Table of Contents - Issue

Recent articles

-

Disorders of Blood Gases, Electrolytes, Magnesium, Albumin and Calcium Metabolism in SARS-CoV-2-infected PatientsAuthor: Ajibola AdisaDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.01.Art001

Disorders of Blood Gases, Electrolytes, Magnesium, Albumin and Calcium Metabolism in SARS-CoV-2-infected PatientsAuthor: Ajibola AdisaDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.01.Art001Disorders of Blood Gases, Electrolytes, Magnesium, Albumin and Calcium Metabolism in SARS-CoV-2-infected Patients

Abstract:

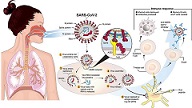

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2)-infection is characterized by several malfunctions, including severe pulmonary disorders. Other metabolic consequences of SARS-CoV-2-infection have not been clearly defined. The present study assessed the status of blood gases, calcium metabolism, and electrolytes in SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals. One hundred and thirty-four newly diagnosed SARS-CoV-2-infected patients (age ranged 65-82years) attending Mullingar Regional Hospital, Republic of Ireland, participated in this study. They all had pulmonary disorders, pyrexia, body pains, etc. SARS-CoV-2 was confirmed in all patients using the RT-PCR molecular test method. The data of another 121 plasma samples of apparently normal, non-SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals taken before the emergence of Covid-19 served as controls. Levels of partial pressure of oxygen (pO2), saturated oxygen (SatO2), partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2), and ionized calcium (Ca2+) were determined in all participants using the potentiometric method in RAPIDPOINT 500 Blood Gases System. Plasma vitamin-D was determined by immune enzymatically technique using DXi 800 Access Immunoassay System. Total calcium, phosphate, albumin, magnesium, and electrolytes were determined by the photometric method using Beckman Au680- Chemistry Analyzer. The results showed significantly (p<0.05) higher levels of pCO2 and HCO3- in COVID-19-patients compared to controls. Significantly(p<0.05) lower levels of pO2, SatO2, pH, K+, albumin, total-calcium, Ca2+, magnesium, and vitamin-D were observed in COVID-19 patients compared to controls. Corrected calcium, PO4-, Na+, and Cl- levels did not show significant (p>0.05) changes in the COVID-19-patients compared to controls. Abnormal blood gases, acidosis, hypomagnesaemia, hypoalbuminemia, hypovitaminosis D and calcium metabolic disorders could be features of COVID-19-disease.

Disorders of Blood Gases, Electrolytes, Magnesium, Albumin and Calcium Metabolism in SARS-CoV-2-infected Patients

References:

[1] Oudit GY, Kassiri Z, Jiang C, et al. 2009. Sars-Coronavirus modulation of myocardial ACE2 expression and inflammation in patients with SARS. Eur J Clin Invest. 39:618–25.

[2] Guo Y , Qing-Dong Cao, Zhong-Si Hong, Yuan-Yang Tan, Shou-Deng Chen, Hong-Jun Jin, Kai-Sen Tan, De-Yun Wang, Yan Yan 2020. The origin, transmission, and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) outbreak - an update on the status. Mil Med Res. 13;7(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-00240-0.

[3] Letko M, Marzi A, Munster V. 2020. Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B beta coronaviruses. Nat Microbiol. 5:562–9.

[4] Boermeester MA, van Leeuwen PAM, Coyle SM, et al., 1995. Interleukin-1 receptor blockade in patients with sepsis syndrome: evidence that interleukin-1 contributes to the release of interleukin-6, elastase phospholipase A2, and to the activation of the complement, coagulation, and fibrinolytic systems, Arch Surg, vol. 130; 739-48.

[5] Santos RA, Ferreira AJ, Simoes ESA. 2008. Recent advances in the angiotensin converting enzyme 2-angiotensin (1-7)-Mas axis. Exp Physiol. 93 (5):519–27.

[6] Zhang R, Wu Y, Zhao M, Liu C, Zhou L, Shen S, Liao S, Yang K, Li Q, Wan H. 2009. Role of HIF-1alpha in the regulation of ACE and ACE2 expression in hypoxic human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 297(4): L631–40.

[7] Aya Bassatne, Maya Basbous, Marlene Chakhtoura, Ola El Zein, Maya Rahme, Ghada El-Hajj Fuleihan 2021. The link between Covid-19 and VItamin D (VIVID): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism. 119:154753.

[8] Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. 2020. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 382: 1708–20.

[9] Klok FA, Kruip M, van der Meer NJM, et al. 2020. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with Covid-19. Thromb Res. Published online April 10. Doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013.

[10] Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, et al. 2020 Presenting Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Outcomes Among 5700 Patients Hospitalized with Covid-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6775 PMID: 32320003.

[11] Myers LC, Parodi SM, Escobar GJ, Liu VX 2020. Characteristics of Hospitalized Adults with Covid-19 in an Integrated Health Care System in California. JAMA.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.7202 PMID: 32329797.

[12] Assandri R, Buscarini E, Canetta C, Scartabellati A, Viganò G, Montanelli A., 2020. Laboratory Biomarkers Predicting Covid-19 Severity in the Emergency Room. Arch Med Res. 51 (6):598-599. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2020.05.011.

[13] Hinojosa-Velasco A, Bobadilla-Montes de Oca VP, García-Sosa LE, Mendoza-Durán JD, Pérez-Méndez MJ, Eduardo Dávila-González, Dolores G Ramírez-Hernández, Jaime García-Mena, Zárate-Segura P, Reyes-Ruiz JM, Bastida-González F., 2020 A Case Report of Newborn Infant with Severe Covid-19 in Mexico: Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Human Breast Milk and Stool. Int J Infect Dis. 26; S1201-9712(20)30684-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.08.055. Online ahead of print.

[14] Singhal T. 2020. A Review of Coronavirus Disease-2019 (Covid-19). Indian J Pediatr. 87(4):281-286. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03263-6. Epub 2020.

[15] Petrilli CM, Jones SA, Yang J, Rajagopalan H, O’Donnell L, Chernyak Y, et al. 2020. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 369: m1966. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1966 PMID: 32444366.

[16] Xie J, Covassin N, Fan Z, Singh P, Gao W, Li G, et al. 2020. Association Between Hypoxemia and Mortality in Patients with Covid-19. Mayo Clin Proc. 95: 1138–1147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp. 2020.04.006 PMID: 32376101.

[17] Mejı´a F, Medina C, Cornejo E, Morello E, Va´squez S, Alave J, et al. 2020. Oxygen saturation as a predictor of mortality in hospitalized adult patients with Covid-19 in a public hospital in Lima, Peru. PLoS One 15(12): e0244171. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244171.

[18] Eltzschig HK, Carmeliet P. 2011. Hypoxia and inflammation. N Engl J Med. 364: 656–665. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0910283 PMID: 21323543.

[19] Persechini A., Moncrief N.D., Kretsinger R.H 1989. The EF-hand family of calcium-modulated proteins. Trends Neurosci. 12: 462–467 [PubMed] [Google Scholar].

[20] Yang W., Lee H.W., Hellinga H., Yang J.J. 2002. Structural analysis, identification, and design of calcium-binding sites in proteins. Proteins. 47:344–356 [PubMed] [Google Scholar].

[21] Xingjuan Chen, Ruiyuan Cao, Wu Zhong 2019. Host Calcium Channels and Pumps in Viral Infections. Cells. Dec 30;9(1):94. doi: 10.3390/cells9010094.

[22] Zhou Y., Yang W., Kirberger M., Lee H.W., Ayalasomayajula G., Yang J.J. 2006. Prediction of EF-hand calcium-binding proteins and analysis of bacterial EF-hand proteins. Proteins. 65:643–655 [PubMed] [Google Scholar].

[23] Xi Zhou; Dong Chen Lan Wang; Yuanyuan Zhao; Lai Wei; Zhishui Chen; Bo Yang 2020. Low serum calcium: a new, important indicator of COVID-19 patients from mild/moderate to severe/critical. Biosci Rep. 40 (12): BSR20202690. https://doi.org/10.1042/BSR20202690.

[24] Hanley B, Lucas SB, Youd E, Swift B, Osborn M. 2020. Autopsy in suspected COVID-19 cases. Journal of Clinical Pathology 73:239–242.

[25] Miyazawa, M. 2020. Immunopathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2-induced pneumonia: lessons from influenza virus infection. Inflamm Regener 40, 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41232-020-00148-1.

[26] Wu Z, McGoogan JM. 2020. Characteristics of and Important Lessons from the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648 PMID: 32091533

[27] Andrew M Luks, Erik R Swenson 2020. Pulse Oximetry for Monitoring Patients with Covid-19 at Home. Potential Pitfalls and Practical Guidance. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 17(9):1040-1046 doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202005-418FR.

[28] Zhang R, et al. 2009. Role of HIF-1α in the regulation ACE and ACE2 expression in hypoxic human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 297: L631–L640 [PubMed] [Google Scholar].

[29] Jahani M, Dokaneheifard S, Mansouri K. 2020. Hypoxia: a key feature of Covid-19 launching activation of HIF-1 and cytokine storm. J. Inflamm. 17:33 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar].

[30] Ward PA, Fattahi F, Bosmann M. 2016. New insights into molecular mechanisms of immune complex-induced injury in the lung. Front. Immunol. 7:86 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar].

[31] Stenmark KR, Tuder RM, El Kasmi KC. 2015. Metabolic reprogramming and inflammation act in concert to control vascular remodeling in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. J. Appl. Physiol. 119:1164–1172 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar].

[32] Pugliese SC, et al. 2017. A time- and compartment-specific activation of lung macrophages in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. J. Immunol. 198:4802–4812 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar].

[33] Morne C Bezuidenhout, Owen J Wiese, Desiree Moodley, Elizna Maasdorp, Mogamat R Davids, Coenraad Fn Koegelenberg, Usha Lalla, Aye A Khine-Wamono, Annalise E Zemlin, Brian W Allwood. 2021. Correlating arterial blood gas, acid-base and blood pressure abnormalities with outcomes in Covid-19 intensive care patients. Ann Clin Biochem. 58(2):95-101. doi: 10.1177/0004563220972539 Epub 2020 Nov 20.

