mohsin, A., & Idrees, A. (2022). Healthcare Workers’ Knowledge and Attitude Toward Telemedicine During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Global Survey. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.30079.

[26] Elhadi, M., Elhadi, A., Bouhuwaish, A., Bin Alshiteewi, F., Elmabrouk, A., Alsuyihili, A., Alhashimi, A., Khel, S., Elgherwi, A., Alsoufi, A., Albakoush, A., & Abdulmalik, A. (2021). Telemedicine Awareness, Knowledge, Attitude, and Skills of Health Care Workers in a Low-Resource Country During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-sectional Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(2), e20812. https://doi.org/10.2196/20812.

[27] Ayatollahi, H., Sarabi, F. Z. P., & Langarizadeh, M. (2015). Clinicians’ Knowledge and Perception of Telemedicine Technology. Perspectives in Health Information Management, 12(Fall), 1c.

[28] Renu, N. (2021). Technological advancement in the era of COVID-19. SAGE Open Medicine, 9, 205031212110009. https://doi.org/10.1177/20503121211000912.

[29] Mahtta, D., Daher, M., Lee, M. T., Sayani, S., Shishehbor, M., & Virani, S. S. (2021). Promise and Perils of Telehealth in the Current Era. Current Cardiology Reports, 23(9), 115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-021-01544-w.

[30] Yaghobian, S., Ohannessian, R., Iampetro, T., Riom, I., Salles, N., De Bustos, E. M., Moulin, T., & Mathieu-Fritz, A. (2022). Knowledge, attitudes and practices of telemedicine education and training of French medical students and residents. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 28(4), 248–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X20926829.

[31] Ncube, B., Mars, M., & Scott, R. E. (2023). Perceptions and attitudes of patients and healthcare workers towards the use of telemedicine in Botswana: An exploratory study. PLOS ONE, 18(2), e0281754. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281754.

Viewed PDF 1016 47 -

Assessing the Availability and Utilisation of Adolescent Reproductive Health Services in Northern Region of GhanaAuthor: Abdul-Malik AbdulaiDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art008

Assessing the Availability and Utilisation of Adolescent Reproductive Health Services in Northern Region of GhanaAuthor: Abdul-Malik AbdulaiDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art008Assessing the Availability and Utilisation of Adolescent Reproductive Health Services in Northern Region of Ghana

Abstract:

