Plasmodium Falciparum and Schistosoma Heamatobium Infections in Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Clinic in Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis Western Region Ghana

Abstract:

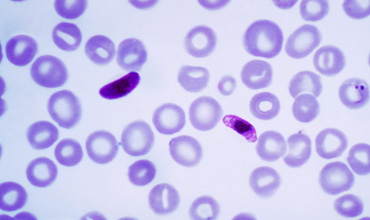

Plasmodium

falciparum and Schistosoma hematobium infections are very common parasitic

infections that affect pregnant women in the tropics. In this study we

evaluated the prevalence and contribution to anemia of Plasmodium falciparum and

Schistosoma heamatobium among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in Sekondi

Takoradi Metropolis.

This is across sectional

study involving pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in Effia nkwanta

regional hospital, Esikado hospital, Takoradi hospital and Jemima Crentsil hospital.

Plasmodium falciparum detection and hemoglobin estimation were done from blood

samples collected. Urine microscopy was done using the wet mount technique to detect

the presence or absence of Schistosoma heamatobium

A total of 872

pregnant women were sampled, 23.4% (204/872)were infected with plasmodium

falciparum infection, 3.3% (29/872) were infected with Schistosoma heamatobium

infection and 34.2% (298/872) were anemic. Plasmodium falciparum infection had

a significant association with anemia 32.2% (96/298)(P<0.001), Schistosoma

heamatobium infection had no significant association with anemia, 4.4% (6/298)

(p=0.3)

Plasmodium falciparum infection was higher and

contributes more to anemia in pregnant women than Schistosoma heamatobium

infection in this study. However it is very important to screen pregnant women for

other parasitic diseases with lower prevalence than malaria to evaluate their

burden and contribution to morbidity in pregnancy.

References:

[1].Artavanis‐Tsakonas,

K., Tongren, J. E., & Riley, E. M. (2003). The war between the malaria parasite

and the immune system: immunity, immunoregulation and immunopathology. Clinical & Experimental Immunology, 133(2), 145-152.

[2].Adegnika, A. A., Ramharter, M., Agnandji,

S. T., AtebaNgoa, U., Issifou, S., Yazdanbahksh, M., & Kremsner, P. G. (2010).

Epidemiology of parasitic co‐infections during pregnancy in Lambaréné, Gabon. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 15(10), 1204-1209.

[3].Brooker, S. (2007). Spatial epidemiology

of human schistosomiasis in Africa: risk models, transmission dynamics and control. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical

Medicine and Hygiene, 101(1),

1-8.

[4].Beeson, J. G., Brown, G. V., Molyneux,

M. E., Mhango, C., Dzinjalamala, F., & Rogerson, S. J. (1999). Plasmodium falciparum

isolates from infected pregnant women and children are associated with distinct

adhesive and antigenic properties. Journal

of infectious diseases, 180(2),

464-472.

[5].Bhaskaram, P., Balakrishna, N., Radhakrishna,

K. V., & Krishnaswamy, K. (2003). Validation of hemoglobin estimation using

Hemocue. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 70(1), 25-28.

[6].Clerk, C.A., Bruce, J., Greenwood, B. & Chandramohan, D. 2009. The epidemiology of malaria among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in an area with intense and highly seasonal malaria transmission in northern Ghana. Trop Med Int Health. 14(6):688-95.

[7].Chitsulo, L., Engels, D., Montresor, A.,

& Savioli, L. (2000). The global status of schistosomiasis and its control. Actatropica, 77(1), 41-51.

[8].DeMaeyer, E. M., Hallberg, L., Gurney,

J. M., Sood, S. K., Dallman, P., Srikantia, S. G., & World Health Organization.

(1989). Preventing and controlling iron deficiency anaemia through primary health

care: a guide for health administrators and programme managers.

[9].DATE, E. A. N. (2014). I hereby declare that this submission is

my own work towards the MPhil and that to the best of my knowledge, it contains

no material previously published by another person nor material which has been accepted

for the award of any other degree of the university, except where due acknowledgement

has been made in the text (Doctoral

dissertation, KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, KUMASI).

