Table of Contents - Issue

Recent articles

-

Causes of Reduced Revenue Generation in Federal Staff Hospital (Fsh) Laboratory; Annex 111 Federal Capital Territory, AbujaAuthor: Bassey, G. MDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art001

Causes of Reduced Revenue Generation in Federal Staff Hospital (Fsh) Laboratory; Annex 111 Federal Capital Territory, AbujaAuthor: Bassey, G. MDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art001Causes of Reduced Revenue Generation in Federal Staff Hospital (Fsh) Laboratory; Annex 111 Federal Capital Territory, Abuja

Abstract:

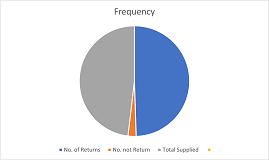

The healthcare delivery system has been criticized for its “culture of blame” in which culpability for failure has been attributed to the human elements of the system: The Study was designed to identify and ascertain reasons for low-revenue generation in Federal staff hospital (FSH) laboratory; annex 111, Abuja and to proffer solutions, as well as deliver health care that minimizes risks and harm to service users, including avoiding preventable injuries and reducing medical errors. According to World Health Organization (WHO), a well-functioning healthcare system requires a financing mechanism, well trained and adequately paid workforce, reliable Information on which to base decisions and policies, and well-maintained health facilities to deliver quality services and technologies. Out of a total number of two hundred (200) respondents interviewed using questionnaires, hundred and sixty (160) were received using the random sampling method. 41% of the respondents believed that there are no barriers to accessing the facility, 48.0% indicated a Lack of Knowledge, and 11.0% said proximity. The year 2017/2018 to 2019 report showed a tremendous improvement. Revenue generated and the number of patients for the year 2018 was to the tune of twenty-nine million, nine hundred and seventy-six thousand, six hundred and sixty naira only (₦29,976,660.00) and twelve thousand, seven hundred and twenty-six patients (12,726) respectively. In comparing the year 2017/2018, respectively, this Study concluded that for overall improvement of the quality and performance in the healthcare environment, there is a need for the development of new inter-organizational patterns of care delivery and complex multitier governance structures.

Keywords: Federal staff hospital (FSH) laboratory, Health care, Knowledge. Preventable injuries, World Health Organization (WHO).Causes of Reduced Revenue Generation in Federal Staff Hospital (Fsh) Laboratory; Annex 111 Federal Capital Territory, Abuja

References:

[1] Carter JY:(1999), Role of laboratory services in health care, The present status in Eastern Africa and recommendations for future. East Afr Med J,73(70) (editorial).

[2] W.C. Cockerham, (2008) B.P. Hinote, in International Encyclopedia of Public Health.

[3] Gemson, G. S., & Kyamru, J. I. (2013). Theory and practice of research methods for the health and social sciences (Rev ed). Jalingo: Livingstone Education Publishing Enterprise (Nig).

[4] Global One Logistics, LLC. (2010). Retrieved from http://www.theymustthinkwerecrazy.com/.

[5] Robert M. Califf, (2018), Principles and Practice of Clinical Research (Fourth Edition).

[6] International Development Research Centre. (2018, July 19). Getting the healthcare basics right for pregnant women in Nigeria. https://www.idrc.ca/en/research-in-action/getting-healthcare-basics-right-pregnant-women-Nigeria.

[7] Rocha, V. (2019), How telehealth can get healthcare to more people. Retrieved June 4, 2020, from weforum.org.

[8] Kassu A, Aseffa A:(1999) Laboratory services in health center within Amhara region, north Ethiopia. East Afr Med J.76(5):239-242.

[9] Abdosh B: (2006) The quality of hospital services in Eastern Ethiopia: patient’s perspective. Ethiop J Health Dev.2006,20(3) :199-200.

[10] TsankovaG. Georgieva E., Kaludova, V, Ermenlieva N. :(2014) Patients Satisfaction with laboratory services at selected medical diagnostic laboratories in Varna. J IMAB. ;20(2):500-501.

[11] Jeffrey R. Balser, William W. Stead, in The Transformation of Academic Health Centers, 2015

[12] Aregbesola, B. S. (2018). Prioritizing Health for the Benefit of the Populace – A Perspective from Nigeria., Global Health, Social Issues, June 15.

[13] Hoyle, David (2005). ISO 9000 Quality Systems Handbook, Fifth Edition. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 686. ISBN 978-0-7506-6785-2.

[14] http://www.drsforamerica.org/learn/policy-center/healthcare-delivery-system.

[15] Laszeray, Tech, (2019), The importance of quality management systems. 12315 York Delta Drive, North Royalton, OH 44133, inquiry@laszeray.440-517-7822.

[16] Tricker, Ray (2005). ISO 9001:2000 Audit Procedures, Second Edition. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-7506-6615-2.

[17] Dobb, Fred (2004). ISO 9001:2000 Quality Registration Step-by-Step, Third Edition. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-7506-4949-0.

[18] Hoveland I, (2005.) Successful communication: a toolkit for researchers and civil society organizations. Rapid research and policy development; https://www.odi.org/publications/155-successfulcommunication.

[19] Ochei, O.J., Kolhatkar., (2007), Medical Laboratory Science, Theory and Practice, Tata McGraw-Hill Publishing Company Limited, New Delhi, page 111-151.

[20] Hassemer DJ:(2003), Wisconsin State laboratory of Hygiene’s role in clinical laboratory improvement. Wis Med J.102 (6):56-59.

[21] Oja PI, Kouri TT,Pakarinen AJ:(2006), From customer satisfaction survey to corrective actions in laboratory services in a University hospital .Int J Qual Health Care.18(6): 422-428 10.1093/intqhc/mz1050.

Viewed PDF 971 46 -

Factors Contributing to Lost to Follow up on People Living with HIV, Bor State HospitalAuthor: John Aban Chol NyijokDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art002

Factors Contributing to Lost to Follow up on People Living with HIV, Bor State HospitalAuthor: John Aban Chol NyijokDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art002Factors Contributing to Lost to Follow up on People Living with HIV, Bor State Hospital

Abstract:

Long-term regular follows up of ART clients is an important component of HIV care, treatment, and prevention. Clients who are lost to follow-up while on treatment compromise their own health leading to poor treatment outcomes, which has a negative impact on HIV control programs. This study aimed to determine the factors contributing to the lost to follow-up (LTFU) of HIV clients on ARVs at the ART clinic, Bor state hospital. A retrospective cohort study of 60 people living with HIV from 576 clients who are lost to follow-up and attending an ART clinic service between Jan. 2015 - Dec. 2019 was undertaken. LTFU was defined as not taking an ARVs drug refill for a period of three months or longer from the last attendance for refill and not yet classified as ‘died’ or ‘transferred out. A total of 1993 clients enrolled at the HIV ART clinic, a total of 576 clients (29.0%) were defined as LTFU from enrolled clients, and 1417 clients (71.0%) were actively being followed up and on ART in the HIV ART clinic. Overall, these data suggested that LTFU in this study was high in patients who were married, low level of education, stigma-related factors, unemployment among clients, and clinical stages I &II were associated with LTFU in this study.

Keywords: Anti-retroviral therapy, ART, factors contributed to lost to follow up, HIV, lost to follow up, PLHIV, South Sudan.Factors Contributing to Lost to Follow up on People Living with HIV, Bor State Hospital

References:

[1] atilda K, Esther B, Joy K, et al. Loss to Follow-Up among HIV Positive Pregnant and Lactating Mothers on Lifelong Anti-retroviral Therapy for PMTCT in Rural Uganda.

[2] Bryan E. Shepherd, Meridith B, Lara M. E. Vaz, et al. Impact of Definitions of Loss to Follow-up on Estimates of Retention, Disease Progression, and Mortality: Application to an HIV Program in Mozambique, American Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 178, Issue 5, 1 September 2013, Pages 819–828, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt030.

[3] Chi BH, Yiannoutsos CT, Westfall AO, et al. (2011) Universal Definition of Loss to Follow-Up in HIV Treatment Programs: A Statistical Analysis of 111 Facilities in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. PLoS Med 8(10): e1001111. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001111.

[4] Opio, D., Semitala, F.C., Kakeeto, A. et al. Loss to follow-up and associated factors among adult people living with HIV at public health facilities in Wakiso district, Uganda: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res 19, 628 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4474-6.

[5] Faraz A, Gideon M, Joseph S. et al. Identifying and Reengaging Patients Lost to Follow-Up in Rural Africa: The “Horizontal” Hospital-Based Approach in Uganda. Global Health: Science and Practice March 2019, 7(1):103-115; https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-18-00394.

[6] Williams H, Filbert F, Brouno P. et al. Lost to follow up and clinical outcomes of HIV adult patients on anti-retroviral therapy in care and treatment centers in Tanga City, north-eastern Tanzania. Tanzania Journal of Health Research Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/thrb.v14i4.3 Volume 14, Number 4, October 2012.

[7] MOH. Fact sheet on the Uganda Population HIV Impact Assessment [Internet]. WHO | Regional Office for Africa. 2017 [cited 2018 Aug 21]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/fact-sheet-ugandapopulation-hiv-impact-assessment.

[8] Bior, Awak Deng. HIV/AIDS: A Threat to National Security in South Sudan. Sudd Institute, 2014, www.jstor.org/stable/resrep11027 Accessed 26 July 2020.

[9] Opio, D., Semitala, F.C., Kakeeto, A. et al. Loss to follow-up and associated factors among adult people living with HIV at public health facilities in Wakiso district, Uganda: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res 19, 628 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4474-6.