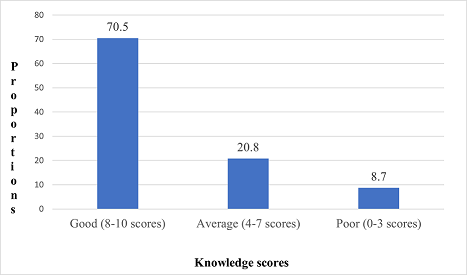

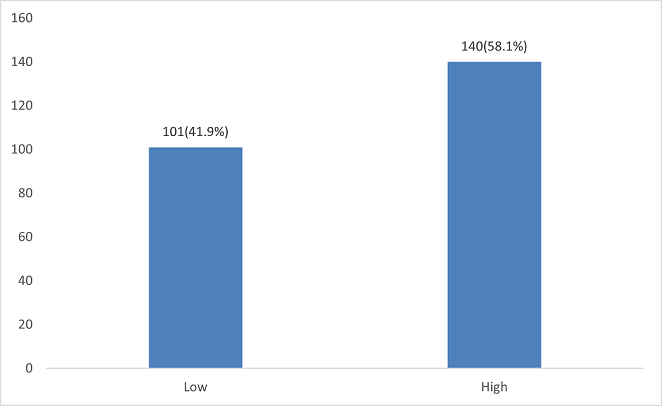

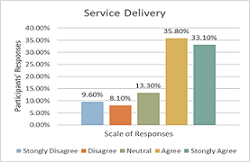

Youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services involved range of Sexual and Reproductive Health services that are delivered to the specific needs, vulnerabilities, and desires of young people. This study aims to determine the availability and utilization of adolescent sexual and reproductive health services among youths in selected districts and municipalities in the Northern Region of Ghana. A descriptive cross-sectional study design was conducted in four selected districts using a mixed method of quantitative and qualitative approaches to data collections. Both male and female adolescent and young person aged 10-24 years were selected by simple random sampling through balloting. Convenient sampling was used to select four health workers for interviews. Quantitative data was analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics, and qualitative analysis was done using manual thematic analysis. The qualitative data was collected using an unstructured interview guide and analysed with thematic analysis. Findings showed average age was 16.64 years, and 70.5% had good knowledge score of SRH services availability. Types of SRH services provided include counselling and education on SRH issues, STIs screening, diagnosis, and management. About 69.8% have ever visited the health facilities for SRH service, and 36.1% covered more than an hour before accessing SRH services. About 21% had access contraceptives and family planning services. Barriers to accessing SRH services were attributed to; cost of healthcare (21.9%), long queues at facilities (15.3%), and distance to healthcare facility (12.4%). Associated factors were sex (OR = 1.72; 95%CI 1.16-2.57; p = 0.007), father educational attainment (OR = 2.03; 95%CI 1.35-3.03; p = 0.0001), and district of residence (OR = 5.72; 95%CI 2.01-16.25; p = 0.0005). Most adolescents and young people from the study findings had increased knowledge score on the types and availability of SRH services in the district health facilities. But utilization of the SRH services was low because, the point of delivery of these SRH services were far, and most have to cover long distance.

Keywords: Adolescent, Availability, Utilization, Reproductive Health Service, Ghana.

Assessing the Availability and Utilisation of Adolescent Reproductive Health Services in Northern Region of Ghana

References:

[1] World Health Organization. (2018). Family Planning Evidence Brief: Reducing early and unintended pregnancies among adolescents. WHO/RHR/17.10. www.who.int.

[2] Bam, V., Bilal, S.M., Spigt, M., Dinant, G. J., & Blanco, R., (2019). Utilization of sexual and reproductive health services in Ethiopia. Does it affect sexual activity among high school students? Journal of Sexual Reproductive Health, 6(1), 14-18.

[3] Abajobir, A. A., & Seme, A. (2014). Reproductive health knowledge and services utilization among rural adolescents in east Gojjam zone, Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 1–11.

[4] Ghana Statistical Service (2014). Ghana demographic and health survey,2015. Rockville, Maryland, USA: GSS, GHS, and ICF International.

[5] Ghana Health Service (2016). Monthly family planning performance feedback (Fact sheet). Accra: GHS, MOH. April 2.

[6] Kumi-Kyereme, A., (2021). ‘Sexual and reproductive health services utilisation amongst in-school young people with disabilities in Ghana’, African Journal of Disability 10(0), a671.

[7] Maguire, M., & Delahunt, B. (2017). Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by step guide for learning and teaching scholars. Dundalk in state of technology. J of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 8(3).

[8] Awusabo-Asare, K., Yankey, B.A., Baiden, F., & Eliason, S. (2014). Determinants of unintended pregnancies in rural Ghana. BMC J of pregnancy and childbirth, 14 (2015), 1-9.

[9] Ajike, S. O., & Mbegbu, V. C. (2016). Adolescent / Youth utilization of reproductive health services : Knowledge still a barrier. The Need for Adolescents and Youths. PloS One Journal, 2(3), 17–22.

[10] Dapaah, J. M., Christopher, S., Appiah, Y., Amankwaa, A., & Ohene, L. R. (2016). Knowledge about Sexual and Reproductive Health Services and Practice of What Is Known among Ghanaian Youth , a Mixed Method Approach. January, 1–13.

[11] Bedho, C., Bankole, A., & Malarcher, S. (2014). Removing barriers to adolescents’ access to contraceptive information and services. J Studies in Fam Planning, 4(1), 117–124.