[34] Lippi, G, South, AM, Henry, BM. 2020. Electrolyte imbalances in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19). Ann Clin Biochem. 57:262-5.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0004563220922255 Search in Google Scholar

[35] Zhou Y, Teryl K. Frey, and Jenny J. Yang 2009. Viral calciomics: Interplays between Ca2+ and virus. Cell Calcium. 46(1): 1–17.

[36] Ruiz M.C., Cohen J., Michelangeli F 2000. Role of Ca2+ in the replication and pathogenesis of rotavirus and other viral infections. Cell Calcium. 28:137–149 [PubMed] [Google Scholar].

[37] Di Filippo, L, Formenti, AM, Rovere-Querini, P, Carlucci, M, Conte, C, Ciceri, F, et al. 2020. Hypocalcemia is highly prevalent and predicts hospitalization in patients with Covid-19. Endocrine. 68:475–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-020-02383-5 Search in Google Scholar.

[38] Antoniak S, Nigel Mackman., 2014. Multiple roles of the coagulation protease cascade during virus infection. Blood. 123 (17): 2605–2613. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-09-526277.

[39] Ryan MF 1991. The role of magnesium in clinical biochemistry: an overview. Ann Clin Biochem. 28:19–26 [PubMed] [Google Scholar].

[40] Swaminathan R 2003. Magnesium Metabolism and its Disorders. Clin Biochem Rev. 24(2): 47–66.

[41] Chuan-Feng Tang, Hong Ding, Rui-Qing Jiao, Xing-Xin Wu, and Ling-Dong Kong. 2020.. Possibility of magnesium supplementation for supportive treatment in patients with COVID-19. Eur J Pharmacol. 5; 886: 173546. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173546.

[42] Jacob S. Stevens, Andrew A. Moses, Thomas L. Nickolas, Syed Ali Husain, and Sumit Mohan. 2021, Increased Mortality Associated with Hypermagnesemia in Severe Covid-19 Illness. Kidney360. 2 (7) 1087-1094; Doi: https://doi.org/10.34067/KID.0002592021.

[43] Laure-Cranford AG, Krust MS, Riviere Y, Rey-Cuille MA, Montagnier L, Hovanessian AG. 1991. The cytopathic effect of HIV is associated with apoptosis. Virology. 185: 829-839.

[44] Rundk Hwaiz, Mohammed Merza, Badraldin Hamad, Shirin HamaSalih, Mustafa Mohammed, Harmand Hama 2021. Evaluation of hepatic enzymes activities in Covid-19 patients. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021; 97:107701. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp. 107701. Epub 2021 Apr 21.

[45] Yu, D., Du, Q., Yan, S. et al. 2021. Liver injury in Covid-19: clinical features and treatment management. Virol J 18, 121. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-021-01593-1.

[46] Xu Y, Yang H, Wang J, Li X, Xue C, Niu C, Liao P. 2021. Serum Albumin Levels are a Predictor of Covid-19 Patient Prognosis: Evidence from a Single Cohort in Chongqing, China. Int J Gen Med. 14:2785-2797 https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S312521.

[47] Juyi Li , Meng Li, Shasha Zheng, Menglan Li, Minghua Zhang, Minxian Sun, Xiang Li, Aiping Deng , Yi Cai & Hongmei Zhang. Plasma albumin

levels predict risk for non-survivors in critically ill patients with Covid-19. Biomarkers in medicine vol. 14. 10; 826-837.Viewed PDF 1071 55 -

Socio Demographic Profiles of Enuresis among Primary School ChildrenAuthor: Audu Hadiza MustaphaDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.01.Art002

Socio Demographic Profiles of Enuresis among Primary School ChildrenAuthor: Audu Hadiza MustaphaDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.01.Art002Socio Demographic Profiles of Enuresis among Primary School Children

Abstract:

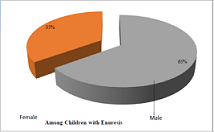

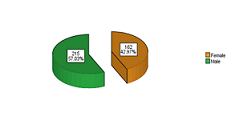

Enuresis is defined in many different ways, but the common thread to all involves a lack of bladder control after 5 years of age, an age when most children would be expected to have achieved bladder control. Nocturnal enuresis is best regarded as a condition with different etiologies. Many aetiological theories have been proposed, with the cause of nocturnal enuresis now regarded as heterogeneous. This was a cross-sectional, descriptive study of primary school children aged between 6-12 years. The study was conducted in Borno State in the northeastern part of Nigeria, West Africa. The sample size is 560, with 260(52.1%) males and 239 (47.9%) females. The ages of the respondents ranged from 6 to 12 years, with a mean age of 9.47 years and a Standard Deviation (SD) of ±1.85. Nine variables, namely age, gender, home environment, maternal education/occupation, paternal education/occupation, family size, and family history of enuresis among siblings at 95% CI were considered. The variables that have a significant relationship with enuresis when the chi 2 test was used were further subjected to logistic regression analysis. The children’s sex, age group, family history, fathers’ education, and occupation were found to have statistical significance in predicting bedwetting among children. Health educators and primary care health staff should obtain detailed history not to miss patients with enuresis, and parents should be informed about the psychological effects of Enuresis and to seek appropriate treatment for their children.

Socio Demographic Profiles of Enuresis among Primary School Children

References:

[1] Dhanidharka V. Primary nocturnal enuresis; where do we stand today? Indian Paediatrics. 2000; 37: 135-40.

[2] Gur E, Turhan P, Can G, Akkus S, Sever L, Guzelo S, et al. Enuresis; prevalence, Risk Factors, and Urinary pathology among school Children in Istanbul, Turkey; Paediatric International, Blackwell Publishers, Feb. 2004. 46(1):58-63(6).

[3] Akinyanju O, Agbato O, Ogunmekan AO, Okoye JU. Enuresis in sickle cell disease: prevalence studies. Journal of Tropical Paediatrics 1989; 35: 24-6.

[4] Winberg J, Bergstrom T, Jacobson B. Morbidity, age and sex distribution, recurrences, and renal scarring in symptomatic urinary tract infection in childhood. Kidney International (supplement) 1975; 4:101-6.

[5] American Psychiatric Association. Diagnosis and Statistical manual of Mental Diseases. (DSM-IV) Fourth Edition. Text Revision. Washington, DC.

[6] Lee SD, Sohn DW, Lee JZ, Park NC, Chung MK. An epidemiological study of Enuresis in Korean children. British Journal of Urology International, 2000; 85; (7):869-73.

[7] Yeung CK, Sreedhar B, Sihoe JY, Sit FY, Lau J. Differences in characteristics of nocturnal enuresis between children and adolescents, a critical appraisal from a large epidemiological study. British Journal of Urology International 2006; 97: 1069–73.

[8] Hagglof B, Andren O, Bergstrom E, Marklund L, Wendelius M. Self-esteem in children with nocturnal enuresis and urinary incontinence: improvement of self-esteem after treatment. European Urology 1998; 33 Supplement 3: 16–9.

[9] Mark SD, Frank JD. Nocturnal enuresis. British Journal of Urology. 1995:75:427-434.

[10] Butler R.J. Impact of nocturnal enuresis on children and young people. Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. 2001:35(3):169-76.

[11] Enuresis-Psychology. Wikipedia.

http://psychology.wikia.com.

[12] Glicklich L. An historical account of enuresis. American Academy of Paediatrics. 1951; (8):859-870.

[13] Hazza I, Tarawneh H. Primary Nocturnal Enuresis among School children in Jordan. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation, 2002; 13: 478-480.

[14] Gurnus B, Vurgun N, Lekili M, Iscan A, Muezzinoglu T, Buyuksu C. Prevalence of nocturnal enuresis and accompanying factors in children aged 7-11 Years in Turkey. Acta Paediatric 1999; 88: (12): 1369-72. www.springerlink.com.

[15] Chang P, Chen WJ, Tsai WY, Chiu YN. An epidemiological study of nocturnal Enuresis in Taiwaneese children. British Journal of Urology International, 2001; 87:678-681.

[16] Bower WF, Moore KH, Shepherd RB, Adams RD. The epidemiology of childhood enuresis in Australia. British Journal of Urology. 1996; 78:602-6.

[17] Spee Van der Wekke J. Childhood Nocturnal Enuresis in the Netherlands. Urology international. 1998; 51: 1022-6.

[18] Chiozza MI, Bernardinelli L, Calone P. An Italian epidemiological multicentre study of nocturnal enuresis. British journal of urology. 1998; 81: 86-9.

[19] Rodriquez Fernandez LM, Marugan de Migulsanz JM, Lapena Lopez de Armentia S. Epidemiological study of nocturnal enuresis: analysis of associated factors. An esp. paediatrics. 1997; 46: 252-8.

[20] Hanafin S. Socio demographic factors associated with nocturnal enuresis. British journal of Nurses. 1998; 7; 403-8.

[21] Thiedke C. Nocturnal Enuresis. American Family Physician. 2003Apr; 67(7); 1509-10.

[22] Eapen V, Mabrouk A.M. Prevalence and correlates of nocturnal enuresis in United Arab Emirates. Saudi Medical Journal, 2003; Vol (24); 49-51.

[23] Butler RJ, Golding J, Northstone K. Nocturnal enuresis at 7.5 yrs old; prevalence and analysis of clinical signs. British Journal Urology International. 2005; 96:404-410.

[24] Dahl N. Arnell H, Hjalmas K, Jagervall M, Lackgren G, Stenberg A et, al. Primary nocturnal enuresis: linkage to chromosome 12q and evidence for genetic heterogeneity. American Journal of human Genetics. 1995;57.

[25] Eiberg H, Berendt I. Mohr, J. Assignment of dominant inherited nocturnal enuresis (ENUR1) to chromosome 13q. Nature & Genetics. 10: 354-356, 1995.

