Assessment of Health Worker’s Pattern of Managing Severe Malaria in Children Under the Age of Five (0-5years) in Northwestern Nigeria - A Cross-Sectional Study of Hospitals in Kebbi State

Abstract:

While severe malaria (SM) contributes

to high mortality in children in Nigeria, appropriate treatment is cardinal in reducing

SM death. However, there exist limited studies on how health workers (HWs) manage

SM in children in Nigeria. The study aimed to assess the health worker’s treatment

practices for severe malaria in children. A cross-sectional survey of severe malaria

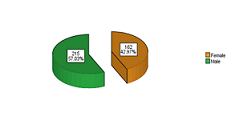

(SM) management in children (0- 5 years) was conducted in 377 participants across

randomly selected 5 hospitals in Kebbi State. Data abstraction form was used to

obtain parameters for SM from the patient’s record. A structured questionnaire was

utilized to get information from HWs regarding the management of SM. Statistical

analysis was done using SPSS version 23.0. A total of 377 cases of SM were identified.

Documented symptoms for SM symptoms included fever (43.2 %), convulsion –seizure

(26.3%), pallor (10.3%), and loss of consciousness (3.2%). All the cases (100%)

were tested for malaria, with RDT being the commonest (60.2%) technique used, while

71 (18.83%) cases received intra-artesunate, 24 (6.36%) received intravenous quinine.

125 (33.16%) children fully recovered, with 87 (23.08%) discharge cases, and 41

(19.80%) received a follow-up dose of ACT. However, a mortality rate of 26.79% was

observed. The pattern of managing severe malaria in this study resulted in improved

quality of life in above half of the studied population. However, a higher rate

is possible should health workers be given more on-the-job supervision. Besides,

further study would be required to ascertain the source of knowledge of severe malaria

management in the region.

References:

[1]

Bamiselu,

O.F., Ajayi, I., Fawole, O. et al. Adherence to malaria diagnosis and treatment

guidelines among healthcare workers in Ogun State, Nigeria. BMC Public Health

16, 828 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3495-x.

[2]

World

Health Organization. 2020. Malaria key facts. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria.

Accessed on 1st January 2022.

[3]

World

Health Organization. (2015). World malaria report 2015. World Health Organization.

https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/200018. Accessed 4th December 2021.

[4]

WHO.

The World malaria report at a glance. 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/world-malaria-report-2019.

Accessed on 7th November 2021.

[5]

Severe

Malaria observatory. 2020. Severe Malaria Criteria, Features & Definition. https://www.severemalaria.org/severe-malaria/severe-malaria-criteria-features-definition.

Accessed on 15th December 2021.

[6]

White

NJ. 2004. Review series Antimalarial drug resistance,. 2004;113(8).

https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI21682.

[7]

Global

Partnership to Roll Back Malaria. 2000. The African Summit on Roll Back Malaria,

Abuja, Nigeria, April 25, 2000. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/67815.

[8]

Kain

KC, Harrington MA, Tennyson S, Keystone JS. Imported malaria: prospective analysis

of problems in diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis. 1998 Jul;27(1):

142-9. doi: 10.1086/514616. PMID: 9675468.

[9]

Mutsigiri-Murewanhema,

Faith & Mafaune, Patron & Shambira, Gerald & Juru, Tsitsi & Bangure,

Donewell & Mungati, More & Gombe, Notion & Tshimanga, Mufuta. 2017.

Factors associated with severe malaria among children below ten years in Mutasa

and Nyanga districts, Zimbabwe, 2014-2015. Pan African Medical Journal. 27.

23. 10.11604/pamj.2017.27.23.10957.

[10]

Langhorne

J, Ndungu FM, Sponaas A-M, Marsh K. Immunity to malaria: more questions than answers.

Nat Immunol. 2008; 9:725 -32.DOI: https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0504.

[11]

Kyei-Baafour

E, Tornyigah B, Buade B, Bimi L, Oduro AR, Koram KA, Gyan BA, Kusi KA. 2020. Impact

of an Irrigation Dam on the Transmission and Diversity of Plasmodium falciparum

in a Seasonal Malaria Transmission Area of Northern Ghana Trop Med. 2020 Mar 19;2020:1386587.

DOI: 10.1155/2020/1386587. eCollection 2020.PMID: 32308690.

[12]

Dzeing-Ella

A, Obiang PCN, Tchoua R, Planche T, Mboza B, Mbounja M.2005. Severe falciparum malaria

in Gabonese children: clinical and laboratory features. Malar J. 2005(4). DOI: 10.1186/1475-2875-4-1.

[13]

Edelu

BO, Ndu IK, Igbokwe OO, Iloh ON. 2018. Severe falciparum malaria in children in

Enugu, Southeast Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2018 Oct;21(10):1349-1355. DOI: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_140_18.

PMID: 30297570.

[14]

Okunola

PO, Ibadin MO, Ofovwe GE, Ukoh G.2012. Co-existence of urinary tract infection and

malaria among children under five years old: a report from Benin City, Nigeria.

Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2012 May;23(3):629-34. PMID: 22569460.

[15]

Ukwaja

KN, Aina OB, Talabi AA .2011. Clinical overlap between malaria and pneumonia: can

malaria rapid diagnostic test play a role? J Infect Dev Ctries 5:199-203. doi: 10.3855/jidc.945.