[12] Akatukwasa, C., Bajunirwe, F., Nuwamanya, S., Kansime, N., Aheebwe, E., & Tamwesigire, I. K. (2019). Integration of HIV-sexual reproductive health services for young people and the barriers at public health facilities in Mbarara Municipality , Southwestern Uganda : A qualitative assessment. BMJ Journal, 12(3).

[13] Binu, W., Marama, T., Gerbaba, M., & Sinaga, M. (2018). Sexual and reproductive health services utilization and associated factors among secondary school students in Nekemte town, Ethiopia. Bio Med Central, Reproductive Health, 15 (64), 1-10.

[14] Luvai, U.N., Kipmerewo, M., & Onyango, O.K. (2017). Utilization of youth friendly reproductive health services among the youth Bureti Sub County in Kenya (Abstract). European Journal of Pharmaceutical and Medical Research, 4(4), 203-212.

[15] Murigi, M., Butto, D., Barasa, S., Maina, E., & Munyalo, B. (2016). Over coming barriers to contraceptive uptake among adolescents: Kiambu County , Kenya. 05(3), 1–10.

[16] McIntyre, P., Glen, W., & Peattie, S. (2012). Peer influence on sexual activities among adolescents in Ghana. Population Council, 4(6),1, 1.19.

[17] Schalet, A.T., Santelli, J.S., Russell, S.T., & Halpern, C.T. (2014). Adolescence building solid foundations for long life flourishing: World Health Organization. The European Magazine for Sexual and reproductive Health, 80.

[18] Darrroch, J.E., Woog, V., Bankole, A., & Ashford, L.S. (2016). Adding it up: Costsand benefits of meeting the contraceptives needs of adolescents. New York; Guttmacher Institute.

[19] Tlaye, K. G., Belete, M. A., Demelew, T. M., & Getu, M. A. (2018). Reproductive health services utilization and its associated factors among adolescents in Debre Berhan town , Central Ethiopia : a community-based cross-sectional study. 1–11.

[20] Igras, S. M., Macieira, M., Murphy, E., & Lundgren, R. (2014). Investing in very young adolescents ‘ sexual and reproductive health. Global Public Health, 9(5), 555–569.

[21] Pinyopornpanish, K., Thanamee, S., & Angkurawaranon, C. (2017). Sexual health, risky sexual behavior and condom use among adolescents’ young adults and older adults in Chiang Mai, Thailand: Findings of a population-based survey. BMC Research Journal, 10 (1), 682.

[22] Shayan, Z. (2015). Gender Inequality in Education in Afghanistan : Access and Barriers. May, 277–284.

[23] Breaken, P., & Rondinelli, K.A. (2012). Work-family interference among Ghanaian women in higher status occupations. (Ph.DThesis), University of Nottingham, Nottingham.

[24] Asibi, A.A.& Anaba, E.A., (2019). Barriers on access to and use of adolescent health services in Ghana. Journal of Health Research, 33(3), 197-207.

[25] Kuhn, I. (2019). Advancing the sexual and reproductive health rights of adolescent girls and young woman: A focus on safe abortion in 2030, Agenda for sustainable development. Chapel Hill, USA. Advocates for Youth. www.advocatesforyouth.org

[26] Abrafi, B., Weller, W. E., Minkovitz, C. S., & Anderson, G. F. (2018). Utilization of medical and health-related services among school-age children and adolescents with special health care needs (1994 national health interview survey on disability [NHIS-D] baseline data). Pediatrics,11(2), 593–603.

[27] Geremew, G., Tlaye, K., Belete, M. A., Demelew, T. M., & Getu, M. A. (2018). Reproductive health services utilization and its associated factors among adolescents in Debre Berhan town, Central Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study, 1–1.

[28] Ivanova, O., Rai, M., & Kemigisha, E. (2018). A systematic review of sexual and reproductive health knowledge, experiences, and access to services among refugee, migrant and displaced girls and young women in Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(8), 1583.

[29] Morris, J. L., & Rushwan, H. (2015). International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics Adolescent sexual and reproductive health : The global challenges. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 131, S40–S42.