[10] Kiwanuka J, Mukulu Waila J, Muhindo Kahungu M, et al. Determinants of loss to follow-up among HIV positive patients receiving anti-retroviral therapy in a test and treat setting: A retrospective cohort study in Masaka, Uganda. PLoS One. 2020; 15(4): e0217606. Published 2020 Apr 7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217606.

[11] Geng EH, Bangsberg DR, Musinguzi N, et al. Understanding reasons for and outcomes of patients lost to follow-up in anti-retroviral therapy programs in Africa through a sampling-based approach. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010; 53(3):405-411. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b843f0.

[12] Vervölgyi, E., Kromp, M., Skipka, G. et al. Reporting of loss to follow-up information in randomised controlled trials with time-to-event outcomes: a literature survey. BMC Med Res Methodol 11, 130 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-130.

[13] Frédérique C, Kathrin Z, Olivia K, et al. Outcomes of Patients Lost to Follow-up in African Antiretroviral Therapy Programs: Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 67, Issue 11, 1 December 2018, Pages 1643–1652, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy347.

[14] Zürcher K, Mooser A, Anderegg N, et al. Outcomes of HIV-positive patients lost to follow-up in African treatment programmes. Trop Med Int Health. 2017; 22(4):375-387. doi:10.1111/tmi.12843In.

[15] Kaplan S, Nteso KS, and Ford N, et al. Loss to follow-up from anti-retroviral therapy clinics: A systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies in South Africa from 2011 to 2015. South Afr J HIV Med. 2019; 20(1):984. Published 2019 Dec 18. doi:10.4102/sajhivmed. v20i1.984in 16 –.

[16] Goggin K, Hurley EA, Staggs VS, et al. Rates and Predictors of HIV-Exposed Infants Lost to Follow-Up during Early Infant Diagnosis Services in Kenya. AIDS Patient Care STDS, 33(8):346-353, 01 Aug 2019.

[17] World Health Organisation (2008), Mortality of Patients Lost to follow-up in Antiretroviral Treatment Programs in Resource limited setting. System review and Meta-Analysis. Available at (www.plosone.org/./info:doi/2F10.137).

[18] World Health Organisation (2008), Lost opportunity to complete CD4+ Lymphocytes testing among patients who tested positive for HIV in South Africa. Lost Opportunities to initiate HIV Care in South Africa. Available at (www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/88/9/09-068981.pdf).

[19] Center for Disease Control and Prevention CDC (2015), How HIV passed from one person to another. Available at (www.cdc.gov/hiv/./qa/transimissi).

[20] PLHIV (2010), Publication for People Living with HIV/AIDS. Available at (www.nephark.org).

[21] Rebecca Hodes, nam-aidmap(2010). Lost to follow-up health system failure, not patients to blame. 8th International AIDS Conference, 29th July 2010. Available at (www.aidsmap.com/loss-to-follow-up-he).

[22] Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (2011), HIV in general. Available at (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hiv).

[23] Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (2006, 2010, 2011). Overview of the global AIDS Epidemic. UN Report on the Global AIDS epidemic. Available at (www.unaids.org/globalreport/global).

[24] International HIV/AIDS charity (2011). Averting HIV/AIDS. Available at (www.avert.org/world-aids-day.htm).

[25] Geng EH, Bangsberg DR, MUSNGUZIN (2009). Understanding reasons for and outcomes of patients lost to follow-up in anti-retroviral therapy programs in Africa through a sampling-based approach. J Acquir Immune Defic. Syndr. 2009 Sept.10.

[26] Lessels, R.J.; Mutevendzi, P.C.; Cooke, G.S.; Nowel M.L.; Retention in HIV Care for individuals not yet eligible for anti-retroviral therapy: rural KwanZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic. Syndr 2010.

[27] Paula Braitsein (2010). XVIII International AIDS Conference of 2010. Available at (www.aids2010.org/).

[28] Cohort profile: The International epidemiological databases to evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int J. Epidemiol (2011): dyr080vldy08.

[29] Amref ART hub (2011). Definition of LTFU in Pre-ART and ART. Amref ART knowledge Hub. Available at (www.hub.amref.org/index.php).

[30] Dr. Benjamin H.C.; Ronald A.C.; Albert M.; Andrew O.; Westfall.; Wilbrand M.; Mohammed L.; Lloyd B.M.; Stenttet V.; Jeffrey S.A.; A.M J Epidemiol.2010 April 15;171(8):924-931. Published online 2010 March. 10. d0i:10.1093 /aje/kw9008.

[31] Gilles V.C.; Nathan F.; Katherine H.; Eric G.; Shaheed M.; David C.; Andrew B.: PLOS ONE (2011). vol.6, issue 2; Published online 2011. Public library of science pg 9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014684. Available at (www.embase.com).

Viewed PDF 911 85 -

Utilization of Community-Based Health Insurance among Residence of Katsina State, NigeriaAuthor: Yahaya Shamsuddeen SuleimanDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art003

Utilization of Community-Based Health Insurance among Residence of Katsina State, NigeriaAuthor: Yahaya Shamsuddeen SuleimanDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art003Utilization of Community-Based Health Insurance among Residence of Katsina State, Nigeria

Abstract:

Enrollment into any form of insurance is very low in Katsina State, with most people paying out of pocket for health care. The utilization of community-based health insurance will provide financial risk protection and improve health outcomes. The objective of the study is to compare differences in Utilization between community-based health insurance member households and non-member households and to identify factors associated with the utilization. A comparative cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted among household heads in Katsina State, Nigeria. Targeted participants were selected using multistage sampling techniques. Primary data was generated using Open Data Kit (ODK), which was later downloaded and exported to SPSS version 20® for statistical analysis. Mean, and standard deviation from the mean (Mean ± SD) were used to study population characteristics towards utilization of CHI. The statistical significance level of analyzed variables were accepted at P≤0.05. The mean age of respondents was 46.82±13 and 44±12.5 years for CBHI enrolled and non-ensured groups, respectively. Heads of the households were predominantly males and currently married, with 97.3% and 93.3% for CBHI members compared to 82.7% and 99.3% of non-member households, respectively. The enrolled CBHI group utilizes PHC services more than the non-enrolled group(p<0.05) with age, marital status, education, number of children, and distance to health facilities all associated with Utilization. Utilization of CBHI was higher among enrolled groups than non-enrolled groups. Many factors, such as age, marital status, education level, and Payment of transportation to the facility, affect utilization of these services. We recommend CBHI be expanded, poor and vulnerable groups are given special consideration, and people not enrolled should be encouraged to join.

Keywords: Community, Comparative, Health, Insurance, Utilization.Utilization of Community-Based Health Insurance among Residence of Katsina State, Nigeria

References:

[1] Carrin, G. (2003). Community-based Health Insurance Schemes in Developing Countries; facts, problems, and perspectives. World Health Organization, Geneva.

[2] The World Health Report; Health System Financing; The Path to Universal Coverage, 2010, http://www.who.int/whr/2010/whr10_en.pdf Accessed 2 nd August 2020.

[3] WHO 2020 Community-Based Health insurance Scheme. https://www.who.int/news-room/factsheets/detail/community-based-health-insurance2020.

[4] Onwujekwe.O, Valenyi. E. Feasibility of voluntary health insurance in Nigeria. 2006. The World Bank.

[5] National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). 2017 Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2016-17, Survey Findings Report. Abuja, Nigeria; National Bureau of Statistics and United Nations Children’s Fund.

[6] Nasiru, L., Mohammed, T.S., Hassan, A., Shamsuddeen, Y (2021). Health Care Access and Utilization among Households in Katsina State North-western, Nigeria. International Journal of Tourism and Hotel Management; 2641-6948.

[7] Yahaya S.S, Mustapha M, , Lawal N , Runka JY. Knowledge of Community Based Health Insurance among Residence of Katsina State, Nigeria; A Comparative Cross-Sectional Study. Texila International Journal of Academic Research Special Edition Apr 2022.

[8] Araoye MO. Research Methodology with Statistics for Health and Social Sciences, first edition. Nathadex publishers Ilorin, 2004;25- 120.

[9] Gnawali DP, Pokhrel S, Sié A, Sanon M, De Allegri M, Souares A, Dong H, Sauerborn R. The effect of community-based health insurance on the utilization of modern health care services; evidence from Burkina Faso. Health Policy. 2009 May;90(2-3);214-22. doi; 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.09.015. Epub 2008 Nov 25. PMID; 19036467.

[10] Asmamaw Atnafu Tsegaye Gebremedhin. Community-Based Health Insurance Enrollment and Child Health Service Utilization in Northwest Ethiopia; A Cross-Sectional Case Comparison Study. Clinico Economics and Outcomes Research 2020;12.

[11] Atnafu A, Gebremedhin T. Community-Based Health Insurance Enrolment and Child Health Service Utilization in Northwest Ethiopia; A Cross-Sectional Case Comparison Study. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2020 Aug 10;12;435-444. doi; 10.2147/CEOR.S262225. PMID; 32848434; PMCID; PMC7428314.

[12] Sarah Alkenbrack, Magnus Lindelow. The impact of community-based health insurance on utilization and out-of-pocket expenditures in Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Health Econ. 2015 Apr;24(4);379-99.

[13] Bayked EM, Kahissay MH,Workneh BD. Factors affecting the uptake of community-based health insurance in Ethiopia; a systematic review. Int J Sci Rep 2021;7(9);459-67. (5) (PDF) Factors affecting community based health insurance utilization in Ethiopia; A systematic review. Available from: https;//www.researchgate.net/publication/340193552_Factors_affecting_community_based_health_insurance_utilization_in_Ethiopia_A_systematic_review [accessed May 20 2022].