[10]. Friedman, J. F., Mital, P., Kanzaria,

H. K., Olds, G. R., & Kurtis, J. D. (2007). Schistosomiasis and pregnancy. Trends in parasitology, 23(4), 159-164.

[11]. Froeschke, G., Harf, R., Sommer, S.,

& Matthee, S. (2010). Effects of precipitation on parasite burden along a natural

climatic gradient in southern Africa–implications for possible shifts in infestation

patterns due to global changes. Oikos, 119(6), 1029-1039.

[12]. Gething, P. W., Patil, A. P., Smith,

D. L., Guerra, C. A., Elyazar, I. R., Johnston, G. L., … & Hay, S. I. (2011).

A new world malaria map: Plasmodium falciparum endemicity in 2010. Malaria journal, 10(1), 1.

[13]. Guyatt, H. L., & Snow, R. W. (2001).

The epidemiology and burden of Plasmodium falciparum-related anemia among pregnant

women in sub-Saharan Africa. The American

journal of tropical medicine and hygiene,

64(1 suppl), 36-44.

[14]. Greenwood, B., Marsh, K., & Snow,

R. (1991). Why do some African children develop severe malaria?. Parasitology today, 7(10), 277-281.

[15]. Guyatt, H. L. & Snow, R. W. (2004). Impact of malaria during pregnancy on low birth

weight in sub-Saharan Africa. Clin Microbiol

Rev. 17(4), 760-9. Review.

[16]. Gray, D. J., Ross, A. G., Li, Y. S.,

& McManus, D. P. (2011). Diagnosis and management of schistosomiasis. BMJ, 342(may16_2), d2651-d2651.

[17]. Ghana health service, (2005). Malaria

in Pregnancy Training manual for Health professionals.

[18]. Hotez, P. J., & Kamath, A. (2009).

Neglected tropical diseases in sub-saharan Africa: review of their prevalence, distribution,

and disease burden. PLoSNegl Trop Dis, 3(8), e412.

[19]. Orish, V. N., Onyeabor, O. S., Boampong,

J. N., Aforakwah, R., Nwaefuna, E., & Iriemenam, N. C. (2012). Adolescent pregnancy

and the risk of Plasmodium falciparum malaria and anaemia—A pilot study from Sekondi-Takoradi

metropolis, Ghana. Actatropica, 123(3), 244-248.

[20]. Pullan, R., & Brooker, S. (2008).

The health impact of polyparasitism in humans: are we under-estimating the burden

of parasitic diseases?. Parasitology, 135(07), 783-794.

[21]. Stevens, G. A., Finucane, M. M., De-Regil,

L. M., Paciorek, C. J., Flaxman, S. R., Branca, F., … & Nutrition Impact Model

Study Group. (2013). Global, regional, and national trends in haemoglobin concentration

and prevalence of total and severe anaemia in children and pregnant and non-pregnant

women for 1995–2011: a systematic analysis of population-representative data. The Lancet Global Health, 1(1), e16-e25.

[22]. Siegrist, D., & Siegrist-Obimpeh,

P. (1992). Schistosomahaematobium infection in pregnancy. Actatropica, 50(4), 317-321.

[23]. Tatem, A. J., Smith, D. L., Gething,

P. W., Kabaria, C. W., Snow, R. W., & Hay, S. I. (2010). Ranking of elimination

feasibility between malaria-endemic countries. The Lancet, 376(9752), 1579-1591.

[24]. Takougang, I., Meli, J., Fotso, S., Angwafo

3rd, F., Kamajeu, R., & Ndumbe, P. M. (2003). Hematuria and dysuria in the self-diagnosis

of urinary schistosomiasis among school-children in Northern Cameroon. African journal of health sciences, 11(3-4), 121-127.

[25]. Uneke, C. J. (2007). Impact of Placental Plasmodium falciparum Malaria on Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcome in

Sub-Saharan AfricaI: Introduction to Placental Malaria Yale. J Biol Med. 80(2), 39–50.

[26]. WHO. (2003). The africa malaria report.

Geneva (WHO/CDS/MAL/2003.1093).

[27]. Wilkins, H. A., Goll, P. H., Marshall,

T. D. C., & Moore, P. J. (1984). Dynamics of Schistosomahaematobium infection

in a Gambian community. I. The pattern of human infection in the study area. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical

Medicine and Hygiene, 78(2),

216-221.