[30] Ganchimeg, T., Ota, E., Morisaki, N., Laopaiboon, M., Lumbiganon, P., & Zhang, J. (2014). Pregnancy and childbirth outcomes among adolescent mothers: a World Health Organization multicountry study. BJOG : An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 121 Suppl(June 2018), 40–48.

Viewed PDF 871 33 -

An Investigation into NAFDAC Intervention on the Incidence of Fake and Counterfeit Drugs in NigeriaAuthor: Olakunle Daniel OlaniranDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art009

An Investigation into NAFDAC Intervention on the Incidence of Fake and Counterfeit Drugs in NigeriaAuthor: Olakunle Daniel OlaniranDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art009An Investigation into NAFDAC Intervention on the Incidence of Fake and Counterfeit Drugs in Nigeria

Abstract:

Various interventions, including innovative technologies, have been used to solve problems. Over the years, the Nigerian government has introduced a good healthcare delivery system, including providing quality, efficacious and affordable drugs. The study used a qualitative design method adopting a focus group discussion approach. The selected states for the study are Lagos, Kano, Anambra and FCT Abuja. The study population comprised NAFDAC stakeholders who are dealers in pharmaceutical products or Marketing Authorization Holders (MAHs) of medicines, Consumers and Policymakers. The focus group participants were selected based on convenience sampling. The interventions highlighted were Mobile Authentication Services (MAS), on-the-spot checks on drugs through a TruScan, Black-Eye and Radio Frequency Identification Devices (RFID). The respondents also highlighted using NAFDAC registration numbers and holograms as important ways of checking the features of medicine before using it. The participants also highlighted the lack of public awareness about these interventions and the need for proper regulation and enforcement of laws against the sale and distribution of fake drugs as challenges that hinder the successful development and implementation of interventions against fake and counterfeit drugs. The participants suggested KYC measures to address issues within the supply chain to evaluate the effectiveness of their current strategies. Regular meetings, advocacy efforts, and educational workshops are recommended to raise awareness and educate stakeholders about their roles and responsibilities in pursuit of addressing the challenges related to counterfeit drug interventions.

Keywords: Focus group discussion (FGD), Investigation, Intervention, Counterfeit, Technology.An Investigation into NAFDAC Intervention on the Incidence of Fake and Counterfeit Drugs in Nigeria

References:

[1] Buowari, O. V. (2012). Fake and Counterfeit Drug: A review. AFRIMEDIC Journal, 3(2), 1–4. http://www.ajol.info/index.php/afrij/article/view/86573.

[2] Akunyili D., (2007). Counterfeit medicines: A serious crime against humanity. Proceedings of the Director General of the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC), Nigeria, to the European Parliament in Brussels. 1–7.

[3] Amadi, L., & Amadi2, M. (2014a). Sustainable Drug Consumption, Regulatory Dynamics and Fake Drug Repositioning in Nigeria: A Case of NAFDAC. Journal of Scientific Issues, 2(9), 412–419. http://www.sci-afric.org.

[4] Adelusi A J (2000) Drug Distribution: Challenges and Effects on The Nigerian Society. Keynote address at the &3rd Annual National Conference of the Pharmaceutical Society of Nigeria held at Nicon Hilton Hotel, Abuja ,6th -10th, November 2000.

[5] Akinyandenu O (2013) Counterfeit drugs in Nigeria: A threat to public health. African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. Vol. 7(36), pp. 2571-2576.

[6] Reggi, V. (2007). Counterfeit medicines: An intent to deceive. International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine, 19(1/2), 105–108. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=25215283&site=ehost-live.

[7] Ubajaka, C. F., Obi-okaro, A. C., Emelumadu, O. F., Azumarah, M. N., Ukegbu, A. U., & Ilikannu, S. O. (2016). Factors Associated with Drug Counterfeit in Nigeria : A Twelve Year Review. 12(4), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.9734/BJMMR/2016/21342.