Viewed PDF 2167 73 -

Assessment of the Nutritional Status of Babies with Neonatal Jaundice in GhanaAuthor: Frederick AdiibokaDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art004

Assessment of the Nutritional Status of Babies with Neonatal Jaundice in GhanaAuthor: Frederick AdiibokaDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art004Assessment of the Nutritional Status of Babies with Neonatal Jaundice in Ghana

Abstract:

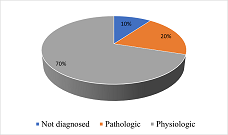

Neonatal jaundice is a public health concern responsible for a relatively high rate of infant morbidity and mortality. Therefore, it is prudent to put in place effective risk-reduction strategies and detect and treat new born jaundice effectively. Optimum nutrition has been shown to be crucial to health and well-being. This study, therefore, sought to investigate the nutritional status of babies that report to three referral hospitals in Ghana (Korle-bu Teaching Hospital, Greater Accra Regional Hospital and the Tamale Teaching hospital). It was a multi-center nested, case-control study involving 120 cases and 120 controls of neonates in the three referral hospitals in Ghana. The study revealed that babies with neonatal jaundice in Ghana mostly have a normal nutritional status, even though they lose about 5% of their birth weight. More mothers of healthy babies (88.3%) did exclusive breastfeeding, compared with mothers of babies with neonatal jaundice (76.7%). It was also revealed that the three referral hospitals implemented the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative’s ten steps to successful breastfeeding as a measure to prevent suboptimal feeding, which could lead to an increase in bilirubin levels. Assessment and interventions to prevent weight loss should therefore be paramount for babies with neonatal jaundice.

Keywords: Malnutrition, Neonatal jaundice.Assessment of the Nutritional Status of Babies with Neonatal Jaundice in Ghana

References:

[1] Wickström, R., Skiöld, B., Petersson, G., Stephansson, O., Altman, M. (2018). Moderate neonatal hypoglycemia and adverse neurological development at 2-6 years of age. European Journal of Epidemiology, 33, 1011–1020.

[2] American Academy of Pediatrics (2004). Management of hyperbilirubinemia in the new-born infant 35 or more weeks of gestation. Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia. Pediatrics, 114(1), 297-316.

[3] Hoynes, H., Schanzenback, D.W. & Almond, D. (2016). Long-run impacts of childhood access to the safety net. American Economic Review, 106(4), 903-934.

[4] Radhakrishnan, K. (2015). Vitamin D deficiency in children: Is your child getting enough? U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved from: http://health.usnews.com/health-news/patient-advice/articles/2015/11/06/vitamin-d-deficiency-in-children.

[5] Benson, S.L.J., Thompson, M. (2016). Nutrition assessment. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Pocket Guide to Neonatal Nutrition, 2nd Edn. Chicago. Pp. 1-31.

[6] Leppanen, M., Lapinleimu, H., Lind, A., et al. (2014). Antenatal and postnatal growth and 5-year cognitive outcome in very preterm infants. Pediatrics, 133(1), 63-70. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1187.

[7] Corkins, M.R. (2017). Why is diagnosing pediatric malnutrition important? Nutrition Clinical Practice, 32(1), 15-18. doi: 10.1177/0884533616678767.

[8] Mehta S, Kumar P, Narang A. (2005). A randomized controlled trial of fluid supplementation in term neonates with severe hyperbilirubinemia. Journal of Pediatrics, 147(6), 781-785.

[9] Weng, Y., Chiu, Y., Cheng, S. (2012). Breast Milk Jaundice and Maternal Diet with Chinese Herbal Medicines. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Retrieved from https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2012/150120/ on 18th April 2017.

[10] Wilde, V.K. (2021). Breastfeeding Insufficiencies: Common and Preventable Harm to Neonates. Cureus, 13(10), e18478. doi:10.7759/cureus.18478.

[11] Metcoff, J. (1994). Clinical assessment of nutritional status at birth. fetal malnutrition and SGA are not synonymous. Pediatric Clinical North America, 41(5), 875-91.

[12] Althomali, R., Aloqayli, R., Alyafi, B., Nono, A., Alkhalaf, S., Aljomailan, A., et al. (2018). Neonatal jaundice causes and management. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 5, 4992-6.

[13] Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine (ABM) (2017). ABM Clinical Protocol #22: Guidelines for Management of Jaundice in the Breastfeeding Infant 35 Weeks or More of Gestation. Vol., 12, No. 5. DOI: 10.1089/bfm.2017.29042.vjf.

[14] Koletzko, B. (2015). Pediatric Nutrition in Practice; World Review Nutrition Dietetics: Basel, Karger. Volume 113, pp. 139–146.

[15] Hunt, L., Ramos, M., Helland, Y., Lamkin, K. (2020). Decreasing neonatal jaundice readmission rates through implementation of a jaundice management guide. BMJ Open Qual, 9, 1.

[16] Bolajoko, O. Olusanya, M., Kaplan, T., Hansen W. R, (2018). Neonatal hyperbilirubinaemia: a global perspective. Lancet Child Adolescent Health 4642(18), 30139-1 Retrieved on 4th June 2021 from http://www.thelancet.com/child-adolescent.

[17] Pagana, K.D., Pagana, T.J., Pagana, T.N. (2019). Mosby’s Diagnostic and Laboratory Test Reference. 14th ed. Mo: Elsevier, St. Loius.

[18] Escobar, G., Gonzales, M., Armstrong, M.A., Folck, B.F., Xiong, B., Newman, T.B. (2002). Rehospitalisation for neonatal dehydration: A nested case-control study. Arch Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 156, 155-161.

[19] Boo N.Y. and Lee, H.T. (2002). Randomized controlled trial of oral versus intravenous fluid supplementation on serum bilirubin level during phototherapy of term infants with severe hyperbilirubinaemia. Journal of Paediatric Child Health, 38(2), 151-155.

[20] Thornton, P.S., Stanley, C.A., De Leon, D.D, et al. Recommendations from the pediatric endocrine society for evaluation and management of persistent hypoglycemia in neonates, infants, and children. Journal of Pediatrics, 2015;167:238–245.

Viewed PDF 1194 40 -

Managing Municipal Solid Waste Issues; Sources, Composition, Disposal, Recycling, and Volarization, Chililabombwe District, ZambiaAuthor: Gift SakanyiDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art005

Managing Municipal Solid Waste Issues; Sources, Composition, Disposal, Recycling, and Volarization, Chililabombwe District, ZambiaAuthor: Gift SakanyiDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art005Managing Municipal Solid Waste Issues; Sources, Composition, Disposal, Recycling, and Volarization, Chililabombwe District, Zambia

Abstract:

Solid waste continues to pose important challenges to our environment on a daily basis. Insufficient solid waste management systems and equipment have contributed to the alteration to the ecosystems, including water, air, and soil pollution that infringes on the health of the general public that is associated with health ailments like cholera and other food and water borne diseases. Chililabombwe district’s face has continued to be dented with the unkempt environment with littered solid waste that has become a stinging and widespread challenge, especially in the urban areas of the district. Solid waste (SW) collection and working disposal systems are the major problems of the urban environment in most developing countries worldwide. MSW management solutions are financially dependable for the technical viable, socially inclement, and legally accepted. Solid waste management remained the biggest challenge that all the local authorities in Zambia and many developing countries in Africa. Commercialization or valorization of organic food waste was one of the important research areas that could combat the increased solid waste in the environmental causing environmental degradation. The objective of this study was to address matters that would respond positively to the waste management crisis in the district. As waste continues to be accumulated, with its high generation, more technologies are sought in the area of treatment and exploitation of organic and municipal waste through composting and anaerobic digestion in the management of waste. The lack of technologies and machinery has equally downplayed the essence of waste management in the Chililabombwe district.

Keywords: Anaerobic, Digestion, Landfill, Organic, Solid wastes, Valorization.Managing Municipal Solid Waste Issues; Sources, Composition, Disposal, Recycling, and Volarization, Chililabombwe District, Zambia

References:

[1] Ayomoh M, Oke S, Adedeji W and Charles-Owaba O (2008) An approach to tackling the environmental and health impacts of municipal solid waste disposal in developing countries. Journal of Environmental Management 88(1); 108–114.

[2] McDougall, F., White, P., Franke, M., & Hindle, P. (2011). Integrated Solid Waste Management, A Life-Cycle Inventory. London; Blackwell Science.

[3] Environmental Management Act (No.12 of 2011 section 56(1)(a)(b) &(c) of the Laws of Zambia.

[4] GRZ. (2017). Environmental Management and Coordination (Waste management Regulations). Lusaka; GRZ.

[5] BlaserF.Schluep.M.2012E-waste. Economic Feasibility of e-Waste Treatment in Tanzania Final Version, March 2012. EMPA Switzerland & UNIDO.

[6] Wilson D.C et al.,2010Comparative Analysis of Solid Waste Management. In Cities Around the World. Paper Delivered at the UK Solid Waste Association, Nov.2010.

[7] Okot-OkumuJ.NyenjeR.2011 Municipal solid waste management under decentralisation in Uganda.” Habitat International 35, 537.

[8] Sarkhel, P. & S. Banerjee. 2009. Municipal solid waste management, source-separated waste, and stakeholder’s attitude; a contingent valuation study. Environment, Development, and Sustainability.

[9] Macawife, J. & G. S. Su. 2009. Local government officials’ perceptions and attitudes towards solid waste management in Dasmarinas, Cavite, Philippines. Journal of Applied Sciences in Environmental Sanitation 4; 63-69.

[10] Sharholy, M., Ahmad, K., Mahmood, G., and Trivedi, R.C. (2008) Municipal Solid Waste Management in Indian Cities. Waste Management, 28, 459-467. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2007.02.008.