[26] Von Gontard A, Schaumburg H, Hollmann E, Eiberg H, Rittig S. The genetics of enuresis: A review. Journal of Urology, 2001; 166:2438-43.

[27] Arnell H, Hjalmas K. Jegard M, Lackgren G, Sternberg A, Bengtsson B, et, al. The genetics of primary nocturnal enuresis: Inheritance and suggestions of a second major gene on Chromosome 12q. Journal of medical genetics, 1997; 34: 360-315.

[28] Robert M, Averous M, Besset A, Carlander, B, Billiard M, Guiter J, Grasset D. Sleep polygraph studies using cystometry in twenty patients with enuresis. European Urology, 1993; 24(1), 97-102.

[29] Mayo ME, Burns MW. Urodynamic studies in children who wet. British Journal of Urology. 1990; 65:641-5.

[30] Marc C. Primary nocturnal enuresis: current concepts. American Family Physician 1999; 59: 1205-14, 1219-20.

[31] Rushton, H. Wetting, and functional voiding disorders. Urologic Clinics of North America, 1995 22(1), 75-93.

[32] Norgaard JP, Hansen JH, Nielsen JB, Rittig S, & Djurhuus JC. Nocturnal studies in enuretics, a Polygraphic study of sleep-EEG and bladder activity. Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology, 1989a; 125: 73-78.

[33] Wille S, Nocturnal enuresis: Sleep disturbance and behaviour patterns. Acta Paediatric, 1994; 83(7): 772-4.

[34] Mikkelson EJ, Rapoport JL. Enuresis: Psychopathology, sleep stage, and drug response. Urologic Clinics of North America, 1980; 7(2): 361-77.www.dryatnight.com.

[35] Kalo BB, Bella H. Enuresis: prevalence and associated factors among primary school children in Saudi Arabia. Acta Paediatric. 1996; 85:1217-22.

[36] Saddock BJ, Saddock VA. Kaplan & Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry. 8th Edition. 1998; 1274-81. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. New York.

[37] Brown M., Jacobs M, & Pelayo R. Adult obstructive sleep apnoea with secondary enuresis. Western Journal of Medicine, 1995; 163(5): 478-480.

[38] Weider DJ, Sateia MJ, West RP. Nocturnal enuresis in children with upper airway obstruction. Otolaryngology. Head Neck Surgery. 1991; 105: 427-32.

[39] Norgaard JP, Jonler M, Rittig S, & Djurhuus, J.C. A pharmacodynamic Study of Desmopressin in patients with nocturnal enuresis. Journal of Urology, 1995; 153: 1984-86.

[40] Norgaard JP, Rittig S, & Djurhuus JC. Nocturnal enuresis: An approach to treatment based on pathogenesis. Journal of Paediatrics, pub, Anthony Jannetti Inc, 1998 Dec; 18(4):259-73.

[41] Omigbodun OO. Psychosocial issues in child and adolescent psychiatric clinic population in Nigeria. Social Psychiatry, Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2004; Aug; 39(8):667-72.

[42] Werry JS, Cohrssen J. Enuresis an aetiological and therapeutic study. Journal of Paediatrics, 1965; 67: 423-31.bjsw.oxfordjounals.org/cgi.

[43] Schmitt BD, Nocturnal enuresis. Australian Paediatrics. Rev, 1997; 6, Jun; 18(6):183-91.

[44] Butler, R.J. Childhood nocturnal enuresis: Developing a conceptual framework. Clinical psychology. Review: 2004; 24(8): 909-31.

[45] Esperanca M, Gerrard, JW. Nocturnal enuresis: Comparison of the effect of Imipramine and dietary restriction on bladder capacity. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 1969 Dec; 13; 101(12): 65-68. www.pubmedcentralnih.gov.

[46] Djurhuus JC. Definitions of subtypes of enuresis. Scandinavian Journal of Urology Nephrology Supplement. 1999; 202:5-7.

[47] Haque M, Ellerstein NS, Grundy JH, Shelov SP, Weiss JC, McIntire MS, et al. Parental perceptions of enuresis: A collaborative study. American Journal of Disease In childhood, 1981; 35(9): 809-11.

[48] Osungbade KO, Oshiname FO. Prevalence and perception of nocturnal enuresis in children of a rural community in southwestern Nigeria. Tropical Doctor. 2003 Oct; 33(4): 234-6.

[49] Araoye OM. Sample size determination. Research methodology with statistics for health and social sciences. Ilorin: Nathadex Publishers; 2003. p 115-22.

[50] Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brend I, Rao U, Ryan N. Kiddie-Sads, Present and lifetime version (KSADS-PL). Version 1.0 Pittsburgh: Department of psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine (UPMC) .1996. Retrieved from http://www.wpic.pitt.edu./ksads.

[51] Gureje O, Omigbodun OO, Gater R, Acha RA, Ikuwesan BA, Morris J. Psychiatric disorder in a paediatric primary care clinic. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1994; 165: 527-30.

[52] Azhir A, Frajzadegam Z, Adibi A, Hedayatpoor B, Fazel A, Divband A. An epidemiological Study of enuresis among primary school children in lsfahan, Iran. Published in Pub med. Saudi medical journal. 2006 Oct; 27(10); 1572-7.

[53] Etim U, Luka B. Girl Child Education Enrolment. World Bank Report, Oct; 2008.

Viewed PDF 1027 40 -

Perception and Knowledge of Cancer and Cancer Screening among Staff of Military Hospital LagosAuthor: Abiola Ajoke Odeleye OladiranDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.01.Art003

Perception and Knowledge of Cancer and Cancer Screening among Staff of Military Hospital LagosAuthor: Abiola Ajoke Odeleye OladiranDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.01.Art003Perception and Knowledge of Cancer and Cancer Screening among Staff of Military Hospital Lagos

Abstract:

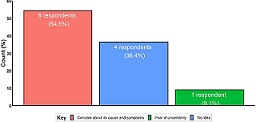

Perception and knowledge of cancer remain poor in developing countries. Problems associated with cancer incidence include late reporting due to fear, ignorance and financial constrains relating to cancer screening. This study sought to determine the perception and knowledge of cancer among health workers in Lagos. Method: A mixed-method study design comprising a qualitative study (Focus Group Discussions and In-depth Interview) and a quantitative study was employed to collect information from the staff of Military Hospital Lagos, southwest Nigeria. 30 Participants for the qualitative study were purposely recruited, while 200 participants for the quantitative study were selected using the proportional probability sampling technique after approval was received from the management of the hospital. Qualitative data was recorded using a recorder, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed thematically. Quantitative data was analyzed using SPSS 25.0 software at 95% CI, alpha set at 5%. Findings: The majority were women, 16(64.0%), with only 8(27%) of them under health insurance, with a minimum qualification of secondary school certificate, and mostly health attendants in the group discussion, while those in the interview group were all health professionals. The quantitative study revealed more males 106(53.0%), 73(36.5%) between 20-30 years, with 114(57.0%) married, over half, 122(61.0%) possessed a college degree, average income being >50-100 thousand naira monthly, 132(66.0%) respondents had health insurance. All cited fear and death sentence on hearing “cancer”, most had limited knowledge about cancer screening, only 5(2.5%) had any screening in the last 6 months.

Perception and Knowledge of Cancer and Cancer Screening among Staff of Military Hospital Lagos

References:

[1] Globocan 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012 v1.0. IARC CancerBase No. 11. ISBN-13, 978-92-832-2447-1.

[2] Harcourt N, Ghebre RG, Whembolua GL, Zhang Y, Osman SW, & Okuyemi KS. (2014). Factors associated with breast and cervical cancer screening behavior among African immigrant women in Minnesota. Journal of immigrant and minority health, 16(3), 450-456.

[3] Tapera O, Nyakabau A, Simango N, Guzha B, Jombo-Nyakuwa S, Takawira E, Mapanga A, Makosa D, & Madzima B. (2021). Gaps and opportunities for cervical cancer prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and care: evidence from midterm review of the Zimbabwe cervical Cancer prevention and control strategy (2016–2020). BMC Public Health. 21. 10.1186/s12889-021-11532-y.

[4] Silvera, S. A. N., Bandera, E. V., Jones, B. A., Kaplan, A. M., & Demisse, K. (2020). Knowledge of, and beliefs about, access to screening facilities and cervical cancer screening behaviors among low-income women in New Jersey. Cancer Causes & Control, 31(1), 43-49.

[5] Logan L. & Mcilfatrick S. (2011). Exploring women's knowledge, experiences, and perceptions of cervical cancer screening in an area of social deprivation. European Journal of Cancer Care20, 720–727. doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01254. x.

[6] Sheeran P, Harris PR, Epton T. (2014). Does a heightening risk appraisal change people’s intentions and behavior? A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Psychological bulletin, 140(2), 511–543. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033065.

[7] Adetona AE, Osungbade KO, Akinyemi OO, Obembe TA (2021). Uptake of Breast Screening Among Female Staff at A Tertiary Health Institution in South-West Nigeria. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Care - 3(2):17-30. Doi 10.14302/issn.2474-3585.jpmc-20-3557.

[8] Keah MM, Kombe Y, & Ngure K. (2020). Factors Influencing the Uptake of Cervical Cancer Screening among Female Doctors and Nurses in Kenyatta National Hospital. Journal of Cancer and Tumor International, 10(3), 31-38. https://doi.org/10.9734/jcti/2020/v10i330131.

[9] Odenusi AO, Oladoyin VO, Asuzu MC (2020). Uptake of cervical cancer screening services and its determinants between health and non-health workers in Ibadan, south-Western Nigeria. Afr. J. Med. Med. Sci. (4) 49, 573-5.

[10] Bukowska-Durawa A, & Luszczynska A. (2014). Cervical cancer screening and psychosocial barriers perceived by patients. A systematic review. Contemporary oncology (Poznan, Poland), 18(3), 153–159. https://doi.org/10.5114/wo.2014.43158.