[8] Akunyili, D. (2010). The challenges faced by NAFDAC in the National regulatory process relate to essential drugs for preventing maternal and newborn deaths in Nigeria. Tropical Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 27(April 2010).

[9] NAFDAC. (2017). NAFDAC Anti-counterfeiting Strategies. https://www.nafdac.gov.ng/about-nafdac/nafdac-anti-counterfeiting-strategies/.

[10] Horalek, J. & Sobeslav, V (2017). Track & Trace System with Serialization Prototyping Methodology for Pharmaceutical Industry in EU. 14th International Conference, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-65515-4_15.

[11] Egwu, P. E. (2018). Audience exposure and attitude towards NAFDAC’S ‘Mobile Authentication Service’ (MAS) campaigns in three selected southeast states. In Energies (Vol. 6, Issue 1). https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjFkJvyhujAhWTM8AKHc7iB5oQFnoECBcQAQ&url=http%3A%2F%2Frepository.unn.edu.ng%2Fbitstream%2Fhandle%2F123456789%2F9142%2FEgwu%2C%2520Patrick%2520Ejike%2520Jnr.pdf%3Fsequ.

[12] Akinyandenu, O. (2013). Counterfeit drugs in Nigeria: A threat to public health. African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 7(36), 2571–2576. https://doi.org/10.5897/ajpp12.343.

[13] Chinedu-Okeke, C. F., Okoro, N., & Obi, I. (2021). Mobile Authentication Service (MAS) Scheme and Public Participation in Eradicating Fake Drugs in Southeast Nigeria. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 05(06), 90–98. https://doi.org/10.47772/ijriss.2021.5605.

[14] Elizabeth Uzochukwu, C. (2017). Audience awareness and use of mobile authentication service (MAS) in identifying fake and substandard drugs in Nigeria. Journal of African Studies. Journal of African Studies, 77(11), 46–66.

[15] NAFDAC. (2010). The National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC) Mobile Authentication Service Scheme Guidelines for the Procurement and Management of the NAFDAC Mobile Authentication Service (MAS) Scheme. NAFDAC’s MAS Implementation Guide.

[16] Adekoya, H. O., & Ekeh, C. M. (2021). Awareness and Adoption of Drug Mobile Authentication Service : A Conscious Approach in Eradication of Fake and Counterfeit Drugs in Nigeria. 7(1), 43–51.

[18] Mhando, L., Jande, M. B., Liwa, A., Mwita, S., & Marwa, K. J. (2016). Public Awareness and Identification of Counterfeit Drugs in Tanzania: A View on Antimalarial Drugs. Advances in Public Health, 2016, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/6254157.

[19] Adisa, R., Adeniyi, O. R., & Fakeye, T. O. (2019). Knowledge, awareness, perception and reporting of experienced adverse drug reactions among outpatients in Nigeria. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 41(4), 1062–1073. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-019-00849-9.

[20] Adigwe, O. P., Onavbavba, G., & Wilson, D. O. (2022). Challenges Associated with Addressing Counterfeit Medicines in Nigeria: An Exploration of Pharmacists’ Knowledge, Practices, and Perceptions. Integrated Pharmacy Research and Practice, Volume 11(November), 177–186. https://doi.org/10.2147/iprp.s387354.

[21] Bansal, D., Malla, S., Gudala, K., & Tiwari, P. (2013). Anti-counterfeit technologies: A pharmaceutical industry perspective. Scientia Pharmaceutica, 81(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3797/scipharm.1202-03.