[11] Antipolis S (2000) Syria profile. In Policies and Institutional Assessment of Solid Waste Management in Five Countries. Blue Plan Regional Activity Centre, Valbonne, France.

[12] Al-Khatib IA, Arafat HA, Basheer T et al. (2007) Trends and problems of solid waste management in developing countries; a case study in seven Palestinian districts. Waste Management 27(12); 1910–1919.

[13] Bandara NJ, Hettiaratchi JPA, Wirasinghe S and Pilapiiya S 2007 Relation of waste generation and composition to socio-economic factors; a case study. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 135(1–3); 31–39.

[14] Al-Khatib IA, Monou M, Zahra ASFA, Shaheen HQ and Kassinos D (2010) Solid waste characterization, quantification, and management practices in developing countries. A case study; Nablus district–Palestine. Journal of Environmental Management 91(5); 1131–1138.

[15] C. Zurbrugg, S. Drescher, I. Rytz, A. H. M. M. Sinha, and I. ¨ Enayetullah, “Decentralised composting in Bangladesh, a win-win situation for all stakeholders,” Resources, Conservation and Recycling, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 281–292, 2005.

[16] Mbewe, R., & Mundia, Y. (2012). National Study on Health Care waste, Ministry of Health. Lusaka; CBoH.

[17] Asase M, Yanful EK, Mensah M, Stanford J and Amponsah S (2009) Comparison of municipal solid waste management systems in Canada and Ghana; a case study of the cities of London, Ontario, and Kumasi, Ghana. Waste Management 29 (10); 2779–2786.

[18] Nthambi, M. (2013). An Economic Assessment of Household Solid Waste Management Options; The Case of Kibera Slum, Nairobi City, Kenya. Nairobi; University of Nairobi.

[19] Al-Yousfi B (2004) Sound Environmental Management of Solid Waste – the Landfill Bioreactor. United Nations Environmental Programme – Regional Office for West Asia, Manama, Bahrain

[20] Nyang’echi, G. N. (2012). Management of Solid and Liquid wastes. A Manual for Environmental Health Workers. African Medical Research Foundation.

[21] GRZ. (2011). Ministry of Planning, National Development and Vision 2030 Progress Report. Lusaka; GRZ.

[22] Almasri R, Muneer T and Cullinane K (2011) The effect of transport on air quality in urban areas of Syria. Energy Policy 39(6); 3605–3611.

[23] L. Dahlén Household Waste Collection Factors and Variations, Department of Civil, Mining and Environmental Engineering Division of Waste Science.

[24] Calo F and Parise M (2009) Waste management and problems of groundwater pollution in karst environments in the context of a post-conflict scenario; the case of Mostar (Bosnia Herzegovina). Habitat International 33(1); 63–72.

[25] Batool SA and Ch MN (2009) Municipal solid waste management in Lahore city district, Pakistan. Waste Management 29(6); 1971–1981.

[26] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Wastes – Non-Hazardous Waste – Municipal Solid Waste, 1200 Pennsylvania Ave., N. W. Washington, DC 20460, U.S.A. (2013).

[27] S. H. Swan, “Environmental phthalate exposure in relation to reproductive outcomes and other health endpoints in humans,” Environmental Research, vol. 108, no. 2, pp. 177–184, 2008.

[28] M. P. Velez, T. E. Arbuckle, and W. D. Fraser, “Female exposure ´ to phenols and phthalates and time to pregnancy; The Maternal-Infant Research on Environmental Chemicals (MIREC) study,” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 103, no. 4, pp. 1011.e2–1020.e2, 2015.

[29] I.A. Al-Khatib M. Monou S.F. Abdul Q.S. Hafez K. Despo Solid waste characterization, quantification, and management practices in developing countries. A case study Nablus district – Palestine 2010.

[30] Mashamba, S. M. (2015). Slum Development; A Manifestation on the failed public housing delivery system, Lusaka; Department of Physical Planning and Housing, Zambia.

[31] Laner, D., Fellner, J., Brunner, & P.H. (2009a). Flooding of municipal solid waste landfills - An environmental hazard? Science of the Total Environment, 407, 3674–3680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.03.006.

[32] Chalmin P and Gaillochet C (2009) From Waste to Resource, an Abstract of World Waste Survey 2009. Cyclope, Veolia Environmental Services, Edition Economica, Aubervilliers, France.

[33] Chowdhury M (2009) Searching quality data for municipal solid waste planning. Waste Management 29(8); 2240–2247.

[34] Kumar, H. D. (2008). Environmental Pollution and Waste Management. MD Publications Ltd.

[35] Larkin, G. R. (2014). Public-private partnerships in economic development; A review of theory and practice. Economic Development Review, 7-9.

[36] Williams, P.W., ed., 1993, Karst Terrains, Environmental Changes and Human Impact; Cremingen-Destedt, Germany, Catena Supplement no. 25, 268 p.

Viewed PDF 1495 73 -

Systemic Effects on Access to and Utilization of Quality Contraceptive Services by Women of Reproductive age During Covid-19 Pandemics in Oyo State, NigeriaAuthor: Esther OyewoDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art006

Systemic Effects on Access to and Utilization of Quality Contraceptive Services by Women of Reproductive age During Covid-19 Pandemics in Oyo State, NigeriaAuthor: Esther OyewoDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art006Systemic Effects on Access to and Utilization of Quality Contraceptive Services by Women of Reproductive age During Covid-19 Pandemics in Oyo State, Nigeria

Abstract:

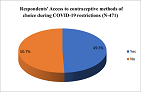

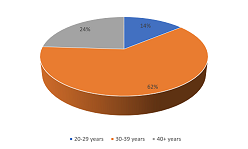

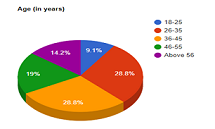

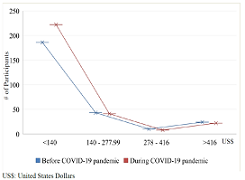

The indirect health impacts include diversion or depletion of resources to provide routine care and decreased access to routine care resulting from an inability to travel due to restriction, fear, or other factors. This paper presents the findings of a cross-sectional quantitative study exploring systemic effects on access to and utilization of quality contraceptive services by women of reproductive age during the Covid-19 pandemic in Oyo State, Nigeria. A purposive sampling technique was used to select 471 users of users of MNCH services (postnatal clinic and family planning services and immunization uptakes) that responded to 43 structured questionnaires that included socio-demographical characteristics, knowledge of contraceptive products and service availability, contraceptive supplies, access and utilization, health system opportunities and challenges amidst Covid-19 pandemics. Of the 471 respondents, the mean age of respondents was 29.63± 3.29years, with (34.2%) within 26-30 years age group. Majorly self-employed/business (74.9%), (91.1%) Yorubas ethnicity. Only 49.2% accessed contraceptive services during restrictions; due to overwhelming fear of Covid-19 by (31.7%), and disruption of services (31.1%). Others mentioned cost, restriction in movement, and difficulty in seeing caregivers. With 65.4% of the total respondents currently obtained a method with easy in restrictions. The Chi-square test, on the relationship between respondents’ access to and utilization of contraceptive services with systemic factors shows a significant relationship with p =0.004 during the pandemic. It becomes highly imperative that the family planning program be redesigned to improve the health system as part of the preparedness measures to address gaps due to the Covid-19 restrictions.

Keywords: Access and Utilization, Contraceptives, Covid-19 Pandemic, Effects, Systemic.Systemic Effects on Access to and Utilization of Quality Contraceptive Services by Women of Reproductive age During Covid-19 Pandemics in Oyo State, Nigeria

References:

[1] Zulu JM, et al, 2015. Innovation in health service delivery: integrating community health assistants into the health system at the district level in Zambia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):1.

[2] Schneider H, Lehmann U, 2016. From Community Health Workers to Community Health Systems: Time to Widen the Horizon? Health Syst Reform;2(2):112–8.

[3] Vinit Sharma et al., 2020Why the Promotion of Family Planning Makes More Sense Now Than Ever Before? First Published August 5, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1177/0972063420935545.

[4] Purdy C, 2020. Opinion: How will Covid-19 affect global access to contraceptives—and what can we do about it? Devex, https://www.devex.com/news/sponsored/opinion-how-will-covid-19-affect-global-access-to-contraceptives-and-what-can-we-do-about-it-96745.

[5] Marie Stopes International,2020. Stories from the frontline: in the shadow of the Covid-19 pandemic, https://www.mariestopes.org/covid-19/stories-from-the-frontline.

[6] International Planned Parenthood Federation, 2020. Covid-19 pandemic cuts access to sexual and reproductive healthcare for women around the world, 2020, https://www.ippf.org/news/covid-19-pandemic-cuts-access-sexual-and-reproductive-healthcare-women-around-world.

[7] Falcone R E, Detty A. 2015. “The Next Pandemic: Hospital Response.” Emergency Medical Reports 36 (26): 1–16.

[8] International Federation of Gyanecology and Obsteric, 2020. Covid-19 Contraception and Family Planning: Contraceptive and Family Planning services and supplies are CORE components of essential health services, and access to these services is a fundamental human right.

[9] Guanjian Li, Dongdong Tang et al., 2020: Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Partner Relationships and Sexual and Reproductive Health: Cross-Sectional, Online Survey Study, Published on 6.8.2020 in Vol 22, No 8 (2020).

[10] Kavita Nanda, et al, 2020. Contraception in the Era of Covid-19, Glob Health Sci Pract. 2020 Jun 30; 8(2): 166–168. Published online 2020 Jun 30. Doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-20-00119 PMCID: PMC7326510, PMID: 32312738.

[11] Weinberger M, Hayes B, et al., 2020: Doing things differently: what it would take to ensure continued access to contraception during Covid-19. Glob Health Sci Pract, 8, pp. 169-175.