[11] Bradley DT, Treanor C, McMullan C, et al. Reasons for non-participation in the Northern Ireland Bowel Cancer Screening Programme: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2015;5: e008266. doi:10.1136/ bmjopen-2015-008266.

[12] Marlow LAV, Waller J, & Wardle J. (2015). Barriers to cervical cancer screening among ethnic minority women: a qualitative study. The journal of family planning and reproductive health care, 41(4), 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc-2014-101082.

[13] Marlow LAV, Wardle J & Waller J. (2015). Understanding cervical screening non-attendance among ethnic minority women in England. Br J Cancer 2015;113(5):833–839. Doi:10.1038/bjc.2015.248.

[14] Chorley AJ, Marlow LAV, Forster AS, Haddrell JB & Waller J. (2016). Experiences of cervical screening and barriers to participation in the context of an organized program: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. Psycho-Oncology 26: 161–172. Doi: 10.1002/pon.4126.

[15] Wright KO, Faseru B, Kuyinu YA, Faduyile FA. (2011). Awareness and uptake of the Pap smear among market women in Lagos, Nigeria. J Public Health Afr; 2(e14): 58-62. https://doi.org/10.4081/jphia.2011.e14.

[16] Vrinten C, McGregor LM, Heinrich M, von Wagner C, Waller J, Wardle J, Black GB. (2017). What do people fear about cancer? A systematic review and meta-synthesis of cancer fears in the general population. Psycho-oncology 26(8):1070-1079. doi: 10.1002/pon.4287.

[17] Vrinten C, Waller J, von Wagner C, Wardle J. (2015). Cancer fear: facilitator and deterrent to participation in colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev; 24(2):400-5. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0967.

[18] Licqurish S, Phillipson L, Chiang P, Walker J, Walter F & Emery J. (2017). Cancer beliefs in ethnic minority populations: a review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. European journal of cancer care, 26(1), 10.1111/ecc.12556. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12556.

[19] Dim CC, Ekwe E, Madubuko T, Dim NR, Ezegwui HU. (2009). Improved awareness of Pap smear may not affect its use in Nigeria: a case study of female medical practitioners in Enugu, southeastern Nigeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 103(8): 852-854.

[20] Dim C C. (2012). Towards improving cervical cancer screening in Nigeria: A review of the basics of cervical neoplasm and cytology. Niger J Clin Pract 15:247-52.

https://www.njcponline.com/text.asp?2012/15/3/247/100615.

[21] Dim CC, Nwagha UI, Ezegwui HU & Dim NR. (2009). The need to incorporate routine cervical cancer counseling and screening in the management of women at the outpatient clinics in Nigeria, Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology; 29:8, 754-756, Doi: 10.3109/01443610903225323.

[22] Jensen LA, Allen MN. (1996). Meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Qual Health Res;6 (4):553–560. Doi:10.1177/10497323960060 040.

[23] Dharni N, Armstrong D, Chung-Faye G, & Wright AJ (2017). Factors influencing participation in colorectal cancer screening - a qualitative study in an ethnic and socio-economically diverse inner-city population. Health expectations: an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy, 20(4), 608–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12489.

[24] Hewitson P, Ward AM, Heneghan C, Halloran SP & Mant D. (2011). Primary care endorsement letter and a patient leaflet to improve participation in colorectal cancer screening: results of a factorial randomized trial. British journal of cancer, 105(4), 475–480. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.255.

Viewed PDF 1046 39 -

Quality of Tuberculosis Services in Lusaka, Zambia; Patients’ PerspectiveAuthor: Theresa Chansa Chilufya SikateyoDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.01.Art004

Quality of Tuberculosis Services in Lusaka, Zambia; Patients’ PerspectiveAuthor: Theresa Chansa Chilufya SikateyoDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.01.Art004Quality of Tuberculosis Services in Lusaka, Zambia; Patients’ Perspective

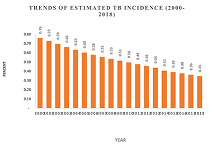

Abstract:

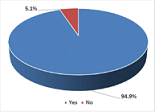

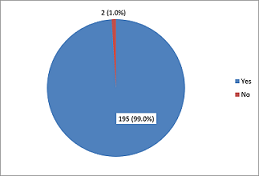

Zambia is among the 30 countries with high Tuberculosis (TB) burden, with an estimated 455 new cases per 100,000 people annually. Zambia and its partners are committed to accelerating the response to end TB through the provision of good quality of TB services, among other things. Despite the coordinated effort in addressing TB, little is documented about patients’ perceptions regarding the quality of TB services in Zambia. This study was conducted to assess the quality of TB services from the patient’s perspective. A facility-based cross-sectional study that utilized both quantitative and qualitative data collection. The study sample was 352 randomly selected patients on TB treatment and 58 purposefully selected TB treatment support persons. The patient’s perceived quality of care was measured by their perceived satisfaction of TB services in relation to accessibility of the TB clinic, timeliness of service provision, availability of qualified service providers, access to health education, the perceived attitude of service providers, and availability of drugs. Results revealed a high level of perceived good quality of TB services. The TB patients were more satisfied with the attitude of service providers, followed by the timeliness of service provision. Overall, 94.9% of the TB patients reported being satisfied with TB services. There is a high perception of good quality of TB services among the patients. Despite the high level of good quality, the study revealed limitations with regard to drug dispensation and the availability of qualified staff.

Quality of Tuberculosis Services in Lusaka, Zambia; Patients’ Perspective

References:

[1] Khatri, U. Davis, N., 2020. Quality of Tuberculosis Services Assessment in Ethiopia, Report. Measure Evaluation.

[2] Global tuberculosis report 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Moh (2015), The National Health Strategic Plan (NHSP) 2017-2021, Lusaka. Zambia.

[3] De Schacht, C., Mutaquiha, C., Faria, F., Castro, G., Manaca, N., Manhiça, I., and Cowan, J., 2019. Barriers to access and adherence to tuberculosis services, as perceived by patients: A qualitative study in Mozambique. PloS one, 14(7), p.e0219470.

[4] Colvin, C., De Silva, G., Garfin, C., Alva, S., Cloutier, S., Gaviola, D., Oyediran, K., Rodrigo, T. and Chauffour, J., 2019. Quality of TB services assessment: The unique contribution of patient and provider perspectives in identifying and addressing gaps in the quality of TB services. Journal of clinical tuberculosis and other mycobacterial diseases, 17, p.100117.

[5] NAC. 2019. Global Fund 2020-2022 Allocation Letter. Access online at: http://www.nac.org.zm/ccmzambia/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Zambia-2020-2022-allocation-letter-signed.pdf on15th December 2020.

[6] Bulage, L., Sekandi, J., Kigenyi, O. and Mupere, E., 2014. The quality of tuberculosis services in health care centres in a rural district in Uganda: the providers’ and clients’ perspective. Tuberculosis research and treatment, 2014.

[7] MoH (2015), Health Management Information System (HMIS), Lusaka. Zambia.

[8] MoH, (2018) The National Tuberculosis and leprosy Programme: TUBERCULOSIS Mannual, Lusaka Zambia. retrieved from https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/zambia_Tuberculosis.pdf on 21st May 2019.

[9] Bhatnagar, H. (2019). User-experience and patient satisfaction with quality of Tuberculosis care in India: A mixed methods literature review. Journal of Clinical https://doi.org/10/1016/j.jctube2019.100127 accessed online at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405579419300713 on 15th September 2020.

[10] Moore, Lynne PhD; Lavoie, André PhD; Bourgeois, Gilles MD; Lapointe, Jean MD Donabedian’s structure-process-outcome quality of care model, Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery: June 2015 - Volume 78 - Issue 6 - p 1168-1175 doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000663.

[11] WHO (2016) Health workforce requirements for universal health coverage and the sustainable development goals Human Resources for Health Observer Series No 17 accessed on https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250330/9789241511407-eng.pdf;sequence=1 on 20th October 2020.

[12] Dansereau, E., Masiye, F., Gakidou, E., Masters, S.H., Burstein, R. and Kumar, S., 2015. Patient satisfaction and perceived quality of care: evidence from a cross-sectional national exit survey of HIV and non-HIV service users in Zambia. BMJ Open, 5(12).

[13] Adhikary G, Shawon MSR, Ali MW, Shamsuzzaman M, Ahmed S, Shackelford KA, et al. (2018) Factors influencing patients’ satisfaction at different levels of health facilities in Bangladesh: Results from patient exit interviews. PLoS ONE 13(5): e0196643. Accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196643 on 15th September 2020.

[14] Charlotte, C. et al, (2019) Quality of TB services assessment: The Unique contribution of patient and provider perspectives in identifying and addressing gaps in the quality of TB services. Journal of Clinical Tuberculosis and other mycobacterial diseases, Vol 17, December 2019, 100117 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jctube.2019.100117.

[15] Costa-Sánchez, C. and Míguez-González, M.I., 2018. use of social media for health education and corporate communication of hospitals. El profesional de la información, 27(5).

[16] Arsenault, C. Roder-DeWan, S. and Kruk M.E Measuring and improving the quality of Tuberculosis care a framework and implications from the Lancet Global Health commission Journal of Clinical

Tuberculosis and other Mycobacterial diseases vol. 16, August 2019 100112 https://doi.org/10.1016/j/jctube.2019.100112 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405579419300531#bib0001.[17] WHO, (2015): The End Tuberculosis strategy, Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/Tuberculosis/strategy/end-Tuberculosis/en/ on 21st May 2019.

[18] Mergya Eticha, Belay & Atomsa, Alemayehu &, Birtukantsehaineh & Berheto, Tezera. (2014). Patients’ perspectives of the quality of tuberculosis treatment services in South Ethiopia. 3. 48-55. 10.11648/j.ajns.20140304.12.

[19] Aspler A, Menzies D, Oxlade O, Banda J, Mwenge L, Godfrey-Faussett P, Ayles H. Cost of tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment from the patient perspective in Lusaka, Zambia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008 Aug; 12(8):928-35. PMID: 18647453.