Viewed PDF 1535 33 -

Prevalence of Substance Use Disorders During the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study in Kanyama Township of Lusaka District, ZambiaAuthor: Steward MudendaDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art010

Prevalence of Substance Use Disorders During the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study in Kanyama Township of Lusaka District, ZambiaAuthor: Steward MudendaDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.11.03.Art010Prevalence of Substance Use Disorders During the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study in Kanyama Township of Lusaka District, Zambia

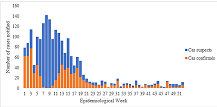

Abstract:

The coronavirus disease (Covid-19) pandemic has caused suffering and pain to mankind leading to many individuals practising self-medication and substance abuse that could elevate substance use disorders (SUDs). This study assessed the impact of Covid-19 on SUDs among Kanyama residents of Lusaka district, Zambia. We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study using patient files at Kanyama First-Level Hospital from September 2021 to October 2021. Data analysis was done using IBM SPSS version 26.0. Of the 101 participants, 86.1% were male. The study showed that Covid-19 had an impact on SUDs with alcohol (83.2%) being the most abused substance. There was no significant difference in the type of substances abused (p=0.870) and intoxication symptoms (p=0.331) between the pre-Covid and post-Covid groups. There was a significant difference between substance use (p=0.001) and withdrawal symptoms (p=0.002) in both cohorts, with the post-Covid group consuming more substances and experiencing more withdrawal symptoms. Factors that influenced substance abuse included recent unemployment (p<0.001), boredom (p<0.001), overcrowding at home (p<0.001), and gender-based violence (p<0.001) influenced the change in the pattern of substance use. Recreational use was not associated with a change in the pattern of substance abuse (p=0. 667). This study found that the Covid-19 pandemic increased the practices of substance abuse among Kanyama residents, especially those who were unemployed, bored, overcrowded at home and experienced gender-based violence. There is a need to heighten the monitoring and restriction of substance use, especially among adolescents and youths to curb some mental health problems.

Keywords: Covid-19; Pandemic; Self-medication; Substance abuse; substance use disorders; Zambia.Prevalence of Substance Use Disorders During the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study in Kanyama Township of Lusaka District, Zambia

References:

[1] Fournier, A.; Laurent, A.; Lheureux, F.; Ribeiro-Marthoud, M.A.; Ecarnot, F.; Binquet, C.; Quenot, J.P. Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Professionals in 77 Hospitals in France. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0263666, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263666.

[2] Joaquim, R.M.; Pinto, A.L.C.B.; Guatimosim, R.F.; de Paula, J.J.; Souza Costa, D.; Diaz, A.P.; da Silva, A.G.; Pinheiro, M.I.C.; Serpa, A.L.O.; Miranda, D.M.; et al. Bereavement and Psychological Distress during Covid-19 Pandemics: The Impact of Death Experience on Mental Health. Curr. Res. Behav. Sci. 2021, 2, 100019, doi: 10.1016/j.crbeha.2021.100019.

[3] Dawood, B.; Tomita, A.; Ramlall, S. ‘Unheard,’ ‘Uncared for’ and ‘Unsupported’: The Mental Health Impact of Covid -19 on Healthcare Workers in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0266008, doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0266008.

[4] Mudenda, S.; Chabalenge, B.; Matafwali, S.; Daka, V.; Chileshe, M.; Mufwambi, W.; Mfune, R.L.; Chali, J.; Chomba, M.; Banda, M.; et al. Psychological Impact of Covid-19 on Healthcare Workers in Africa, Associated Factors and Coping Mechanisms: A Systematic Review. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2022, 12, 518–532, doi:10.4236/AID.2022.123038.

[5] Pitlik, S.D. Covid-19 Compared to Other Pandemic Diseases. Rambam Maimonides Med. J. 2020, 11, e0027.

[6] Mudenda, S.; Mukosha, M.; Godman, B.; Fadare, J.O.; Ogunleye, O.O.; Meyer, J.C.; Skosana, P.; Chama, J.; Daka, V.; Matafwali, S.K.; et al. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Acceptance of Covid-19 Vaccines among Secondary School Pupils in Zambia: Implications for Future Educational and Sensitisation Programmes. Vaccines 2022, 10, 2141, doi:10.3390/VACCINES10122141.