[12] Modupe Taiwo, et al, 2020. Gendered Impact of Covid-19 on the Decision-Making Power of Adolescents in Northern Nigeria, Save the Children Nigeria.

[13] Kantorová V, et al.,2020 Estimating progress towards meeting women’s contraceptive needs in 185 countries: A Bayesian hierarchical modelling study. PloS Med 17(2): e1003026. https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/articleid=10.1371/journal.pmed.1003026.

[14] United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2019. Family Planning and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations.

[15] WHO, 2007. Maternal mortality in 2005; Estimates Developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and The World Bank, WHO, Geneva 2007.

[16] Lule E, et al., 2007. Fertility regulation behavior and their costs: contraception and unintended pregnancies in Africa and Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Washington: World Bank; 2007.

[17] Kayode Afolabi, 2020. Sustaining FP & Sexual Reproductive Reproductive Health Services Delivery amidst Covid-19 Pandemic, Director/Head RH Division, Federal Ministry of Health.

[18] Aishat Bukola Usman, Olubunmi Ayinde, et al, 2020. Epidemiology of Corona Virus Disease 2019 (Covid-19) Outbreak Cases in Oyo State, Southwest Nigeria March -April 2020. DOI:10.21203/rs.3.rs-29502/v1.

[19] National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF. 2019. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA A: NPC and ICF.

[20] Ezugwu EC, Nkwo PO, Agu PU, Ugwu EO, Asogwa AO, 2014. Contraceptive use among HIV-positive women in Enugu, southeast Nigeria. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2014; 126:14-7.

[21] USAID, 2020. Monitoring Covid-19’s Effects on Family Planning: What Should We Measure?

[22] FP2020, Measurement, no date, http://progress.familyplanning2020.org/measurement.

[23] Michelle Weinberger et al, 2020: Doing Things Differently: What It Would Take to Ensure Continued Access to Contraception During Covid-19. Global Health: Science and Practice, 8(2):169-175; https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-20-00171.

[24] Sorpreso ICE, et al, 2015. Sexually vulnerable women: could long-lasting reversible contraception be the solution? Rev Bras Ginecol E Obstet.; 37:395–396.

[25] Taylor Riley et al., 2020. Estimates of the Potential Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Sexual and Reproductive Health in Low- and Middle-Income Countries, International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, A journal of peer-reviewed research, volume 46, page 73-76.

Viewed PDF 1134 25 -

Results of Unintentional Injuries among Preschool Children Enrolled in Day-care Centers from Selected Villages around Gaborone, BotswanaAuthor: Kedibonye Tsaone Mmachere MarekaDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art007

Results of Unintentional Injuries among Preschool Children Enrolled in Day-care Centers from Selected Villages around Gaborone, BotswanaAuthor: Kedibonye Tsaone Mmachere MarekaDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art007Results of Unintentional Injuries among Preschool Children Enrolled in Day-care Centers from Selected Villages around Gaborone, Botswana

Abstract:

This study employed a descriptive cross-sectional study qualitative and quantitative designs to gather data through structured interviews, questionnaires over a certain period in time in the past (retrospective) and the present (concurrent), and then analyze the results. The study was undertaken in the selected villages around Gaborone Botswana, situated in the south of the country. Its final focus was to publish the research results from a research survey done on unintentional injuries among preschool children enrolled in day-care centers from selected villages around Gaborone, Botswana. The population consisted of 47-day care centers in the selected villages around Gaborone which are all situated in Mogoditshane/Thamaga Subdistrict. A sample of 45 care centers was drawn using Yamane formula. Data were then collected through auditing, structured interviews, and questionnaires. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) program was used to analyze the data. The summary of the results of the current study show that: i) Males are more likely to get injured than females ii) Older children are more likely to sustain UI (iii) UI are sustained in the late afternoons iv) UI are more likely to be sustained in the early and late part of the week v) Season or term of study is not a factor of UI vi) Amount of time spent at school is a factor of UI (Davis, Godfrey & Rankin 2013).The findings indicate that there are factors that can have a negative influence on the occurrence of unintentional injuries in day care centers. It is suggested that a supportive teaching programme in the form of a workshop for service providers, teachers and parents should be designed, that will support the system of unintentional injury prevention program for preschool children in day care centers in order to prevent unintentional injuries in the selected villages around Gaborone, Botswana.

Keywords: Contributing factors to unintentional injuries, Day care centers / pre-schools/ preprimary units, Interventions on unintentional injury prevention, Unintentional injuries, Unintentional injuries prevention, the Prevalence of unintentional injuries in childcare settings.Results of Unintentional Injuries among Preschool Children Enrolled in Day-care Centers from Selected Villages around Gaborone, Botswana

References:

[1] Daycare centers and pre-schools under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) http://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fact-sheet/46-flsa-daycare(2009).

[2] Hoffnung, M., Hoffnung, R. J., Seifert, K. L., Burton Smith, R., & Hine, A. (2010). Childhood (1st ed.). Milton, Old: John Wiley & Sons Australia.

[3] Phelan KJ,Khoury J, Kalkwarf HJ,Lanphear BP.Trends and patterns of playground injuries in United States children and adolescents (20010. Ambulatory Pediatrics 2001; 1(4):227-33. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F003335490512000111.

[4] Macarthur Colin, Hu Xiaohan, Wesson David E &Parkin Patricia C. (2000). Risk factors for severe injuries associated with falls from playground equipment. Analysis and prevention, 32(3):377-82. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(99)00079-2.

[5] Gong1 Hairong, Guoping Lu, Jian Ma1, Jicui Zheng, Fei Hu1, Jing Liu1, Jun Song, Shenjie Hu1, Libo Sun1, Yang Chen1, Li Xie, Xiaobo Zhang, Leilei Duan6 and Hong Xu (2021) Causes and Characteristics of Children Unintentional Injuries in Emergency Department and Its Implications for Prevention Public Health PMC8374066. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.669125.

[6] CDC (2013). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury, Violence, and Safety. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/InjuryViolenceSafety/.

[7] Unitentional injuries. Rhode Island department https://health.ri.gov/injury/ (n.d.).

[8] Mónica, R.-C. (2009). Unintentional Childhood injuries in Sub- Saharan Africa: An overview of risk and protective factors. Journal of Health care for the poor and undeserved, 20(4 Suppl):51-67 DOI:10.1353/hpu.0.0226.

[9] Yamane, Taro (1973) Statistics’, an introductory analysis, 2nd edition, New York: Harper International Edition jointly published by. Harper & Row.

[10] Davis Christopher S 1, Godfrey Sarah E, Rankin Kristin M (2013) Unintentional injury in early childhood: its relationship with childcare setting and provider. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 17(9):1541-9. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1110-z.

[11] Hashikawa A, Newton M.F, Stevens M, Cunningham R. M (2013) Unintentional injuries in childcare centers in the United States: A systematic review Journal of Child Health Care 19(1). DOI: 10.1177/1367493513501020.

[12] Chang A, Lugg M, Nebedum M, (1989) Injuries among pre-school children enrolled in daycare centers. Pediatrics (1989) 83 (2): 272–277. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.83.2.272.

[13] Sacks Smith JD,Kaplan KM, Lambert DA,Sattin RW, Sikes( 1989) RK The epidemiology of J injuries in Atlanta daycare centers. JAMA, 01262(12):1641-1645 DOI: 10.1001/jama.1989.03430120095028 PMID: 2769919.

[14] Alkon A, Genevro JL, Kaiser PJ, Schann PJT, Chesney JM, Boyce M (1994) Injuries in childcare centers: Rates, severity, and etiology. Pediatrics 94(6 Pt 2):1043-6.

[15] Lee, E.J., & Bass, C. (1990). Survey of accidents in a university daycare center. Journal of Pediatric Health Care 4(1):18-23. doi: 10.1016/0891-5245(90)90035-5.

[16] Macarthur Colin, Hu Xiaohan, Wesson David E &Parkin Patricia C. (2000). Risk factors for severe injuries associated with falls from playground equipment. Analysis and prevention, 32(3):377-82. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(99)00079-2.

[17] Alkon A, Genevro JL, Tschann JM, et al. (1999) The epidemiology of injuries in 4 childcare centers. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 153(12):1248-54. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.12.1248.

[18] Hyder Adnan, Peden Margaret, Krug Etienne ( 2009) Child injuries and violence: The new challenge for child health Bulletin of the World Health Organisation 86(6):420 DOI:10.2471/BLT.08.054767.

[19] Davis, C.S., Godfrey, S.E., & Rankin, K.M. (2012). Unintentional injury in early childhood: Its relationship with childcare setting and provider. Maternal Child Health Journal, NLM Unique ID: 9715672. 17(9):1541-9. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1110-z.

[20] Petridou Eleni Th, Sibert J, Dedoukou J Xi, Skalkidis I. (2002). Injuries in public and private playgrounds: The relative contribution of structural,equipment and human factors. Acta Paediatrics, 2002; 91(6):691-7. doi: 10.1080/080352502760069133.

[21] Teck Hoc Toh,Lee Wong. (2006). Playground injuries in Singaporean children with special reference to falls from monkey-bars. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287080444.

[22] Lee, E.J., & Bass, C. (1990). Survey of accidents in a university daycare center. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 4(1):18-23 doi: 10.1016/0891- 5245(90)90035-5.

[23] Maundeni, T. (2013), Early Childhood Care and Education in Botswana: A Necessity That Is Accessible to Few Children. Creative Education, 04(07):54-59 DOI:10.4236/ce.2013.47A1008 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ce.