[20] Vaida Bankauskaite, Osmo Saarelma, why are people dissatisfied with medical care services in Lithuania? A qualitative study using responses to open-ended questions, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Volume 15, Issue 1, February 2003, Pages 23–029,

https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/15.1.23 accessed online at

https://academic.oup.com/intqhc/article/15/1/23/1797067 on 15th September 2020.

Viewed PDF 1094 41 -

Promoting Healthy Aging through Lifestyle Changes: The Plausibility and Evidence-based RecommendationsAuthor: Abiodun Bamidele AdelowoDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.01.Art005

Promoting Healthy Aging through Lifestyle Changes: The Plausibility and Evidence-based RecommendationsAuthor: Abiodun Bamidele AdelowoDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.01.Art005Promoting Healthy Aging through Lifestyle Changes: The Plausibility and Evidence-based Recommendations

Abstract:

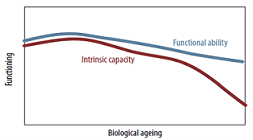

Through the advances in public health, most humans on earth are now assured to live to at least 60 years, regardless of their geographical location and socio-economic status. Between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the world’s population 60 years and above will be expected to increase from 900 million to 2.1 billion, while the average global life expectancy will be expected to increase by additional 10 years. Experts have ascribed this development as the most significant social transformation of the 21st century. However, although the world may have successfully learned how to live longer, it has not necessarily learned how to live healthier. In most situations, old age is associated with significant loss of physical and mental functionalities, increased risk of developing multiple diseases (including COVID-19), and reduced quality of life. This association has been described as the most important global public health challenge of the 21st century. The objective of this article is to investigate the scientific plausibility of slowing down the aging process and to identify evidence-based measures of achieving healthy aging. A review of related online free-full articles written in the English language published from 2000 to 2021 was done. It was noticed that the pace and quality of aging can be significantly influenced by controlling the lifestyle determinants of aging. Although the science of healthy aging is still evolving, there is enough evidence for healthcare professionals to recommend evidence-based strategies of achieving healthy aging to the public and to policymakers.

Promoting Healthy Aging through Lifestyle Changes: The Plausibility and Evidence-based Recommendations

References:

[1] Lange J., and Grossman S., 2021, Chapter Three: Theories of Aging. Jones &Bartlett Learning, 2021. Date of access: 15/2/2021. https://samples.jbpub.com/9781284104479/Chapter_3.pdf.

[2] Cabrera A.J.R., 2015, Theories of Human Aging of Molecules to Society. MOJ Immunol, 2(2), 00041. https://DOI:10.15406/moji.2015.02.00041.

[3] Garrido A, Cruces J, Ceprián N, Vara E, and de la Fuente M, 2019, Oxidative-Inflammatory Stress in Immune Cells from Adult Mice with Premature Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 20, 769. https://doi:10.3390/ijms20030769.

[4] Pathath A.W., 2017, Theories of Aging. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 4 (3), 15 – 22. https://DOI:10.25215/0403.142.

[5] Vin˜ J., Borra´ C., and Miquel J., 2007, Theories of Ageing. IUBMB Life, 59, 249–254.

[6] Miller J., 2011, The Fountain of Youth: The Quest for Biological Immortality, Date of access: 7/2/2021. http://www.slideshare.net/Justin2226/human-longevity-by-justin-miller.

[7] Belskya D.W, Caspic A., Houtsc R., Cohena H.J., Corcorane D.L, Danesef A., et al., 2015, Quantification of biological aging in young adults. PNAS, 4104 – 4110. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1506264112.

[8] Jia L., Zhang W., and Chen X., 2017. Common methods of biological age estimation. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 12, 759–772.

[9] European Commission (2020). European Study to Establish Biomarkers of Human Ageing: Calculating one’s biological age. Date of access: 6/5/2021. https://cordis.europa.eu/article/id/90427-calculating-ones-biological-age.

[10] Jiang S., and Guo Y., 2020, Epigenetic Clock: DNA Methylation in Aging. Stem Cells International, 2020, 1 – 9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/1047896.

[11] World Health Organization, 2011, Global Health and Aging, Date of access: 2/4/2021. https://www.who.int/ageing/publications/global_health.pdf.

[12] Barratt J., 2017. We are living longer than ever. But are we living better? Date of access: 4/6/2021. https://www.statnews.com/2017/02/14/living-longer-living-better-aging/.

[13] United Nations, 2017, World Population Ageing, Date of access: 7/7/2021. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2017_Highlights.pdf.

[14] World Health Organization, 2018, Ageing and health, Date of access: 17/2/2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health.

[15] Tabish S.A., 2012, Population aging is a global phenomenon, Date of access: 17/2/21. www.researchgate.net/publication/262915215_Population_aging_is_a_global_phenomenon.

[16] Khunti K., Singh A.K., Pareek M., and Hanif W., 2020, Is ethnicity linked to incidence or outcomes of covid-19? Preliminary signals must be explored urgently, BMJ, 369: 1 – 2. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.m1548.

[17] Beard J.R., Biggs S., Bloom D.E., Fried L.P., Hogan P., Kalache A., et al., 2012, Global Population Ageing: Peril or Promise, Geneva: World Economic Forum. Date of access: 15/5/2021. https://demographic-challenge.com/files/downloads/6c59e8722eec82f7ffa0f1158d0f4e59/ageingbook_010612.pdf.

[18] World Health Organization, 2017, Global strategy and action plan on ageing and health, Date of access: 2/4/2021. https://www.who.int/ageing/WHO-GSAP-2017.pdf.

[19] World Health Organization, 2017, WHO Clinical Consortium on Healthy Ageing. Topic focus: frailty and intrinsic capacity. Report of consortium meeting, Date of access: 3/6/2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272437/WHO-FWC-ALC-17.2-eng.pdf.

[20] World Health Organization, 2015, World report on ageing and health, Date of access: 1/3/2021.http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/186463/9789240694811_eng.pdf;jsessionid=FD0D4724D6073BBFC1CA52618828A755?sequence=1.

[21] Franklin B.A, and Cushman M., 2011, Recent Advances in Preventive Cardiology and Lifestyle Medicine. Circulation, 123, 2274 – 2283.

[22] Poulain M., Herm A., and Pes G., 2013, The Blue Zones: areas of exceptional longevity around the world. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 11, 87–108.

[23] Buettner D., and Skemp S., 2016, Blue Zones: Lessons from the World’s Longest Lived. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 318 – 321. https://DOI:10.1177/1559827616637066.

[24] Kadey M., 2020, Health Lessons from the World’s Blue Zones, Date of access: 20/10/2021. https://www.ideafit.com/personal-training/health-lessons-from-the-worlds-blue-zones/.

[25] Kim S., and Jazwinski S.M., 2015, Quantitative measures of healthy aging and biological age. Healthy Aging Res., 4, 1 – 25. http://doi:10.12715/har.2015.4.26.

[26] Batchelor F., Haralambous B., Lin X., Joosten M., Williams S., Malta S., et al., & 2016, Healthy ageing literature review: Final report to the Department of Health and Human Services. State of Victoria, Department of Health and Human Services, Date of access; 24/7/2021. https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/ageing-and-aged-care.

[27] Rudnickaa E., Napierałab P., Podfigurnab A., Męczekalskib B., Smolarczyka R., and Grymowicza M., 2020, The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas 139 (2020), 6–11.

[28] Whitbourne S.K., 2012, What’s Your True Age? You may be a lot younger than you think, CommonLit, 2014-2021, Date pf access: 13/7/2021. https://www.commonlit.org/texts/what-s-your-true-age.

[29] Jarreau P., 2019, How Old Are You, really? Meet Your Biological Age. Life Omic Health, 2020, Date of access: 18/5/2021. https://lifeapps.io/brain/how-old-are-you-really-meet-your-biological-age/.

[30] Elysium, 2020, What Is Your Biological Age? And Why Does It Matter? Date of access: 8/7/2021. https://www.elysiumhealth.com/en-us/science-101/biological-age.

[31] Glanz K., Rimer B.K., & Viswanath K., 2008, Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4th Edition, Date of access: 1/12/2021. https://iums.ac.ir/files/hshe-soh/files/beeduhe_0787996149(1).pdf.

[32] Terranova J., 2019, What’s Your Actual Age? Chronological vs. Biological Age, Thorne, 2019, Date of access: 4/9/2021. https://www.thorne.com/take-5-daily/article/what-s-your-actual-age-chronological-vs-biological-age.

[33] Lobachevsky University, 2020, Scientists have identified the role of chronic inflammation as the cause of accelerated aging, American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), 2021, Date of access: 8/8/2021. https://eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2020-01/lu-shi012920.php.

[34] Watson K., 2019, Everything You Need to Know About Premature Aging, Date of access: 24/11/2020. https://www.healthline.com/health/beauty-skin-care/premature-aging#tips-for-prevention.

[35] Basaraba S., 2020, How Lifestyle and Habits Affect Biological Aging, Date of access: 21/8/2021. https://www.verywellhealth.com/what-is-biological-age-2223375.

[36] Shields A., 2020, How to Calculate Your Biological Age, Date of access: 15/9/2021. https://dralexisshields.com/biological-age.

[37] Raman R., 2016. How to Safely Get Vitamin D From Sunlight. Date of access: 14/1/2022. https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/vitamin-d-from-sun.

