Effectiveness of Mobile Phone Reminders in Improving Adherence and Treatment Outcomes of Patients on Art in Adamawa State, Nigeria: A Ramdomized Controlled Trail

Abstract:

Adherence to antiretroviral therapy

(ART) among people living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLHIV) is very imperative

in achieving successful treatment outcome and decreased risk of HIV transmission

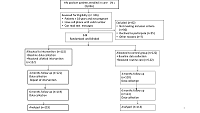

to uninfected people. This is a randomized controlled

trial study conducted in Adamawa State, Nigeria. 244 patients were randomized to

intervention or control group. Data

obtained from the study was analyzed using SPSS Version 21. Frequencies distributions,

descriptive statistics were presented, Inferential statistics such as Pearson Chi

square, McNemar’s test, Paired T test, correlation and repeated measures ANOVA were

used to measure the strength of associations and relationships between the various

variables and probability of statistically significant level set < 0.05 at 95%

Confidence interval. The response rates in the intervention and control groups were

99% and 96.7% at 3 months; 97.5% and 92.6% at 6 months, respectively. Individual

socio-demographic characteristics were not found to be associated with adherence

levels in this study. At six months follow up the proportion of the respondents

who had good adherence (>95%) was higher (89.1%) and statistically significant

(p= 0.001) in the intervention group compared to control group (63.1%) and (p= 0.617).

A significantly higher frequency in missed clinic appointments (7.98 vs 1.68) (p=0.024)

was noticed in the control group, and a statistically significant increase in the

proportion of participants who reported an increase in weight (p=0.001), CD4 cells

counts (p=0.001) and decrease in the presence of tuberculosis and other opportunistic

infections were observed among patients in the intervention group.

References:

[1]

Joint

United Nation Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS, 2018). Global HIV & AIDS statistics.

2018 fact sheet. http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet).

[3]

National

HIV Sero-prevalence Sentinel Survey (NHSS 2014).

[4]

Bekele

Belayihun1 and Rahma Negus (2015). Antiretroviral Treatment Adherence Rate and Associated

Factors among People Living with HIV in Dubti Hospital, Afar Regional State, East

Ethiopia. Hindawi Publishing Corporation International Scholarly Research Notices

Volume 2015, Article ID 187360, 5 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/187360.

[5]

World

Health Organization. (WHO, 2005) Interim WHO clinical staging of HIV/AIDS and HIV/AIDS

case definitions for surveillance: African region. Switzerland: https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/clinicalstaging.pdf.

[6]

Paterson

DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C, et al. (2002) Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in

patients with HIV infection. Annals of internal medicine. 2000;133(1):21–30. pmid:10877736.

[7]

Suleiman

IA, Momo A. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and its determinants among persons

living with HIV/AIDS in Bayelsa state, Nigeria. Pharmacy Practice 2016 Jan-Mar;14(1):631.

doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2016.01.631.

[8]

Kelley

LL' Engle, Kimberly Green MA, Stacey M Succop et al., (2015). Scaled-Up Mobile Phone Intervention for HIV Care and

Treatment: Protocol for a Facility Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc

2015;4(1): e11) doi:10.2196/resprot.3659 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4319075/.

[9] National Guideline

for HIV Prevention Treatment and Care (2016)- Nigeria. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s23252en/s23252en.pdf.

[10]

President

Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) (2016). Country/Regional Operational Plan

(COP/ROP) 2016 guidance. Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, Washington,

D.C.: OGAC;2015.

[11]

World

Health Organization (WHO, 2015). Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy

and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. Geneva: World Health Organization 2015

(http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/earlyrelease-arv/en.

[12]

Lemeshow

S, David W. Ho, J Klar, S K. Lwanga and World Health Organization (1990). Adequacy

of sample size in health studies. WHO IRIS: 239. http://www.who.int/irs/handle/10665/41607.accessed.

[13]

Olowookere,

S.A., Fatiregun, A.A, Ladipo, M.M.A, Abioye-Kuteyi, E.A. & Adewole, I.F. (2016).