Viewed PDF 897 32 -

Knowledge, Attitude and Practice toward Nutrition among Communities in Southern Senatorial Zone of Borno StateAuthor: Ibrahim Musa NgosheDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art008

Knowledge, Attitude and Practice toward Nutrition among Communities in Southern Senatorial Zone of Borno StateAuthor: Ibrahim Musa NgosheDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art008Knowledge, Attitude and Practice toward Nutrition among Communities in Southern Senatorial Zone of Borno State

Abstract:

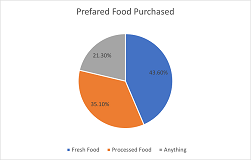

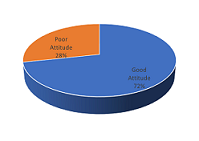

Nutrition is a key element of health promotion, prevention, and management of diseases. The study was aimed at assessing the nutritional knowledge, attitude, and practice of communities and to determine factors influencing the nutritional knowledge, attitudes, and practices of these communities. A cross-sectional study was conducted among 10 communities. Multistage sampling was used to select the sample size of 1000 individuals. The study utilized both primary and secondary data through journals and administration of a self-developed structured interviewer questionnaire and focus group discussions. The data was analyzed using statistical package for social science (SPSS v20). Results were presented using descriptive statistics and Chi-square. The findings of the study revealed that communities have little or no knowledge about nutrition despite the availability of different sources of nutritional information, majority of communities have a negative attitude towards the importance of nutrition because of their Cultural beliefs. Moreso, majority communities do not prepare balanced family meals. The result from chi-square analysis shows that age and source of nutritional knowledge are the main factors influencing nutritional knowledge and education level, marital status, and sources of family income are the main factors influencing nutritional practices among communities. Base on the findings of the study it was recommended among others that there is need to increased public awareness and enlightenment to improve the attitude and practice of communities, community leaders and health workers to promote good dietary habits and consumption of good indigenous food to motivate practice among communities.

Keywords: Attitude, Communities, Knowledge, Nutrition, Practice.Knowledge, Attitude and Practice toward Nutrition among Communities in Southern Senatorial Zone of Borno State

References:

[1] World Health Organization (2019) World Health Statistics: monitoring health for sustainable development goals: ISBN 978-92-4-156570-7.

[2] Givens D.I (2018) Dairy foods, red meat and processed meat in the diet: implications for health at key life stages. Animal12, 1709– 1721. Cambridge University Press.

[3] Triches, R. & Giugliani, E. (2005). Obesity, eating habits and nutritional knowledge among school children. Revista de Saúde Pública. 39:541-547.

[4] Ihab, A., Jalil, R., Manan, W., Wan N., Wan S., Mohd S., Zalilah & Abdullah, M. (2013). Nutritional Outcomes Related to Household Food Insecurity among Mothers in Rural Malaysia. Journal of health, population, and nutrition. 31: 480-9.

[5] Mirmiran, P., Azadbakht, L., & Azizi F. (2007) Dietary behaviour of Tehranian adolescents does not accord with their nutritional knowledge. Journal Public Health Nutrition 10(9):897-901.

[6] Kigaru, D.M.D., Loechl, C., Moleah, T. (2015) Nutrition knowledge, attitude and practices among urban primary school children in Nairobi City, Kenya: a KAP study. BMC Nutrition 1(44). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-015-0040-8.

[7] Kalu, R.E and Etim, K.E (2018) Factors Associated with Malnutrition among Underfive Children in Developing Countries: A Review. Global journal of pure and applied sciences 24: 69-74 ISSN 1118-0579 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/gjpas.v24i1.8.

[8] Berti C, Cetin I, and Agostoni C. (2016) Pregnancy and infants’ outcome: nutritional and metabolic implications. Crit Rev Food Science Nutrition. 56:82-91.

[9] Uddin M.T., Islam M.N. & Uddin MJ (2008) A survey on knowledge of nutrition of physicians in Bangladesh: evidence from Sylhet data. South East Asian Journal Medical Education. 2:14–17.

[10] Vahyala A.T., Minnessi G.K. and Kabiru U. (2016). The effects of Boko Haram insurgency on food security status of some selected local government areas in Adamawa State, Nigeria. Sky Journal of Food Science 5(3): 012 – 018.

[11] Nahikian-Nelms, M. (1997) Influential Factors of Caregiver Behavior at Mealtime: A Study of 24 Child Care Programs. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, (97), 505-509.

[12] Bakhtiar M.D., Masud-ur-Rahman M.D., Kamruzzaman Nargis Sultana M.D and Shaikh S.S. (2021) Determinants of nutrition knowledge, attitude and practices of adolescent sports trainee: A cross-sectional study in Bangladesh. Heliyon Journal 7(1):1-11.

[13] Jeinie, M.H.B.; Guad, R.M.; Hetherington, M.M.; Gan, S.H.; Aung, Y.N.; Seng,W.Y.; Lin, C.L.S.; George, R.; Sawatan,W.; Nor, N.M. (2021) Comparison of Nutritional Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices between Urban and Rural Secondary School Students: A Cross-Sectional Study in Sabah, East Malaysia. Foods. 10, 2037. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10092037.

[14] Fasola O, Abosede O, Fasola F.A. (2018). Knowledge, attitude and practice of good nutrition among women of childbearing age in Somolu Local Government, Lagos State. Journal Public Health African. 9(1):793.

[15] Charles S.R., Ismail S., Ahmad N., Ying L.P, Abubakar N.I. (2016) Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Adolescent Girls towards Reducing Malnutrition in Maiduguri Metropolitan Council, Borno State, Nigeria: Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients. ;12(6):1681.

[16] Likert, R. (1932). A technique for measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 140, 5-55.

[17] Kassahun, C.W., Mekonen, A.G. (2017) Knowledge, attitude, practices and their associated factors towards diabetes mellitus among non-diabetes community members of Bale Zone administrative towns, South East. Journal of Medical Science 12(1):34-37.

[18] Uba, M. N., Alih, F. I., Kever, R.T. & Lola, N. (2015). Knowledge, attitude and practice of nurses toward pressure ulcer prevention in University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital, Borno State, North-Eastern, Nigeria. International Journal of Nursing and Midwifery, 7(4), 54-60.

[19] Kaur, K., Grover, K., & Kaur, N. (2016). Assessment of Nutrition Knowledge of Rural Mothers and Its Effectiveness in Improving Nutritional Status of Their Children. Indian Research Journal of Extension Education, 15, 90-98.

[20] Farjana R.B, Joti Lal B., Kazi Abul K. (2021) Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Regarding Nutrition among Adolescent Girls in Dhaka City: A Cross-sectional Study. Nutrition Food Science International Journal. 10(4): 555795. DOI: 10.19080/NFSIJ.2021.10.555795.

[21] Sulaiman S., Muhammad G.A, Muhammad A.S., Abubakar H., and Abubakar S.M. (2020). Assessment of nutritional status, knowledge, attitude, and practices of infant and young child feeding in Kumbotso local government area, Kano State, Nigeria. Pakistan Journal Nutrition 19: 444-450.

[22] French, S. A., Wall, M., & Mitchell, N. R. (2010). Household income differences in food sources and food items purchased. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity, 7, 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-7-77.a.

Viewed PDF 1510 131 -

Estimating the Biological Age and the Magnitude of Lifestyle Determinants of Ageing among Nigerian AdultsAuthor: Abiodun Bamidele AdelowoDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art009

Estimating the Biological Age and the Magnitude of Lifestyle Determinants of Ageing among Nigerian AdultsAuthor: Abiodun Bamidele AdelowoDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art009Estimating the Biological Age and the Magnitude of Lifestyle Determinants of Ageing among Nigerian Adults

Abstract:

Considering the various limitations of using chronological age, biological age estimation is becoming increasingly recognized as one of the novel public health and clinical strategies for preventing and controlling the rising global prevalence of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and for achieving healthy ageing. The objectives of this study are to estimate the biological age and compare it to the chronological age of Nigerian adults. Also, to score the magnitude of some of the lifestyle determinants of biological age among the study population. This cross-sectional study uses simple random sampling technique to select 82 Nigerian adults for the study, while standardized instruments were used to collect data. The P value for the study was set at 0.05 level of significance. The result of the study noticed poor mean Mediterranean Diet Adherence (MDAQ) score of 7.0 ± 2.28 and mean International Physical Activity (IPAQ) score of 1.3 ± 0.51. There was also suboptimal mean Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) score of 5.9 ± 3.01, mean Perceive Stress Scale-4 (PSS-4) score of 6.3 ± 2.79, and mean Social Connectedness Scale (SCS) score of 15.2 ± 4.13. Furthermore, the estimated biological age of the respondents (45.9 years, ±10.31), was higher than their chronological age (43.2 years, ±8.92). The study concluded that the magnitudes of the lifestyle determinants of ageing are high enough to result in accelerated biological ageing among the study population. Such development, if not mitigated, may result in a significant increase in the prevalence of NCDs and premature deaths in the near future.

Keywords: Accelerated Ageing, Biological Age, Chronological Age, Lifestyle determinants of ageing, Health Promotion Intervention.Estimating the Biological Age and the Magnitude of Lifestyle Determinants of Ageing among Nigerian Adults

References:

[1] Pathath A.W., 2017, Theories of Aging. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 4 (3), 15 – 22. https://DOI:10.25215/0403.142.

[2] Jia L., Zhang W., and Chen X., 2017, Common methods of biological age estimation. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 12, 759–772.

[3] Cavallasca J., 2017, Measuring aging: what is your physiological age? Date of access: 2/4/2021. http://www.longlonglife.org/en/transhumanism-longevity/aging/measure-of-aging/measuring-aging-physiological-age/.

[4] Jiang S., and Guo Y., 2020, Epigenetic Clock: DNA Methylation in Aging. Stem Cells International, 2020, 1 – 9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/1047896.