Viewed PDF 1335 35 -

Conceptual Framework for Epidemics and Vaccination DilemmaAuthor: Odis Adaora IsabellaDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.01.Art006

Conceptual Framework for Epidemics and Vaccination DilemmaAuthor: Odis Adaora IsabellaDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.01.Art006Conceptual Framework for Epidemics and Vaccination Dilemma

Abstract:

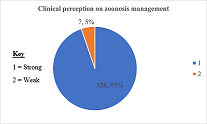

Outbreaks of diseases have positive and negative effects on humans. An example of the positive epidemic dilemma was seen in the 2020 lockdown across the world where families spent quality time together and couples seeking for the fruit of the womb conceived after many years, working from home was introduced, Lagosians working from home reduced stress from traffic, remote jobs were increased, online zoom, Webex webinars, online surveys, seminars, conference, Viva Voca, graduation and growth for online business and banking. Apps were available for the masses to access health online, known as Telemedicine. While the negative epidemics dilemma includes loss of jobs, slow down in economy across the world, poverty, drug abuse, self–medication, Anti-microbial resistance, child abuse, rape, divorce, shadow pandemic, death, and no access to education for those that do not have internet facilities to learn/study/school online. Vaccine’s hesitancy is an established dilemma that contributes to significant health challenges which cause a high rate of infant sickness and death. There are certain factors like cultural, social, demographic, and psychosocial factors that contribute to the vaccine dilemma. This conceptual framework illustrates the factors that drive epidemics and vaccine dilemma, which can be vaccination acceptance and hesitancy. For an intervention to be implemented successfully, we need to understand the triggers of epidemics and vaccination dilemma. The socio-demographic characteristics like age, sex, marital status, level of education, choice of hospital, employment status, level of income, health insurance status and the number of children is significantly associated with vaccine uptake among parents.

Conceptual Framework for Epidemics and Vaccination Dilemma

References:

[1] Osibogun (2014) “Emerging and Remerging diseases – Stopping the spread”: Lecture delivered at the Health Week ceremony of the University of Lagos.

[2] Vaccinate your family, 2019, “Vaccines are cost savings”, https://www.vaccinateyourfamily.org/why-vaccinate/vaccine-benefits/costs-of-disease-outbreaks/.

[3] De Figueiredo A et al. (2016) “Forecasted trends in vaccination coverage and correlations with socioeconomic factors: A global time-series analysis over 30 years”. Lancet Glob. Health, Vol 4, no. 10, pp., 726–735. pmid:27569362 View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar.

[4] Wessel L., (2017,) “Vaccine myths”. Science 2017; 356(6336):368–372. pmid:28450594 View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar.

[5] Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DM, Paterson P., (2014), “Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: A systematic review of published literature”, 2007-2012. Vaccine 2014; 32(19):2150–2159. PMID: 24598724 View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar.

[6] Black S, Rappuoli R., (2010), “A crisis of public confidence in vaccines”. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010; Vol. 2, no. 61, pp., 61. PMID: 21148125 View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar.

[7] Larson HJ., (2016) “Vaccine trust and the limits of information”. Science Vol. 353, no. 6305, pp., 1207–1208. PMID: 27634512 View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar.

[8] Holme P, Saramäki J. (2012) “Temporal networks”. Phys Rep; no. 519, pp., 97–125.

[9] Jansen VAA et al., (2003), “Measles outbreaks in a population with declining vaccine uptake”. Science Vol. 301, no. 5634, pp., 804. PMID: 12907792 View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar.

[10] Feh E, Fischbacher U., (2003), “The nature of human altruism”. Nature Vol., 2003; no. 425, pp., 785–791. View Article Google Scholar.

[11] Davis L., (1977), “Prisoners, paradox, and rationality”. Am PhilosQ,Vol. 14, no. 4, pp., 319–327.View Article Google Scholar.

[12] Sharma A, Menon SN, Sasidevan V, Sinha S (2019) “Epidemic prevalence information on social networks can mediate emergent collective outcomes in voluntary vaccine schemes”. PLoSComputBiolVol. 15, no. 5, e1006977. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006977.

[13] Verelst F, Willem L, Beutels P., (2016), “Behavioural change models for infectious diseasetransmission: a systematic review (2010-2015)”. J. R. Soc. Interface 2016; 13(125):20160820. pmid: 28003528 View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar.

[14] Marien González Lorenzo A, Alessandra Piatti C, Liliana Coppola C, Maria Gramegna C, Vittorio Demicheli D, Alessia Melegaro E, Marcello Tirani A, Elena Parmelli F.G, Francesco Auxilia A Lorenzo Moja A.B, the Vaccine Decision Group, 2015, Conceptual frameworks and key dimensions to support coverage decisions for vaccines, Volume 33, Issue 9, 25 February 2015, Pages 1206-1217, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.12.020.

[15] Saint-Victor DS, Omer SB., (2013), “Vaccine refusal and the endgame: Walking the last mile first”. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2013; 368(1623):20120148. PMID: 23798696 View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar.

[16] Bauch CT, Galvani AP, Earn DJD., (2003) “Group interest versus self-interest in smallpox vaccination policy”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 100, no.18, pp., 564–567. View Article Google Scholar.

[17] Bauch CT, Earn DJD., (2004) “Vaccination and the theory of games”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, Vol 101, no. 36, pp., 391–394. View Article Google Scholar.

[18] Zhang H-F, Wu Z-X, Tang M, La Y-C., (2014), “Effects of behavioral response and vaccination policy on epidemic spreading—an approach based on evolutionary-game dynamics”. Sci. Rep. 2014; 4:5666. pmid: 25011424 View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar.

[19] Verelst F, Willem L, Kessels R, Beutels P., (2018), “Individual decisions to vaccinate one’s child or oneself: A discrete choice experiment rejecting free-riding motives”. Soc. Sci. Med. Vol. 2018; no. 207, pp., 106–116. pmid: 29738898.

[20] Jolley D, Douglas KM., (2014), “The effects of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories on vaccination intentions”. PLoS ONE, Vol. 9, no. 2, pp., 89 - 177. pmid:24586574 View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar.

[21] Larson HJ, Ghinai I., (2011), “Lessons from polio eradication”. Nature; no. 473, pp., 446–447. pmid:21614056 View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar.

[22] Eubank S, et al., (2004), “Modelling disease outbreaks in realistic urban social networks”. Nature, Vol. 429, no. 6988, pp., 180–184. pmid:15141212 View Article PubMed/NCBI Google Scholar.

[23] Moinet A, Pastor-Satorras R, Barrat Alain., (2018), “Effect of risk perception on epidemic spreading in temporal networks”. Phy. Rev. E 2018; 97(1):012313. View Article Google Scholar.

[24] Rizzo A, Frasca M, Porfiri M., (2014), “Effect of individual behavior on epidemic spreading in activity-driven networks”. Phy. Rev. E Vol. 90, no. 4, 042801. View Article Google Scholar.

[25] Massaro E, Bagnoli F., (2014), “Epidemic spreading and risk perception in multiplex networks: A self-organized percolation method”. Phy. Rev. E 2014; Vol. 90, no. 5, 052817. View Article Google Scholar.

[26] Oku, A., Oyo-Ita, A., Glenton, C. et al. Factors affecting the implementation of childhood vaccination communication strategies in Nigeria: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 17, 200 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4020-6.

[27] Harapan H, Wagner AL, Yufika A, Winardi W, Anwar S, Gan AK, et al. (2020) Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine in Southeast Asia: a cross-sectional study in Indonesia. Front Public Health. 8:381. DOI: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00381PubMed Abstract, CrossRef Full Text, Google Scholar.

[28] Wang J, Jing R, Lai X, Zhang H, Lyu Y, Knoll MD, et al. (2020) Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Vaccines. 8:482. DOI: 10.3390/vaccines8030482 PubMed Abstract, CrossRef Full Text, Google Scholar.

[29] Bell S, Clarke R, Mounier-Jack S, Walker JL, Paterson P. (2020) Parents’ and guardians’ views on the acceptability of a future COVID-19 vaccine: a multi-methods study in England. Vaccine. 38:7789–98. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.027 PubMed Abstract, CrossRef Full Text, Google Scholar.

[30] Reiter PL, Pennell ML, Katz ML. (2020) Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine. 38:6500–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.043PubMed Abstract, CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar.

[31] Guidry JPD, Laestadius LI, Vraga EK, Miller CA, Perrin PB, Burton CW, et al. (2021) Willingness to get the Covid-19 vaccine with and without emergency use authorization. Am J Infect Control. 49:137–42. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.11.018 PubMed Abstract, CrossRef Full Text, Google Scholar.

[32] Dror AA, Eisenbach N, Taiber S, Morozov NG, Mizrachi M, Zigron A, et al. (2020) Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol. 35:775–9. DOI: 10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y PubMed Abstract, CrossRef Full Text, Google Scholar.

[33] Goldman RD, Yan TD, Seiler M, Cotanda CP, Brown JC, Klein EJ, et al. (2020) Caregiver willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19: Cross-sectional survey. Vaccine. 38:7668–73. DOI: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.084 PubMed Abstract, CrossRef Full Text, Google Scholar.

[34] Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, Rabin K, et al. (2021). A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 27:225–8. DOI: 10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9 PubMed Abstract, CrossRef Full Text, Google Scholar.

[35] Salali GD, Uysal MS. (2020) COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is associated with beliefs on the origin of the novel coronavirus in the UK and Turkey. Psychol Med. 1−3. DOI: 10.1017/S0033291720004067 PubMed Abstract, CrossRef Full Text, Google Scholar.

[36] Su Z, Wen J, Abbas J, McDonnell D, Cheshmehzangi A, Li X, et al. (2020) A race for a better understanding of COVID-19 vaccine non-adopters. Brain Behav Immun Health. 9:100159. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2020.100159 PubMed Abstract, CrossRef Full Text, Google Scholar.

[37] Joshi, A., Kaur, M., Kaur, R., Grover, A., Nash, D., & El-Mohandes, A. (2021). Predictors of COVID-

19 Vaccine Acceptance, Intention, and Hesitancy: A Scoping Review. Frontiers in public health, 9, 698111. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.698111.Viewed PDF 2233 53 -

Assessment of Health Worker’s Pattern of Managing Severe Malaria in Children Under the Age of Five (0-5years) in Northwestern Nigeria - A Cross-Sectional Study of Hospitals in Kebbi StateAuthor: Manir Hassan JegaDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.01.Art007

Assessment of Health Worker’s Pattern of Managing Severe Malaria in Children Under the Age of Five (0-5years) in Northwestern Nigeria - A Cross-Sectional Study of Hospitals in Kebbi StateAuthor: Manir Hassan JegaDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.01.Art007Assessment of Health Worker’s Pattern of Managing Severe Malaria in Children Under the Age of Five (0-5years) in Northwestern Nigeria - A Cross-Sectional Study of Hospitals in Kebbi State

Abstract:

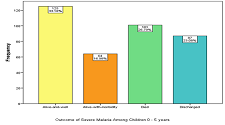

While severe malaria (SM) contributes to high mortality in children in Nigeria, appropriate treatment is cardinal in reducing SM death. However, there exist limited studies on how health workers (HWs) manage SM in children in Nigeria. The study aimed to assess the health worker’s treatment practices for severe malaria in children. A cross-sectional survey of severe malaria (SM) management in children (0- 5 years) was conducted in 377 participants across randomly selected 5 hospitals in Kebbi State. Data abstraction form was used to obtain parameters for SM from the patient’s record. A structured questionnaire was utilized to get information from HWs regarding the management of SM. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 23.0. A total of 377 cases of SM were identified. Documented symptoms for SM symptoms included fever (43.2 %), convulsion –seizure (26.3%), pallor (10.3%), and loss of consciousness (3.2%). All the cases (100%) were tested for malaria, with RDT being the commonest (60.2%) technique used, while 71 (18.83%) cases received intra-artesunate, 24 (6.36%) received intravenous quinine. 125 (33.16%) children fully recovered, with 87 (23.08%) discharge cases, and 41 (19.80%) received a follow-up dose of ACT. However, a mortality rate of 26.79% was observed. The pattern of managing severe malaria in this study resulted in improved quality of life in above half of the studied population. However, a higher rate is possible should health workers be given more on-the-job supervision. Besides, further study would be required to ascertain the source of knowledge of severe malaria management in the region.

Assessment of Health Worker’s Pattern of Managing Severe Malaria in Children Under the Age of Five (0-5years) in Northwestern Nigeria - A Cross-Sectional Study of Hospitals in Kebbi State

References:

[1] Bamiselu, O.F., Ajayi, I., Fawole, O. et al. Adherence to malaria diagnosis and treatment guidelines among healthcare workers in Ogun State, Nigeria. BMC Public Health 16, 828 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3495-x.

[2] World Health Organization. 2020. Malaria key facts. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria. Accessed on 1st January 2022.

[3] World Health Organization. (2015). World malaria report 2015. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/200018. Accessed 4th December 2021.

[4] WHO. The World malaria report at a glance. 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/world-malaria-report-2019. Accessed on 7th November 2021.

[5] Severe Malaria observatory. 2020. Severe Malaria Criteria, Features & Definition. https://www.severemalaria.org/severe-malaria/severe-malaria-criteria-features-definition. Accessed on 15th December 2021.

[6] White NJ. 2004. Review series Antimalarial drug resistance,. 2004;113(8).

https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI21682.

[7] Global Partnership to Roll Back Malaria. 2000. The African Summit on Roll Back Malaria, Abuja, Nigeria, April 25, 2000. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/67815.

[8] Kain KC, Harrington MA, Tennyson S, Keystone JS. Imported malaria: prospective analysis of problems in diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis. 1998 Jul;27(1): 142-9. doi: 10.1086/514616. PMID: 9675468.

[9] Mutsigiri-Murewanhema, Faith & Mafaune, Patron & Shambira, Gerald & Juru, Tsitsi & Bangure, Donewell & Mungati, More & Gombe, Notion & Tshimanga, Mufuta. 2017. Factors associated with severe malaria among children below ten years in Mutasa and Nyanga districts, Zimbabwe, 2014-2015. Pan African Medical Journal. 27. 23. 10.11604/pamj.2017.27.23.10957.

[10] Langhorne J, Ndungu FM, Sponaas A-M, Marsh K. Immunity to malaria: more questions than answers. Nat Immunol. 2008; 9:725 -32.DOI: https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0504.

[11] Kyei-Baafour E, Tornyigah B, Buade B, Bimi L, Oduro AR, Koram KA, Gyan BA, Kusi KA. 2020. Impact of an Irrigation Dam on the Transmission and Diversity of Plasmodium falciparum in a Seasonal Malaria Transmission Area of Northern Ghana Trop Med. 2020 Mar 19;2020:1386587. DOI: 10.1155/2020/1386587. eCollection 2020.PMID: 32308690.

[12] Dzeing-Ella A, Obiang PCN, Tchoua R, Planche T, Mboza B, Mbounja M.2005. Severe falciparum malaria in Gabonese children: clinical and laboratory features. Malar J. 2005(4). DOI: 10.1186/1475-2875-4-1.

[13] Edelu BO, Ndu IK, Igbokwe OO, Iloh ON. 2018. Severe falciparum malaria in children in Enugu, Southeast Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2018 Oct;21(10):1349-1355. DOI: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_140_18. PMID: 30297570.

[14] Okunola PO, Ibadin MO, Ofovwe GE, Ukoh G.2012. Co-existence of urinary tract infection and malaria among children under five years old: a report from Benin City, Nigeria. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2012 May;23(3):629-34. PMID: 22569460.

[15] Ukwaja KN, Aina OB, Talabi AA .2011. Clinical overlap between malaria and pneumonia: can malaria rapid diagnostic test play a role? J Infect Dev Ctries 5:199-203. doi: 10.3855/jidc.945.

[16] Shah, M.P., Briggs-Hagen, M., Chinkhumba, J. et al. Adherence to national guidelines for the diagnosis and management of severe malaria: a nationwide, cross-sectional survey in Malawi, 2012. Malar J 15, 369 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-016-1423-2.

[17] Achan J, Tibenderana J, Kyabayinze D, Mawejje H, Mugizi R, Mpeka B, et al. 2011. Case management of severe malaria–a forgotten practice: experiences from health facilities in Uganda. Plos one. 2011.DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone. 0017053.s006.

[18] Nwaneli EI, Eguonu I, Ebenebe JC, Osuorah CDI, Ofiaeli OC, Nri-Ezedi CA.2020. Malaria prevalence and its sociodemographic determinants in febrile children - a hospital-based study in a developing community in South-East Nigeria. Journal of preventive medicine and hygiene. 2020;61(2): E173-e80. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.15167%2F2421-4248%2Fjpmh2020.61.2.1350.

[19] Breman JG. The ears of the hippopotamus: manifestations, determinants, and estimates of the malaria burden. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001 Jan-Feb;64(1-2 Suppl):1-11. DOI: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.1. PMID: 11425172.

[20] Kwenti, T.E., Kwenti, T.D.B., Latz, A. et al. Epidemiological and clinical profile of paediatric malaria: a cross-sectional study performed on febrile children in five epidemiological strata of malaria in Cameroon. BMC Infect Dis 17, 499 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2587-2.

[21] WHO Guidelines for malaria, 16th February 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021 (WHO/UCN/GMP/2021.01). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/malaria/who-ucn-gmp-2021.01-eng.pdf.

[22] Wikipedia. Kebbi State from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kebbi_State. Accessed on 2nd October 2021.

[23] Bamgboye EA. 2013. Sample size determination in: Lecture notes on research methodology in the health and medical sciences. Ibadan. Folbam publishers. 2013:168-96.https://www.npmj.org/article.asp?issn=1117-1936;year=2020;volume=27;issue=2;spage=67;epage=75;aulast=Bolarinwa. Accessed on 17th September 2021.

[24] Batwala, V., Magnussen, P. & Nuwaha, F. 2010. Are rapid diagnostic tests more accurate in the diagnosis of plasmodium falciparum malaria compared to microscopy at rural health centres?. Malar J 9, 349 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-9-349.

[25] Orish, V.N., De-Gaulle, V.F. & Sanyaolu, A.O.2018. Interpreting rapid diagnostic test (RDT) for Plasmodium falciparum. BMC Res Notes 11, 850 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3967-4.

[26] Batwala, V., Magnussen, P. & Nuwaha, F. 2011. Comparative feasibility of implementing rapid diagnostic test and microscopy for parasitological diagnosis of malaria in Uganda. Malar J 10, 373 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-10-373.

[27] Neumann CG, Bwibo NO, Siekmann JH, McLean ED, Browdy B, Drorbaugh N. 2008. Comparison of blood smear microscopy to a rapid diagnostic test for in-vitro testing for P. falciparum malaria in Kenyan school children. East Afr Med J. 2008 Nov;85(11):544-9. doi: 10.4314/eamj. v85i11.9670.

[28] Endeshaw, T., Gebre, T., Ngondi, J. et al. 2008. Evaluation of light microscopy and rapid diagnostic test for the detection of malaria under operational field conditions: a household survey in Ethiopia. Malar J 7, 118 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-7-118.

[29] Wongsrichanalai C, Barcus MJ, Muth S, Sutamihardja A, Wernsdorfer WH. 2007. A review of malaria diagnostic tools: microscopy and rapid diagnostic test (RDT). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007 Dec;77(6 Suppl):119-27. PMID: 18165483.

[30] Manyando, C., Njunju, E.M., Chileshe, J. et al. 2014. Rapid diagnostic tests for malaria and health workers’ adherence to test results at health facilities in Zambia. Malar J 13, 166 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-13-166.

[31] Ayieko, P., Irimu, G., Ogero, M. et al.2019. Effect of enhancing audit and feedback on uptake of childhood pneumonia treatment policy in hospitals that are part of a clinical network: a cluster randomized trial. Implementation Sci 14, 20 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0868-4.

[32] Irimu G, Ogero M, Mbevi G, Agweyu A, Akech S, Julius T, et al. 2018. Approaching quality improvement at scale: a learning health system approach in Kenya. BMJ. 2018; 103:1013–9. DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciz844.