[7] Etando, A.; Amu, A.A.; Haque, M.; Schellack, N.; Kurdi, A.; Alrasheedy, A.A.; Timoney, A.; Mwita, J.C.; Rwegerera, G.M.; Patrick, O.; et al. Challenges and Innovations Brought about by the Covid-19 Pandemic Regarding Medical and Pharmacy Education Especially in Africa and Implications for the Future. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1722, doi:10.3390/healthcare9121722.

[8] Kasanga, M.; Mudenda, S.; Gondwe, T.; Chileshe, M.; Solochi, B.; Wu, J. Impact of Covid-19 on Blood Donation and Transfusion Services at Lusaka Provincial Blood Transfusion Centre, Zambia. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 35, 74, doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.2.23975.

[9] Chileshe, M.; Mulenga, D.; Mfune, R.L.; Nyirenda, T.H.; Mwanza, J.; Mukanga, B.; Mudenda, S.; Daka, V. Increased Number of Brought-in-Dead Cases with Covid-19: Is It Due to Poor Health-Seeking Behaviour among the Zambian Population? Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 37, 136, doi:10.11604/pamj.2020.37.136.25967.

[10] Opanga, S.A.; Rizvi, N.; Wamaitha, A.; Abebrese Sefah, I.; Godman, B. Availability of Medicines in Community Pharmacy to Manage Patients with Covid-19 in Kenya; Pilot Study and Implications. Sch. Acad. J. Pharm. 2021, 10, 36–42, doi:10.36347/sajp. 2021.v10i03.001.

[11] Lee, A.M.; Wong, J.G.W.S.; McAlonan, G.M.; Cheung, V.; Cheung, C.; Sham, P.C.; Chu, N.M.; Wong, P.C.; Tsang, K.W.T.; Chua, S.E. Stress and Psychological Distress among SARS Survivors 1 Year after the Outbreak. Can. J. Psychiatry 2007, 52, 233–240, doi:10.1177/070674370705200405.

[12] Khalid, I.; Khalid, T.J.; Qabajah, M.R.; Barnard, A.G.; Qushmaq, I.A. Healthcare Workers Emotions, Perceived Stressors and Coping Strategies during a MERS-CoV Outbreak. Clin. Med. Res. 2016, 14, 7–14, doi:10.3121/cmr.2016.1303.

[13] Liu, X.; Kakade, M.; Fuller, C.J.; Fan, B.; Fang, Y.; Kong, J.; Guan, Z.; Wu, P. Depression after Exposure to Stressful Events: Lessons Learned from the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Epidemic. Compr. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 15–23, doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.02.003.

[14] Wu, P.; Liu, X.; Fang, Y.; Fan, B.; Fuller, C.J.; Guan, Z.; Yao, Z.; Kong, J.; Lu, J.; Litvak, I.J. Alcohol Abuse/Dependence Symptoms among Hospital Employees Exposed to a SARS Outbreak. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008, 43, 706–712, doi:10.1093/alcalc/agn073.

[15] Maunder, R.; Hunter, J.; Vincent, L.; Bennett, J.; Peladeau, N.; Leszcz, M.; Sadavoy, J.; Verhaeghe, L.M.; Steinberg, R.; Mazzulli, T. The Immediate Psychological and Occupational Impact of the 2003 SARS Outbreak in a Teaching Hospital. C. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2003, 168, 1245–1251.

[16] Maunder, R.G. Was SARS a Mental Health Catastrophe? Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2009, 31, 316–317.

[17] Chua, S.E.; Cheung, V.; McAlonan, G.M.; Cheung, C.; Wong, J.W.S.; Cheung, E.P.; Chan, M.T.; Wong, T.K.; Choy, K.M.; Chu, C.M.; et al. Stress and Psychological Impact on SARS Patients during the Outbreak. Can. J. Psychiatry 2004, 49, 385–390, doi:10.1177/070674370404900607.

[18] Jeong, H.; Yim, H.W.; Song, Y.J.; Ki, M.; Min, J.A.; Cho, J.; Chae, J.H. Mental Health Status of People Isolated Due to Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Epidemiol. Health 2016, 38, e2016048, doi:10.4178/epih. e2016048.