Effects of adherence to antiretroviral therapy on body mass index, immunological

and virological status of Nigerians living with HIV/AIDS. Alexandria Journal of

Medicine (2016) 52, 51–54.

[14]

Anoje,

C., Agu, K.A., Oladele, E.A., Badru, T., Adedokun, O., Oqua, D., Khamofu, H., Adebayo,

O., Torpey, K., Chabikuli, O.N. (2017). Adherence to On-Time ART Drug Pick-Up and

Its Association with CD4 Changes and Clinical Outcomes Amongst HIV Infected Adults

on First-Line Antiretroviral Therapy in Nigerian Hospitals AIDS Behav. 2017 Feb;21(2):386-392.

doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1473-z.

[15]

Applebaum

AJ, Richardson MA, Brady SM, Brief DJ, keane TM (2009). Gender and Other psychosocial

factors as predictors of adherence to HAART in adults with comorbid HIV/aids, psychiatric

and substance related disorder. Aids Behav. ;13(1):60–5.

[16]

Carrieri

MP, Chesney MA, Spire B, et al. (1999).

Failure to maintain adherence to HAART in a cohort of French HIV-positive injecting

drug users. Int J Behav Med. 2003; 10:1–14.8. Holzemer WL, Corless IB, Nokes KM,

et al (2000). Predictors of self-reported adherence in persons living with HIV disease.

AIDS Patient Care STDS.13:185–97.9.

[17]

Bouhnik

AD, Chesney M, Carrieri P, et al. (2002)

Non adherence among HIV-infected injecting drug users: the impact of social instability.

J Acquire Immune Defic Syndr. ;31(suppl 3): S149 –S153.10.

[18]

Golin

CE, Liu H, Hays RD, et al. (2002). A prospective

study of predictors of adherence to combination antiretroviral medication. J Gen

InternMed. 2002; 17:756 – 65.11.

[19]

Gordillo

V, del Amo J, Soriano V, Gonzalez-Lahoz J. (1999) Socio demo-graphic and psychological

variables influencing adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS.13:1763–9.12.

[20]

Chesney,

M.A. (2000). Factors affecting adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Clinical Infectious

Disease 2000; 30 S171–S76.

[21]

Eldred

LJ, Wu AW, Chaisson RE, Moore RD (1998) Adherence to antiretroviral and pneumocystis

prophylaxis in HIV disease. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol.;

18:117–25.5.

[22] Moatti J.P, Carrieri

M.P, Spire B, Gastaut J.A, Cassuto J.P, Moreau J. (2000) Adherence to HAART in French

HIV-infected injecting drug users: the contribution of buprenorphine drug maintenance

treatment. The Manif 2000 study group. AIDS. 2000; 14:151–5.6.

[23]

Wagner,

G.J. (2002). Predictors of antiretroviral adherence as measured by self-report,

electronic monitoring, and medication diaries. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 16:599 –

608.

[24] Nduaguba, S.O., Soremekun, R.O., Olugbake, O.A., & Barner, J.C (2017).

The relationship between patient-related factors and medication adherence among

Nigerian patients taking highly active anti-retroviral therapy. Africa Health Science.

17(3): 738–745.

[25]

Bonolo,

P.F., Ceccato, M.B., Rocha, G. M., Acúrcio, F.A., Campos, L. N., & Guimarães,

M. C. (2013). Gender differences in non-adherence among Brazilian patients initiating

antiretroviral therapy. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 68, 612–620.

[26]

Simoni,

J.M., Pearson, C.R., Pantalone, D.W., et al.

(2006) Efficacy of interventions in improving highly active antiretroviral therapy

adherence and HIV-1 RNA viral load. A meta-analytic review of randomized controlled

trials. Journal Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 43(Suppl 1): S23–S35.

[27]

Wagner,

G.J, Kanouse, D.E., Golinelli, D., et al

(2006). Cognitive-behavioral intervention to enhance adherence to antiretroviral

therapy: a randomized controlled trial (CCTG 578) AIDS 20:1295–1302.

[28]

Carrico,

A.W, Antoni, M.H., Duran, R.E., et al.

(2006). Reductions in depressed mood and denial coping during cognitive behavioral

stress management with HIV-positive gay men treated with HAART. Annual Behavior

Medicine 31:155–164.

[29]

Pop-Eleches

C, Thirumurthy H, Habyarimana JP, Zivin JG, Goldstein MP, de Walque D, et al. (2011). Mobile phone technologies

improve adherence to antiretroviral treatment in a resource-

limited setting: a randomized controlled trial of text message reminders. AIDS.

2011;25(6):825–34. pmid:21252632.

[30]

Lester

RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, Kariri A, Karanja S, Chung MH, et al. (2010). Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral

treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomized trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9755):1838–45.

pmid:21071074 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61997-6].

[31]

Woods

SP, Moran LM, Carey CL, Dawson MS, Iudicello JE, et al. (2008) Prospective memory in HIV infection: is ‘‘remembering

to remember’’ a unique predictor of self-reported medication management? Arch Clin

Neuropsychology 23:257–270.

[32]

Chung

MH, Richardson BA, Tapia K, Benki-Nugent S, Kiarie JN, Simoni JM, et al. (2011). A randomized controlled trial

comparing the effects of counseling and alarm device on HAART adherence and virologic

outcomes. PLoS Medicine. 2011;8(3): e1000422. pmid:21390262.

[33]

Abdulrahman

SA, Rampal L, Ibrahim F, Radhakrishnan AP, Kadir Shahar H, Othman N (2017) Mobile

phone reminders and peer counseling improve adherence and treatment outcomes of

patients on ART in Malaysia: A randomized clinical trial. PLoS ONE 12(5): e0177698.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177698.

[34]

Kunutsor S, Walley J, Katabira E, Muchuro S, Balidawa

H, Namagala E, et al. Using mobile phones

to improve clinic attendance amongst an antiretroviral treatment cohort in rural

Uganda: A cross-sectional and prospective study. AIDS Behav. 2010; 14(6): 1347±1353.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9780-2 PMID:

20700644.

[35]

Sarna

A, Luchters S, Geibel S, Chersich MF, Munyao P, Kaai S, et al. Short-and long-term efficacy of modified directly observed antiretroviral

treatment in Mombasa, Kenya: a randomized trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;

48(5), 611±619. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181806bf1 PMID:18645509.

[36]

Rich

ML, Miller AC, Niyigena P, Franke MF, Niyonzima JB, Socci A, et al. (2012). Excellent Clinical Outcomes

and High Retention in Care among Adults in a Community-Based HIV Treatment Program

in Rural Rwanda J Acquire Immune Defic Syndr. 2012; 59(3): e35±e42. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824476c4

PMID: 22156912.

[37]

Mannheimer S, Friedland G, Matts J, Child C, Chesney

M. The consistency of adherence to antiretroviral therapy predicts biologic outcomes

for human immunodeficiency virus infected persons in clinical trials. Clin Infect

Dis. 2002; 34:1115–21.

[38]

El-Khatib

Z, Ekstrom AM, Coovadia A, Abrams EJ, Petzold M, et al. (2011) Adherence and virologic suppression during the first 24

weeks on antiretroviral therapy among women in Johannesburg, South Africa - a prospective

cohort study. BMC Public Health 11: 88.

[39]

Sampaio-Sa

M, Page-Shafer K, Bangsberg DR, et al.

100% adherence study: educational workshops vs video sessions to improve adherence

among ART-naive patients in Salvador, Brazil. AIDS Behaviour. 2008;12(4 Suppl):

S54–S62.

[40]

Garcia

R, Ponde M, Lima M, Souza AR, Stolze SM, Badaro R. Lack of effect of motivation

on the adherence of HIV-positive/AIDS patients to antiretroviral treatment. Braz

J Infect Dis. 2005;9(6):494–499.