The Demographic and Clinical History as Predictors Contributing to the Prevalence of Caesarean Sections in Ghana: A Facility-Based Study

Abstract:

Caesarean section is an essential clinical obstetric intervention used to

reduce maternal and foetal death. Several indications contribute to the decision-making

to use CS as a delivery in the clinical environment. This study sought to determine

the prevalence of CS at LEKMA Hospital in Ghana and the demographic and clinical

history of mothers as predictors for the prevalence. Using a retrospective study

design, data for all mothers who had previously given birth at the hospital’s obstetric

and gynaecological department was used. Multiple logistic regression was applied

and a p-value<0.05 with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for results using IBM-SPSS

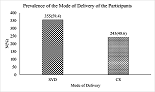

version 25. From the study, the prevalence of CS was 40.6% and the average age for

SVD and CS were 28.3±5.94years and CS 29.6±5.50years respectively.

The likelihood

of those aged 36 years and above undergoing CS was notably higher (AOR; 2.84, 95%CI

1.41-5.3, p-value <0.0001) compared to those aged 26-30 (AOR; 2.45, 95%CI 1.49-4.00,

p-value: 0.004) years and 31-35 (AOR; 1.65, 95% CI 0.94-2.90, p-value: 0.080) years.

The results further indicated that the risk of undergoing CS was greater among mothers with

parity of 1-2 (AOR: 1.56, 95%CI 1.02-2.41, p-value: 0.040). The prevalence of CS

in the study is greater than the recommended prevalence per 100 births by the World

Health Organization. The sociodemographic and clinical history of a pregnant woman

influenced the mode of delivery such that the increase in gestational age and parity

decreased the risk of CS. Whiles the educational status and age of the mothers at

the time of birth increased the risk of CS delivery.

References:

[1] Zewude B, Siraw G, Adem Y. The Preferences of Modes of

Child Delivery and Associated Factors Among Pregnant Women in Southern

Ethiopia. Pragmatic Obs Res. 2022; Volume 13(July):59–73.

[2] Apanga PA, Awoonor-Williams JK. Predictors of

caesarean section in northern Ghana: A case-control study. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;

29:1–11.

[3] Tsegaye H, Desalegne B, Wassihun B, Bante A, Fikadu K,

Debalkie M, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of caesarean section in

Addis Ababa hospitals, Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2019; 34:1–9.

[4] Shit S, Shifera A. Prevalence of cesarean section and

associated factor among women who give birth in the last one year at Butajira

General Hospital, Gurage Zone, SNNPR, Ethiopia, 2019. Int J Pregnancy Childbirth.

2020;6(1):16–21.

[5] Prah J, Kudom A, Afrifa A, Abdulai M, Sirikyi I, Abu

E. Caesarean section in a primary health facility in Ghana: Clinical

indications and. J Public Health Africa. 2017;8(639):98–102.

[6] Bi S, Zhang L, Chen J, Huang M, Huang L, Zeng S, et

al. Maternal age at first cesarean delivery related to adverse pregnancy

outcomes in a second cesarean delivery: a multicenter, historical,

cross-sectional cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):1–10.

[7] Seidu AA, Hagan JE, Agbemavi W, Ahinkorah BO, Nartey

EB, Budu E, et al. Not just numbers: Beyond counting caesarean deliveries to

understanding their determinants in Ghana using a population based

cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–10.

[8] Ghana Maternal Health Survey 2017. Vol. 13, Ekp. 2017.

1576–1580 p.

[9] Adu-Bonsaffoh K, Tamma E, Seffah J. Preferred mode of

childbirth among women attending antenatal clinic at a tertiary hospital in

Ghana: a cross-sectional study. Afr Health Sci. 2022;22(2):480–8.

[10] FAO. 3 : Promote gender equality and empower women 4 :

Reduce child mortality GOAL 5 : Improve maternal health Maternal mortality

remains unacceptably high across much of the developing world . Fully achieving

the MDG 5 target of reducing by three quarters the. Fact Sheet. 2015;5–6.

[11] WHO Statement on Caesarean Section Rates. World Heal

Organ. 2015;8.

[12] WHO. WHO non-clinical recommendations unnecessary to

reduce interventions caesarean sections. 2018.

[13] Hailegebreal S, Gilano G, Seboka BT, Ahmed MH, Simegn

AE, Tesfa GA, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of caesarian section in

Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis of the 2019 Ethiopia Mini Demographic Health

Survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2021;21(1):1–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-04266-7.

[14] Adewuyi EO, Auta A, Khanal V, Tapshak SJ, Zhao Y.

Cesarean delivery in Nigeria: Prevalence and associated factors •a

population-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6):1–12.

[15] Tarimo CS, Mahande MJ, Obure J. Prevalence and risk

factors for caesarean delivery following labor induction at a tertiary hospital

in North Tanzania: A retrospective cohort study (2000-2015). BMC Pregnancy

Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–8.

[16] Das P, Samad N, Sapkota A, Al-Banna H, A Rahman NA,

Ahmad R, et al. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Caesarean Delivery in

Nepal: Evidence from a Nationally Representative Sample. Cureus.

2021;13(12):11–2.

[17] Alhassan AR. Prevalence and socioeconomic predictive

factors of cesarean section delivery in Ghana. 2022;190–5.

[18] Gunn JKL, Ehiri JE, Jacobs ET, Ernst KC, Pettygrove S,

Center KE, et al. Prevalence of Caesarean sections in Enugu, southeast Nigeria:

Analysis of data from the Healthy Beginning Initiative. PLoS One.

2017;12(3):1–14.

[19] Genc S, Emeklioglu CN, Cingillioglu B, Akturk E, Ozkan

HT, Mihmanlı V. The effect of parity on obstetric and perinatal outcomes in

pregnancies at the age of 40 and above: a retrospective study. Croat Med J.

2021 Apr;62(2):130–6.

[20] Jahromi BN, Husseini Z. Pregnancy Outcome at Maternal

Age 40 and Older. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol

[Internet]. 2008;47(3):318–21. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S102845590860131X.

[21] Manyeh AK, Amu A, Akpakli DE, Williams J, Gyapong M.

Socioeconomic and demographic factors associated with caesarean section

delivery in Southern Ghana: evidence from INDEPTH Network member site.

2018;(November):1–9.

[22] Ahmed MS, Islam M, Jahan I, Shaon IF. Multilevel

analysis to identify the factors associated with caesarean section in

Bangladesh: evidence from a nationally representative survey. Int Health.

2022;1–7.

[23] Taye MG, Nega F, Belay MH, Kibret S, Fentie Y, Addis

WD, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with caesarean section in a

comprehensive specialized hospital of Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study; 2020.

Ann Med Surg [Internet]. 2021;67(May):102520. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102520.

[24] Sengoma JPS, Krantz G, Nzayirambaho M, Munyanshongore

C, Edvardsson K, Mogren I. Prevalence of pregnancy-related complications and

course of labour of surviving women who gave birth in selected health

facilities in Rwanda: A health facility-based, cross-sectional study. BMJ Open.

2017;7(7).

[25] Martinelli KG. The role of parity in the mode of

delivery in advanced maternal age women. 21(1):65–75.

[26] Patel RR, Peters TJ, Murphy DJ, Team S. Prenatal risk

factors for Caesarean section. Analyses of the ALSPAC cohort of 12 944 women in

England. 2005;(January):353–67.

[27] Lin L, Lu C, Chen W, Li C, Guo VY. Parity and the

risks of adverse birth outcomes: a retrospective study among Chinese.

2021;1–11.