[19] Delanerolle, G.; Zeng, Y.; Shi, J.-Q.; Yeng, X.; Goodison, W.; Shetty, A.; Shetty, S.; Haque, N.; Elliot, K.; Ranaweera, S.; et al. Mental Health Impact of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, SARS, and Covid-19: A Comparative Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World J. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 739–765, doi:10.5498/wjp. v12.i5.739.

[20] Abramson, A. Substance Use During the Pandemic. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2021, 52, 22.

[21] Melamed, O.C.; Hauck, T.S.; Buckley, L.; Selby, P.; Mulsant, B.H. Covid-19 and Persons with Substance Use Disorders: Inequities and Mitigation Strategies. Subst. Abus. 2020, 41, 286–291, doi:10.1080/08897077.2020.1784363.

[22] Thiyagarajan, A.; James, T.G.; Marzo, R.R. Psychometric Properties of the 21-Item Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) among Malaysians during Covid-19: A Methodological Study. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 220, doi:10.1057/s41599-022-01229-x.

[23] Marzo, R.R.; Aye, S.S.; Naing, T.W.; Kyaw, T.M.; Win, M.T.; Soe, H.H.K.; Soe, M.; Kyaw, Y.W.; Soe, M.M.; Lin, N. Factors Associated with Psychological Distress among Myanmar Residents during Covid-19 Pandemic Crises. J. Public Health Res. 2021, 10, jphr.2021.2279, doi:10.4081/jphr.2021.2279.

[24] Marzo, R.R.; Ismail, Z.; Nu Htay, M.N.; Bahari, R.; Ismail, R.; Villanueva, E.Q.; Singh, A.; Lotfizadeh, M.; Respati, T.; Irasanti, S.N.; et al. Psychological Distress during Pandemic Covid-19 among Adult General Population: Result across 13 Countries. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Heal. 2021, 10, 100708, doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2021.100708.

[25] Marzo, R.R.; Villanueva, E.Q.; Faller, E.M.; Baldonado, A.M. Factors Associated with Psychological Distress among Filipinos during Coronavirus Disease-19 Pandemic Crisis. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 8, 309–313, doi:10.3889/oamjms.2020.5146.

[26] RilleraMarzo, R.; Villanueva, E.Q.; Chandra, U.; Htay, M.N.N.; Shrestha, R.; Shrestha, S. Risk Perception, Mental Health Impacts and Coping Strategies during Covid-19 Pandemic among Filipino Healthcare Workers. J. Public Health Res. 2021, 10, jphr.2021.2604, doi:10.4081/jphr.2021.2604.

[27] El-Abasiri, R.A.; Marzo, R.R.; Abdelaziz, H.; Boraii, S.; Abdelaziz, D.H. Evaluating the Psychological Distress of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic in Egypt. Eur. J. Mol. Clin. Med. 2020, 7, 1–12.

[28] Htay, M.N.N.; Marzo, R.R.; AlRifai, A.; Kamberi, F.; Radwa Abdullah, E.A.; Nyamache, J.M.; Hlaing, H.A.; Hassanein, M.; Moe, S.; Su, T.T.; et al. Immediate Impact of Covid-19 on Mental Health and Its Associated Factors among Healthcare Workers: A Global Perspective across 31 Countries. J. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 020381, doi:10.7189/jogh.10.020381.

[29] Htay, M.N.N.; Marzo, R.R.; Bahari, R.; AlRifai, A.; Kamberi, F.; El-Abasiri, R.A.; Nyamache, J.M.; Hlaing, H.A.; Hassanein, M.; Moe, S.; et al. How Healthcare Workers Are Coping with Mental Health Challenges during Covid-19 Pandemic? - A Cross-Sectional Multi-Countries Study. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Heal. 2021, 11, 100759, doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2021.100759.

[30] Marzo, R.R.; Singh, A.; Mukti, R.F. A Survey of Psychological Distress among Bangladeshi People during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Heal. 2021, 10, 100693, doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2020.100693.