Clinical Manifestations of Cryptococcal Meningitis in HIV Negative Patients-A Case Study

Abstract:

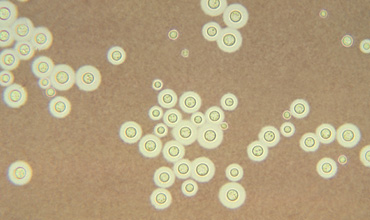

Cryptococcal Meningitis (CM) is a central nervous

system infection caused by a fungus. A large majority of cases are caused by

Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans. The fungus C. neoformans is found in

soil that contains bird droppings, particularly pigeon excreta, all over the

world. Cryptococcusneoformans var. gatti, on the other hand, is found primarily

in tropical and subtropical regions trees, most commonly eucalyptus trees. It

grows in the debris around the trees’ bases. Cryptococcal meningitis usually

occurs in people who have a compromised immune system and is a rare occurrence

in someone who has a normal immune system. Of the two fungi, Cryptococcalgattii

is the one more likely to infect someone with a normal immune system.The

incidence of infections caused by C.neoformans has risen markedly over the past

20 years as a result of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and increasing use of

immunosuppressive therapies. Cryptococcal meningitis is a common opportunistic

infection and an AIDS-defining illness in patients with late-stage HIV

infection, particularly in Southeast Asia and Southern and East Africa. It is

widely considered as the most common life-threatening AIDS related fungal

infection. Cryptococcal meningitis has been estimated at about 70 to 90%

worldwide in AIDS patients with mortalities of between 50% to 70% in

Sub-Saharan Africa. [2,3,4] Mortality from HIV-associated cryptococcal

meningitis remains high (13–33%), even in developed countries, because of the

inadequacy of current antifungal drugs and combinations, and the complication

of raised intracranial pressure.[2,7,8]In the cases presented, the findings

were so non-specific that the diagnosis was highly dependent on the CSF findings.

Based on the characteristics of the presenting signs and symptoms, Cryptococcal

meningitis should always be included in the differential diagnosis of chronic

or subacute meningoencephalitis, since clinical features are not specific.

References:

[1.] 2013-14

Zambia Demographic Health Survey

[2.] Abadi et

al. 1999

[3.] Casadevall

A (1998): Cryptococcus neoformans. Washington, DC: ASM Press, Perfect JR

[4.] Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention: C. gattii Infection Statistics (http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/cryptococcosis-gattii/statistics.html),

last updated May 2015.

[5.] Dr. Stephen

Berger (2015).Cryptococcosis: Global Status, By GIDEON Informatics, Inc.,

[6.] Dr. Peter

Mwaba (BSc.Hb.MBChB): The clinical and laboratory setting of cyptococcal

meningitis as seen at university teaching hospital, Lusaka and to evaluate

efficacy of fluconazole in its therapy, 1997.

[7.] French N,

Gray K, Watrea C et al. (2002) Cryptococcal infection in a cohort of

HIV-1-infected Ugandan adults. AIDS, 16, 1031–1038.

[8.] Geneva,

World Health Organization: Rapid advice: diagnosis, prevention and management

of cryptococcal disease in HIV infected adults, adolescents and children, 2013.

[9.] Holmes CB,

Losina E, Walensky RP, Yazdanpanah Y, Freedberg K :Review of human

immunodeficiency virus type 1-related opportunistic infections in Sub-Saharan

Africa, Clin Infect Dis, 36, 652–662. (2003)

[10.] John W

King, MD( 2014).Cryptococcosis

[11.] Kaplan JE,

Masur H, Holmes KK, USPHS, Infectious Diseases Society of America (2002)

Guidelines for Preventing Opportunistic Infections Among HIV-Infected Persons

2002. Recommendations of the U.S. Public Health Service and the Infectious

Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep, 51: 1–46.

[12.] Lalloo D,

Fisher D, Naraqi S, Laurenson I, Temu P, Sinha A, et al. Cryptococcal

meningitis (C. neoformans var. gattii) leading to blindness in previously

healthy Melanesian adults in Papua New Guinea. The Quarterly journal of

medicine. 1994 Jun;87(6):343-9.

[13.] Mwaba P.

Mwansa J, Chintu C et al. (2001) Clinical presentation, natural history, and

cumulative death rates of 230 adults with primary cryptococcal meningitis in

Zambian AIDS patients treated under local conditions. Postgrad Med J, 77,

769–773.

[14.] McCarthy

et al. 2006

[15.] Meiring et

al. 2012.

[16.] Meiring

ST, Quan VC, Cohen C, Dawood H, Karstaedt AS, McCarthy KM, Whitelaw AC,

Govender NP, Group for Enteric, Respiratory and Meningeal disease Surveillance

in South Africa (GERMS-SA) AIDS. 2012 Nov 28; 26(18):2307-14. [PubMed] A

comparison of cases of paediatric-onset and adult-onset cryptococcosis detected

through population-based surveillance, 2005-2007.

[17.] Robinson

PA, Bauer M, Leal ME et al. (1999) Early mycological treatment failure in

AIDS-associated cryptococcal meningitis. Clin Infect Dis, 28, 82–92.

[18.] Seaton RA,

Naraqi S, Wembri JP, Warrell DA (1996) Predictors of outcome in Cryptococcus

neoformans var. gattii meningitis. Q J Med, 89, 423–8.

[19.] Sarah S.

Long, Larry K. Pickering, Charles G. Prober: Principles and Practice of

Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 2012 (https://books.google.co.zm/books?isbn=1455739855)

[20.] Sloan D1,

Dlamini S, Paul N, Dedicoat M. Treatment of acute cryptococcal meningitis in

HIV infected adults, with an emphasis on resource-limited settings. [Cochrane

Database Syst Rev. 2008 Oct 8;(4):CD005647. doi:

10.1002/14651858.CD005647.pub2.

[21.] Tihana

Bicanic and Thomas S. Harrison: Cryptococcal meningitis. British Medical

Bulletin, (February, 2005).

[22.] The

Nigerian Journal of Medicine, Vol.19, No. 4 October - December 2010.

[23.] Thomas KE,

Hasbun R, Jekel J, Quagliarello VJ (2002). "The diagnostic accuracy of

Kernig's sign, Brudzinski's sign, and nuchal rigidity in adults with suspected

meningitis". Clin. Infect. Dis. 35 (1): 46–52. doi:10.1086/340979. PMID

12060874.

[24.] Yuanjie

Z1, Jianghan C, Nan X, Xiaojun W, Hai W, Wanqing L, Julin G. Cryptococcal

meningitis in immunocompetent children. Mycoses. 2012 Mar;55(2):168-71. doi:

10.1111/j.1439-0507.2011.02063.x. Epub 2011 Jul 18.