[5] Kim S., and Jazwinski S.M., 2015, Quantitative measures of healthy aging and biological age. Healthy Aging Res., 4, 1 – 25. http://doi:10.12715/har.2015.4.26.

[6] Rollandi G.A., Chiesa A., Sacchi N., Castagnetta M., Puntoni M., Amaro A., et al., 2019, Biological Age versus Chronological Age in the Prevention of Age Associated Diseases, OBM Geriatrics, 3(2), 1 – 14, https://doi:10.21926/obm.geriatr.1902051.

[7] Kim S., Myers L., Wyckoff J., Cherry K.E., and Jazwinski S.M., 2017, The frailty index outperforms DNA methylation age and its derivatives as an indicator of biological age. GeroScience, 39, 83 – 92. https://DOI10.1007/s11357-017-9960-3.

[8] Waters D., 2020, This biological age calculator shows how old your body is. Date of access: 4/6/2021. https://www.womanandhome.com/health-and-wellbeing/biological-age-calculator-20430/.

[9] Kresovich J.K., Xu Z., O’Brien K.M., Weinberg C.R., Sandler D.P., and Taylor J.A., 2019, Methylation-Based Biological Age and Breast Cancer Risk. J Natl Cancer Inst., 1, 111(10), 1051-58. https://doi:10.1093/jnci/djz020.

[10] Waters D., 2020, This biological age calculator shows how old your body is. Date of access: 4/6/2021. https://www.womanandhome.com/health-and-wellbeing/biological-age-calculator-20430/.

[11] Federal Ministry of Health of Nigeria, 2015, National Strategic Plan of Action on Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases. Date of access: 21/7/2021 https://www.medbox.org/document/nigeria-national-strategic-plan-of-action-on-prevention-and-control-of-non-communicable-diseases#GO.

[12] World Health Organization, 2018, Non-communicable Diseases Country profiles 2018. Date of access: 21/7/2022. https://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd-profiles-2018/en/.

[13] Thompson A.E., Anisimowicz Y., Miedema B., Hogg W., Wodchis W.P., & Aubrey-Bassler K., 2016, The influence of gender and other patient characteristics on health care-seeking behaviour: a QUALICOPC study, BMC Family Practice, 17, 38. https://DOI:10.1186/s12875-016-0440-0.

[14] Lim M.T., Lim Y.M.F., Tong S.F., and Sivasampu S., 2019, Age, sex and primary care setting differences in patients’ perception of community healthcare seeking behaviour towards health services, PLoS ONE 14(10), e0224260. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224260.

[15] de Wit J.B.F., Peeters M., and Koning I., 2022, Risk Behaviour and Health Outcomes of Adolescents and Young Adults. Date of access: 20/7/2022. https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/5907/risk-behaviour-and-health-outcomes-of-adolescents-and-young-adults.

[16] Hilz R., & Wagner M., 2018, Marital Status, Partnership and Health Behaviour: Findings from the German Ageing Survey (DEAS). Comparative Population Studies, 43, 65-98. https://DOI:10.12765/CPoS-2018-08en.

[17] Fuchs M., 2021, Want to add healthy years to your life? Here’s what new longevity research says. Date of access: 9/8/2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/wellness/longevity-research-diet-exercise-tips/2021/10/10/edb5cdc2-2856-11ec-9de8-156fed3e81bf_story.html

[18] Abuduxike G., Aşut Ö, Vaizoğlu S.A., and Cali S., 2020, Health-Seeking Behaviors and its Determinants: A Facility-Based Cross-Sectional Study in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. Int J Health Policy Manag, x(x), 1–10. https://Doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2019.106.

[19] International Diabetes Federation, 2021, IDF Diabetes Atlas 10th edition. Date of access: 20/7/2022. https://diabetesatlas.org/idfawp/resource-files/2021/07/IDF_Atlas_10th_Edition_2021.pdf.

[20] Federal Ministry of Health of Nigeria, 2021, National Guideline on The Prevention, Control and Management of Diabetes Mellitus. Date of access: 21/7/2022. https://www.health.gov.ng/doc/National%20Guideline%20for%20the%20prevention,%20control%20and%20management%20of%20Diabetes%20Mellitus%20in%20Nigeria%20(3).pdf.

[21] World Health Organization, 2011, Global Status Report on Non-Communicable Diseases 2010. Date of access: 21/7/2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44579/9789240686458_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[22] Furman D., Campisi J., Verdin E., Carrera-Bastos P., Targ S., Franceschi C., et al., 2019, Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nature Medicine, 25, 1822 – 1832. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0675-0.

[23] Akarolo-Anthony S.N., Willett W.C., Spiegelman D., and Adebamowo C.A. Obesity epidemic has emerged among Nigerians. BMC Public Health 2014, 14:455. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/455.

[24] Chukwuonye I.I., Chuku A., John C., Ohagwu K.A., Imoh M.E., Isa S.E., et al., 2013, Prevalence of overweight and obesity in adult Nigerians – a systematic review. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy, 6, 43–47.

[25] Södergren M., 2013, Lifestyle predictors of healthy ageing in men. Maturitas., 75(2), 113-7. https://DOI:10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.02.011.

[26] Adelowo A.B., 2021, Analyzing the Magnitude of Global Epidemiological Transition in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Need to Review the Current Healthcare Management Approach. Texila International Journal of Public Health, 9 (3); 204 – 212. https://DOI:10.21522/TIJPH.2013.09.03.Art018.

[27] Adelowo A.B., 2022, A Scoping Review of Cardio-Metabolic Syndrome: A Critical Step in Mitigating the Rising Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Diabetes Mellitus. Int J Diabetes Metab Disord, 7(1): 80-86. https://doi.org/10.33140/IJDMD.07.01.13.

[28] Federal Ministry of Health of Nigeria, 2014, National Nutritional Guideline on Non-Communicable Disease Prevention, Control and Management. Date of access: 13/12/2016. http://www.health.gov.ng/doc/NutritionalGuideline.pdf.

[29] Agu AU, Esom EA, Chime SC, Anyaeji PS, Anyanwu GE, and Obikili EN., 2021, Impact of sleep patterns on the academic performance of medical students of College of Medicine, University of Nigeria. Int J Med Health Dev, 26, 31-6.

[30] Onoh I., 2017, World Sleep Day: How sleep deprivation threatens Lagosians’ wellbeing – Expert. Date of access: 4/8/2022. https://www.environewsnigeria.com/world-sleep-day-sleep-deprivation-threatens-lagosians-wellbeing-expert/.

[31] Adelowo A.B, 2020, Sleep: An Insight into the Neglected Component of a Healthy Lifestyle. Nigerian School of Health Journal, 32 (1), 75-87.

[32] Wilson D., Driller M., Johnston B., and Gill N., 2021, The effectiveness of a 17-week lifestyle intervention on health behaviors among airline pilots during COVID-19. J Sport Health Sci, 10, 333 – 40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2020.11.007.

[33] Iyizoba N., 2017, Nigeria: Managing Stress in World’s Most Stressful Country. AllAfrica, 2017. Date of access: 5/8/20222. https://allafrica.com/stories/201709140833.html.

[34] ThisDay, 2021, Nigeria: The Stress of Living in Lagos. AllAfrica, 2021. Date of access: 5/8/2022. https://allafrica.com/stories/202106280283.html.

[35] Onigbogi C.B., and Banerjee S., 2019, Prevalence of Psychosocial Stress and Its Risk Factors among Health-care Workers in Nigeria: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Niger Med J.60(5), 238–244. https://doi:0.4103/nmj.NMJ_67_19.

[36] Ogbujah C, 2014, African Cultural Values and Inter-communal Relations: The Case with Nigeria. Developing Country Studies 2014: 4 (24): 208-17.

[37] Onuoha F., 2015, Onuoha Frank: Locating African Values in Twenty–First Century Economics. ASFL, 2018. Date of access: 5/8/2022. https://www.africanliberty.org/2015/09/09/onuoha-frank-locating-african-values-in-twenty-first-century-economics/.

[38] Sibani C.M., 2018, Impact of Western Culture on Traditional African Society: Problems and Prospects. International Journal of Religion and Human Relations 2018; 10 (1): 56 – 72.

[39] Watson K.,2019, Everything You Need to Know About Premature Ageing. Date of access: 24/11/2020. https://www.healthline.com/health/beauty-skin-care/premature-aging#tips-for-prevention.

[40] Sandoiu A., 2017, Sedentary lifestyle speeds up biological aging, study finds. Date of access: 21/6/2021. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/315347#Sedentary-women-biologically-older-by-8-years.

[41] Irwin M.R.,2014, Sleep and inflammation in resilient aging. Interface Focus, 4 (20140009), 1 – 7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2014.0009.

[42] He M., Deng X., Zhu Y., Huan L., and Niu W., 2020, The relationship between sleep duration and all-cause mortality in the older people: an updated and dose-response meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 20 (1179), 1 – 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09275-3.

[43] Korab A., 2021, Everyday Habits That Age You Faster, According to Science: Look younger and be healthier with this essential advice. Date of access: 21/2/2021. https://www.eatthis.com/news-health-habits-age-science/.

[44] Franklin B.A, and Cushman M., 2011, Recent Advances in Preventive Cardiology and Lifestyle Medicine. Circulation, 123, 2274 – 2283.

[45] Miller J., 2011, The Fountain of Youth: The Quest for Biological Immortality. Date of access: 8/5/2021. http://www.slideshare.net/Justin2226/human-longevity-by-justin-miller.

[46] Whitbourne S.K., 2012, What’s Your True Age? You may be a lot younger than you think. Date of access: 8/4/2021. https://www.commonlit.org/texts/what-s-your-true-age.