[33] Ampadu HH, Asante KP, Bosomprah S, Akakpo S, Hugo P, Gardarsdottir H, Leufkens HGM, Kajungu D, Dodoo ANO. 2019. Prescribing patterns and compliance with World Health Organization recommendations for the management of severe malaria: a modified cohort event monitoring study in public health facilities in Ghana and Uganda. Malar J. 2019 Feb 8;18(1):36. DOI: 10.1186/s12936-019-2670-9. PMID: 30736864; PMCID: PMC6368732.

[34] Dondorp A, Nosten F, Stepniewska K, Day N, White N;.2005. Southeast Asian Quinine Artesunate Malaria Trial (SEAQUAMAT) group. Artesunate versus quinine for treatment of severe falciparum malaria: a randomized trial. Lancet. 2;366(9487):717-25. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67176-0. PMID: 16125588.

Viewed PDF 1196 33 -

Drug Utilization Pattern of Antihypertensives in a Private Healthcare Setting in Enugu, NigeriaAuthor: Ngozi Dorathy UdemDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.01.Art008

Drug Utilization Pattern of Antihypertensives in a Private Healthcare Setting in Enugu, NigeriaAuthor: Ngozi Dorathy UdemDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.01.Art008Drug Utilization Pattern of Antihypertensives in a Private Healthcare Setting in Enugu, Nigeria

Abstract:

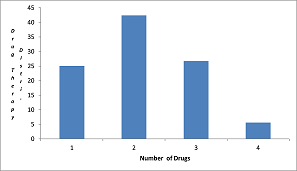

Hypertension is a public health challenge worldwide. Drug utilization study is a component of medical audit that monitors and evaluates prescribing practices and recommends necessary modifications. This study focused on the drug utilization pattern of antihypertensive drugs. The study was a retrospective study of facility records on drug use among hypertensive patients. It was conducted in a private health care setting facility in Enugu. A total of 1,005 prescriptions were evaluated for drug prescribing patterns. The blood pressure control was evaluated. A combination of two drugs was frequently prescribed (42.3%). Drug prescribing pattern showed that Angiotensin receptor blocker (Losartan) was mostly frequently prescribed (38.94%). Drug utilization of antihypertensive drugs was in agreement with JNC 7&8 recommendations. In the study combination of two or more anti-hypertensive drugs was frequently prescribed. The blood pressure control among the population was greater than 90%.

Drug Utilization Pattern of Antihypertensives in a Private Healthcare Setting in Enugu, Nigeria

References:

[1] World Health Organization (WHO). https://www.who.int. Accessed on 25/6/2021.

[2] World Health Organization 2013. Global health observatory (GHO) data.; https://www.who.int gho

Accessed on 20/9/2019.

[3] Oke O., Adedapo A. 2015, Antihypertensive drug utilization and blood pressure control in a Nigerian hypertensive population. Gen. Med.; 3 (2); DOI 10.4172/2327-5146.1000169.

[4] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2020. Facts about hypertension. https://www.cdc.gov blood pressure Accessed on 2/5/2021.

[5] Bosu W.K., Reilly S.T., Aheto J.M.K., Zuccelli E. 2016, Hypertension in older adults in Africa: Asystematic review and meta-analysis PLos ONE; 4(4): e0214934. DOI: 101371/journal.pone.0214934.

[6] Arodiwe E.B., Nwokediuko S.C., Ike S.O. 2014, Medical causes of death in a teaching hospital in South-Eastern Nigeria: A 16-year review. Niger J Clin Pract.; 17(6):711-6. DOI: 10.4103/1119-3077.144383.

[7] James A.P., Oparil S., Carter B. L.et al 2014, A 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the Panel Members Appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA .311(17):507- 520. DOI:10.100/jama2013.284427.

[8] Jarari N., Rao N., Peela R., Ellafi K.A., Shakila S., Said R.A., et al.2016, A review on prescribing patterns of antihypertensive drugs. Clin. Hypertension, 22:7, www.doi.org/10.1186/s40885-016-0042-0.

[9] Nachiya J.R.A.M., Parimalakrihnan S., Ramakrishna R.M. 2015, Study on drug utilization pattern of antihypertensive medications on out-patients and in-patients in a tertiary care teaching hospital: A cross sectional study. Afri, J of Pharm and Pharmacol.,9(11), 383-396. doi.10.5897/AJPP.2014.4263.

[10] Shah J., Balraj A. 2017, Drug utilization pattern of antihypertensive agents in patients of hypertensive nephropathy in a tertiary care teaching hospital; a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Basic Clin. Pharmacol., 6:2131-3. doi.10.18203/2319-2003.IJbcp20173636.

[11] AlavudeenSS, Alakhali KL, Ansari AS, Khan N. Prescribing pattern of anti-hypertensive drugs in diabetic patients of Southern Province Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Ars. Pharmaceutical., 56(2): 109-11.

[12] Mohan M. 2016, Drug utilization evaluation of antihypertensives in a super speciality hospital. Int. J of Pharma. Research & Review., 5(9):1-8.

[13] Amit S., Tanpreet K.B., Vishal G., Mahendra S.R., Manik C., Gaur A. 2018, Drug utilization study on hypertensive patients and assessment of medication adherence to JNC-8 Guidelines in North Indian tertiary care hospital: A cross-sectional study. Adv. Res. Gastroentero. Hepatol., 9 [1]: 555751. Doi. 10.19080/ARGH.2018.09.555751.

[14] Yadav K., Singh A., Sigdel M., Malla B., Guragain S., Aryal B., et al. 2015, Antihypertensive drugs utilization pattern in the clinic of a remote village of Nepal. Int. J. of Health Sciences and Research, 5(12):185-189.

[15] Jaiprakash H., Vinotini K., Vindiya., Vsalni., Vikneshwara, Vigneswaram et al.2013, Drug utilization study of antihypertensive drugs in a clinic in Malaysia. Int. J. of Basic and Clin Pharmacol., 2(4): 407-410.

[16] Sani M., Mijinyawa M., Adamu B., Abdu A., Borodo M. 2008, Blood Pressure control among treated hypertensives in a tertiary health institution. Nigeria J. Med., 17(3):270-274 Doi: 10.4314/njm.v.17i3.37394.PMID:18788251.

[17] Salako B.L., Ayodele O.E., Kadiri S., Arije A. 2002, Assessment of blood pressure control in a Black African population. Trop. Cardiol. 2002; 28(109):3-6.

[18] Mutnick A.H. 2004, Hypertension In: Leon S., Alam M., Sourney and Swanson L. ed, Comprehensive Pharmacy Review for NCLE. 5th edn., Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 762-767.

[19] Oparah C.2010, Pharmaceutical care in hypertension. In Opara C. ed Essentials of pharmaceutical care, 2nd edition Lagos: Cybex, 403.

[20] Adedapo D.A., Adedeji W.A., Adeosun A.M., Olaremi J., Okunlola C.K.2016, Antihypertensive drug use and blood pressure control among in-patients with hypertension in Nigeria tertiary health centre. Int. J. of Basic and Clin.Pharmacol., 5(3): 696-701. doi.org/10.18203/2319-2003IJPC20161503.

Viewed PDF 1043 26 -

Assessing the Relationship between Individual Level Dietary Intake and the Occurrence of Preeclampsia/Eclampsia and Haemorrhage among Pregnant Women in Eastern Region of Ghana: A Prospective Cohort StudyAuthor: James Atampiiga AvokaDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.01.Art009

Assessing the Relationship between Individual Level Dietary Intake and the Occurrence of Preeclampsia/Eclampsia and Haemorrhage among Pregnant Women in Eastern Region of Ghana: A Prospective Cohort StudyAuthor: James Atampiiga AvokaDOI: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.01.Art009Assessing the Relationship between Individual Level Dietary Intake and the Occurrence of Preeclampsia/Eclampsia and Haemorrhage among Pregnant Women in Eastern Region of Ghana: A Prospective Cohort Study

Abstract:

Pre-eclampsia/eclampsia (PE-E) and haemorrhage are dangerous diseases that occur in pregnancy. This study seeks to assess the relationship between individual-level dietary intake and the occurrence of pre-eclampsia/eclampsia and haemorrhage among pregnant women in the Eastern Region of Ghana. The prospective cohort study involved all pregnant women in their third trimester of pregnancy (>28 weeks gestational age) reporting for antenatal care (ANC) in seven Hospitals in the Eastern Region of Ghana. The study used a 24-hour repeated dietary recall to elicit dietary intake information from pregnant women until delivery. The majority of pregnant women in this study had adequate consumption of phosphorus far above the RDI, coupled with an inadequate intake of calcium, excess intake of sodium, and manganese. The average dietary intake for carbohydrates in this study was rather higher than the RDA. There was a statistically significant association between PE-E and the intake of vitamin C. A statistically significant association exists between the intake of calcium and vitamin A and haemorrhage. The findings show that pregnant women who consumed adequate and excess amounts of vitamin C reduced their odds of developing PE-E by 41.7% and 39.8%, respectively. The results show that pregnant women who had an excess intake of calcium were 6.128 times the odds of developing haemorrhage compared to those who had inadequate intake. Again, pregnant women who had adequate intake of vitamin A were 4.351 times the odds of developing haemorrhage compared to those who had inadequate intake. It is recommended that more nutrition specialists to be trained and posted to counsel pregnant women on nutrition in pregnancy to avert the consequences of PE-E and haemorrhage.

Assessing the Relationship between Individual Level Dietary Intake and the Occurrence of Preeclampsia/Eclampsia and Haemorrhage among Pregnant Women in Eastern Region of Ghana: A Prospective Cohort Study

References:

[1] World Health Organization. (2018). WHO recommendations: policy of interventionist versus expectant management of severe pre-eclampsia before term.

[2] Say, L., Chou, D., Gemmill, A., Tunçalp, Ö., Moller, A. B., Daniels, J., Gülmezoglu, A. M., Temmerman, M., & Alkema, L. (2014). Global causes of maternal death: A WHO systematic analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 2(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X.

[3] Peraçoli et al. (2020). Pre-eclampsia / Eclampsia. 318–332.