[16]

Shah,

M.P., Briggs-Hagen, M., Chinkhumba, J. et al. Adherence to national guidelines for

the diagnosis and management of severe malaria: a nationwide, cross-sectional survey

in Malawi, 2012. Malar J 15, 369 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-016-1423-2.

[17]

Achan

J, Tibenderana J, Kyabayinze D, Mawejje H, Mugizi R, Mpeka B, et al. 2011. Case

management of severe malaria–a forgotten practice: experiences from health facilities

in Uganda. Plos one. 2011.DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone. 0017053.s006.

[18]

Nwaneli

EI, Eguonu I, Ebenebe JC, Osuorah CDI, Ofiaeli OC, Nri-Ezedi CA.2020. Malaria prevalence

and its sociodemographic determinants in febrile children - a hospital-based study

in a developing community in South-East Nigeria. Journal of preventive medicine

and hygiene. 2020;61(2): E173-e80. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.15167%2F2421-4248%2Fjpmh2020.61.2.1350.

[19]

Breman

JG. The ears of the hippopotamus: manifestations, determinants, and estimates of

the malaria burden. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001 Jan-Feb;64(1-2 Suppl):1-11. DOI: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.1.

PMID: 11425172.

[20]

Kwenti,

T.E., Kwenti, T.D.B., Latz, A. et al. Epidemiological and clinical profile of paediatric

malaria: a cross-sectional study performed on febrile children in five epidemiological

strata of malaria in Cameroon. BMC Infect Dis 17, 499 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2587-2.

[21]

WHO

Guidelines for malaria, 16th February 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization;

2021 (WHO/UCN/GMP/2021.01). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/malaria/who-ucn-gmp-2021.01-eng.pdf.

[22]

Wikipedia.

Kebbi State from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kebbi_State.

Accessed on 2nd October 2021.

[23]

Bamgboye

EA. 2013. Sample size determination in: Lecture notes on research methodology in

the health and medical sciences. Ibadan. Folbam publishers. 2013:168-96.https://www.npmj.org/article.asp?issn=1117-1936;year=2020;volume=27;issue=2;spage=67;epage=75;aulast=Bolarinwa.

Accessed on 17th September 2021.

[24]

Batwala,

V., Magnussen, P. & Nuwaha, F. 2010. Are rapid diagnostic tests more accurate

in the diagnosis of plasmodium falciparum malaria compared to microscopy at rural

health centres?. Malar J 9, 349 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-9-349.

[25]

Orish,

V.N., De-Gaulle, V.F. & Sanyaolu, A.O.2018. Interpreting rapid diagnostic test

(RDT) for Plasmodium falciparum. BMC Res Notes 11, 850 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3967-4.

[26]

Batwala,

V., Magnussen, P. & Nuwaha, F. 2011. Comparative feasibility of implementing

rapid diagnostic test and microscopy for parasitological diagnosis of malaria in

Uganda. Malar J 10, 373 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-10-373.

[27]

Neumann

CG, Bwibo NO, Siekmann JH, McLean ED, Browdy B, Drorbaugh N. 2008. Comparison of

blood smear microscopy to a rapid diagnostic test for in-vitro testing for P. falciparum

malaria in Kenyan school children. East Afr Med J. 2008 Nov;85(11):544-9. doi: 10.4314/eamj.

v85i11.9670.

[28]

Endeshaw,

T., Gebre, T., Ngondi, J. et al. 2008. Evaluation of light microscopy and rapid

diagnostic test for the detection of malaria under operational field conditions:

a household survey in Ethiopia. Malar J 7, 118 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-7-118.

[29]

Wongsrichanalai

C, Barcus MJ, Muth S, Sutamihardja A, Wernsdorfer WH. 2007. A review of malaria

diagnostic tools: microscopy and rapid diagnostic test (RDT). Am J Trop Med Hyg.

2007 Dec;77(6 Suppl):119-27. PMID: 18165483.

[30]

Manyando,

C., Njunju, E.M., Chileshe, J. et al. 2014. Rapid diagnostic tests for malaria and

health workers’ adherence to test results at health facilities in Zambia. Malar

J 13, 166 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-13-166.

[31]

Ayieko,

P., Irimu, G., Ogero, M. et al.2019. Effect of enhancing audit and feedback on uptake

of childhood pneumonia treatment policy in hospitals that are part of a clinical

network: a cluster randomized trial. Implementation Sci 14, 20 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0868-4.

[32]

Irimu

G, Ogero M, Mbevi G, Agweyu A, Akech S, Julius T, et al. 2018. Approaching quality

improvement at scale: a learning health system approach in Kenya. BMJ. 2018;

103:1013–9. DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciz844.

[33]

Ampadu

HH, Asante KP, Bosomprah S, Akakpo S, Hugo P, Gardarsdottir H, Leufkens HGM, Kajungu

D, Dodoo ANO. 2019. Prescribing patterns and compliance with World Health Organization

recommendations for the management of severe malaria: a modified cohort event monitoring

study in public health facilities in Ghana and Uganda. Malar J. 2019 Feb 8;18(1):36.

DOI: 10.1186/s12936-019-2670-9. PMID: 30736864; PMCID: PMC6368732.

[34]

Dondorp

A, Nosten F, Stepniewska K, Day N, White N;.2005. Southeast Asian Quinine Artesunate

Malaria Trial (SEAQUAMAT) group. Artesunate versus quinine for treatment of severe

falciparum malaria: a randomized trial. Lancet. 2;366(9487):717-25. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67176-0.

PMID: 16125588.