Viewed PDF 1103 19 -

Assessment of Utilization of Standing Order in the Management of Patients by Community Health Extension Workers in Ekiti State, NigeriaAuthor: Rasheed Adeyemi AdepojuDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art010

Assessment of Utilization of Standing Order in the Management of Patients by Community Health Extension Workers in Ekiti State, NigeriaAuthor: Rasheed Adeyemi AdepojuDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art010Assessment of Utilization of Standing Order in the Management of Patients by Community Health Extension Workers in Ekiti State, Nigeria

Abstract:

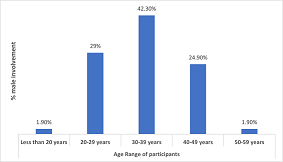

Engagement and training of community health extension workers was the strategy adopted by Nigeria to solve the problem of the dearth of skilled health workers at the primary health care level. This group of health workers were trained to use standing orders in the management of the patient at this level of care. The purpose of this study is to investigate the extent of utilization of standing order among community health extension workers. The research was cross-sectional in nature, and it used a self-applied structured questionnaire. The questionnaire was distributed between March and April 2022. There were 265 respondents with age ranges between 23 and 58 years, and the majority (86.7%) were females. 98.1% possessed a copy of the standing order, and 88.5% and 9.9% kept their standing orders in health facilities and home, respectively. 62.3% used it regularly, 19.6% occasionally, 8.3% sometimes and 9.8% rarely used it. Reasons given for not using standing orders included- waste of time, patients who think I am not competent, and not containing new drugs. Regular utilization of standing order is low, and there is a need to educate the community extension workers on the importance of standing order at the primary health care level.

Keywords: Standing order, Standardization, Utilization.Assessment of Utilization of Standing Order in the Management of Patients by Community Health Extension Workers in Ekiti State, Nigeria

References:

[1] Ibrahim D.O: Assessment of the Use of National Standing Orders in the Treatment of Minor Ailments among Community Health Practitioners in Ibadan Municipality. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 2016; 6(10): 50-54.

[2] James Macinko, Barbara Starfield and Temitope Erinosho: The Impact of Primary Healthcare on Population Health in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. J Ambulatory Care Manage, 2009; 32(2): 150-171.

[3] Taiwo Akinyede Obembe, Kayode Omoniyi Osungbade, and Christianah Ibrahim: Appraisal of primary health care services in federal capital territory, Abuja, Nigeria: How committed are health workers. The Pan African Medical Journal, 2017; 28: 134.

[4] Bolaji Shamson Aregbeshola and Samina Mohsin Khan: Primary Health Care in Nigeria: 24 years after Olikoye-Ransome Kuti’s Leadership. Frontiers in Public Health, 2017; 5:48/.

[5] Alenoghena I., Aigbiremolen A.O., Abejegha C. and Eboreime E: Primary health care in Nigeria: Strategies and constraints in implementations. International Journal of Community Research, 2014; 3(3): 74-79.

[6] Abdulraheem I.S., Olapipo A.R. and Amodu M.O: Primary health care services in Nigeria: Critical issues and strategies for enhancing the use by the rural communities. Journal of Public Health and Epidemiology, 2012; 4(1): 5-13.

[7] Gideon E.D.O: Perspective on Primary Health Care in Nigeria: Past, Present, and Future. Centre for Population and Environmental Development, 2014; Series No 10.

[8] Seye Abimbola, Titilayo Olanipekun, Uchenna Igbokwe, Joel Negin, Stephen Jan, Alexandra Martiniuk, Nnenna Ihebuzor, and Muyi Aina: How decentralization influences retention of primary health workers in rural Nigeria. Global Health Action, 2015; 8:26616.

[9] Seye Abimbola, Titilope Olanipekun, Marta Schaaf, Joel Negin, Stephen Jan and Alexandra L.C. Martinuik: Where there is no policy: governing the posting and transfer of primary health care workers in Nigeria. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 2017; 32: 492-508.

[10] Olayinka Akanke Abosede and Olugbenga Fola Sholeye: Strengthening the Foundation for Sustainable Primary Health Care Services in Nigeria. Primary Health Care, 2014; 4(3).

[11] Primary health care systems (PRIMASYS): case study from Nigeria. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Licence: CCBY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

[12] Tamara Kredo, Susanne Bernhardsson, Taryn Young, Quinette Louw, Eleanor Ochodo and Karen Grimmer: Guide to clinical practice guidelines: the current state of play. International Journal of Quality in Health Care, 2016; 28(1): 122-128.

[13] Irving R. Tabershaw and Margaret S. Hargreaves: Functions of Standing Orders for the Nurses in Industry. American Journal of Public Health, 1947; 37: 1430- 1434.

[14] Guerrero GP, Beccaria LM, and Trevizan MA: Standard operating procedure: Use in nursing care in hospital services. Rev Latino-am Enfermagem, 2008; 16(6): 966-972

[15] Walter RR, Gehlen MH, Ilha S, Zamberlan C, Barbosa de Freitas HM, and Pereira FW: Standard operation procedure in the nursing context: the nurses’ perception. Rev Fund Care Online. 2016 out/dez; 8(4): 5095-5100. DOI: http.dx.doi, org:10.9789/21755361. 2016.v8i4.5095-5100.

[16] Fatima Riskat Rahji: Knowledge, Perception and Utilization of integrated Management of Childhool Illnesses among Health care Workers in selected Primary Health Care Facilities in Ibadan, Nigeria. Nursing and Midwifery Council of Nigeria, 2018.

[17] Oyewole MF: Utilization of Primary Health Care Services Among Rural Dwellers in Oyo State. Nigeria Journal of Rural Sociology, 2018; 18(1): 106-111.

[18] Seye Abimbola, Titilope Olanipekun, Marta Schaaf, Joel Negin, Stephen Jan, and Alexandra L.C. Martinuik: Where there is no policy: governing the posting and transfer of primary health care workers in Nigeria. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 2017; 32: 492-508.

[19] V Lukali and C Michelo: Factors associated with Irrational Drug use at a District Hospital in Zambia: Patient Record-Based Observation. Medical Journal of Zambia, 2015; 42(1): 25-30.

[20] Mekonnen Sisay, Getnet Mengistu, Bereket Molla, Firehiwot Amare, and Tesfaye Gabriel: Evaluation of rational drug use based on World Health Organization core drug use indicators in selected public hospitals in eastern Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Health Services Research, 2017; 17:161. DOI.10.1186/s12913-017-2097-3.

[21] Basheer A.Z. Chedi, Ibrahim Abudu-Aguye and Helen O. Kwanashie: Drug use pattern in out-patient children: a comparison between primary and secondary health care facilities in Northern Nigeria. African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 2015; 9(4): 74-81.

[22] Bosse G, Schmidbauer W, Spies CD, Sorensen M, Francis RCE, Bubser F, Krebs M and Kerner T: Adherence to Guidelines –based Standard Operating Procedures in Pre-hospital Emergency Patient with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases. The Journal of International Medical Research, 2011; 39: 267-276.

[23] Al-Mounawara Yaya: Reducing Under-five Childhood Mortality using IMCI/e-IMCI: Implementation Approaches in Nigeria. A Master’s Paper submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of master’s in public health in the Global Public Health Program at The Gillings School of Global Public Health, 2017.

[24] Grace Komuhangi, Nwana Uchechukwu Kevin, Ilori Oluwole Felex and Lydia Kabiri: Factors Associated with Compliance with Infection Control Guidelines in the Management of Labour by Healthcare Workers at Mulago Hospital, Uganda. Open Journal of Nursing, 2019; 9(7): 697- 723. doi: 10.4236/ojn.2019.97054

[25] Sarah Lodel, Christoph Ostgathe, Maria Heckel, Karin Oechsle and Susanne Gahr: Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) for Palliative Care in German Comprehensive Cancer Centres – an evaluation of implementation status. MBC Palliative Care, 2020; 19(62).

[26] Lamin E.S. Jaiteh, Stefan A Helwig, Abubacarr Jagne, Andreas Ragoschle-Schumm, Catherine Sarr, Silke Walter Martin Lesmeister, Dipl-Phys Matthias Manitz, Sebastian Blab, Sarah Weis, Verena Schlund, Neneh Bah, Jil Kauffmann, Mathias Fousse, Sabina Kangankan, Asmell Ramos Cabrera,

Kai Kronfeld, Christian Ruckes, Dipl-Math Yang Liu, Ousman Nyan, and Klaus Fassbender: Standard operating procedures improve acute neurologic care in a sub-Saharan African setting. Neurology, 2017; 89: 144-152. DOI 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004080.[27] Hongxia Zhang, Zonghong Zhu, Xiaoyan Wang, Xiaofeng Wang, Limin Fan, Ranran Wu, and Chenjing Sun: Application Effect of the Standard Operation Procedures in the Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism. Journal of Healthcare Engineering, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5019898.

[28] David M.O. Omoit, George O. Otieno and Kenneth K. Rucha: Measuring the Extent of Compliance to Standard Operating Procedures for Documentation of Medical Records by Healthcare Workers in Kenya. Public Health Research, 2020; 10(2): 78-86. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20201002.06.

Viewed PDF 1116 46 -

Vaccine Management Knowledge and Practice of Health workers in YemenAuthor: Victor SuleDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art011

Vaccine Management Knowledge and Practice of Health workers in YemenAuthor: Victor SuleDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.04.Art011Vaccine Management Knowledge and Practice of Health workers in Yemen

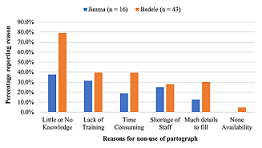

References: